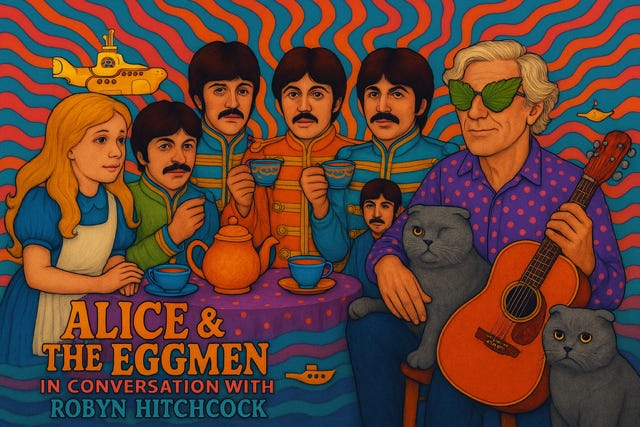

25 Interview Special: Robyn Hitchcock

Pop portals, psychedelia and Looking-Glass infused ‘Autumn Sunglasses’

“Lewis Carroll was part of the mental compost that certain minds grow out of”

Robyn Hitchcock

This week, it’s a real pleasure to share my interview with the great Robyn Hitchcock, a fan — it turns out — of both The Beatles and Lewis Carroll. We delve into his memoir ‘1967’, living in Nashville, and also portals, psychedelia and his song ‘Autumn Sunglasses’, which was influenced by a stay in the Isle of Wight, from where he was commuting back and forth - through a “looking-glass” — to Sydney.

Nick Coates: Robyn, thanks so much for speaking to me. To kick us off, can we talk about your tour? Is there anything new you're doing, or any places you're particularly excited about?

Robyn Hitchcock: Well, the tour is constant, really. I'm doing the usual Midwest run. In mid-July I’ll be taking my San Francisco-based group to Winnipeg Folk Festival: we're mixing up my ‘greatest flops’ with various totems of psychedelia, doing things like ‘See Emily Play’ and ‘Waterloo Sunset’, stuff by The Doors and Country Joe and the Fish, and all sorts of people. The biggest thing that we managed to do recently is ‘I Am the Walrus’ with the sampled strings in the middle. And I think we did a pretty good version!

I'm basically now at this advanced age where there's a part of me that’s simply playing the old songs I loved and grew up with. It’s all par for the course for people reaching a certain age and trying to get back where they came from, old people shuffling around trying to find the key, but always going to the wrong door. And yet that music has lasted. It's certainly lasted for its own generation, and I think it's also seeded itself in future generations, because it's the big bang from which came classic rock, which still dominates the world today.

NC: We’re here today to talk about the ‘60s, The Beatles and Lewis Carroll. But I've got some followers who are big fans of yours, and I thought it would be fun to start with some of their questions too…

First up is Heather from Seattle. She wrote to me about ‘Heliotrope’, which she loves because it’s a song about cats. And then I've seen on Patreon that the great Tubby is immortalized in a new song; you talked about him as your ‘psychic counsellor’, which I found striking and beautiful. What is your love of cats? What's going on there?

RH: Well, it developed very slowly. I actually wasn't very keen on cats at all, largely because I didn't like the smell of cat food, which is a very autistic response. But I gradually learned to ‘speak cats’. And now I'm a fully-fledged cat lover.

In ‘Heliotrope’ I'm conflating a person with a cat, like the goddess Bast. Cats are sort of unfathomable, because they they're a bit like the knight in chess: sort of two-steps forward and one sideways. Dogs are directional, like the bishop or the castle: “whoomph! Here I am!’. A cat’s more like “yeah, okay, sure…”. They seldom go in a direct line. If they're hungry, they'll go straight for the food, but you can’t generally put a cat somewhere and have it stay there. It will come back to where you've put it, but it'll do it its own way.

NC: OK let’s shift from cats to cheese. My friend Nick asks, “regarding the excellent ‘The Cheese Alarm’, how are Trump tariffs affecting Robyn's cheese consumption in terms of quantity, quality and variety?”

RH: I still get cheese. People give me exotic cheeses at gigs, if I'm lucky. I'm not bombarded with them, but I got a couple of nice ones in San Francisco last week. Right now, I think the tariffs are affecting me more psychologically than in terms of the cheese in my pocket, as it were.

NC: I'll let Nick know, thanks! Are there any particular favourites, though? I mean, you talked about Jarlsberg and Chaume, but what else?

RH: Well the one I didn't put in the song was Mimolette, which I really love. It's a kind of French cheese that masquerades as a Dutch one. It's the hardest cheese I've ever run across, and people on the cheese counter never look at you happily if you ask for a tranche of Mimolette. But it's fabulous stuff. It's sort of fatty and rich and designed for heartburn. But I've just been introduced to some new Californian cheeses, which are fabulous. And there's a lot of artisanal cheese floating around, if cheese can be said to float, in stores in Nashville. So we're not short of good stuff.

NC: What a relief! My wife has a different question, since you mentioned Nashville, which I think gets us into your book 1967, and questions of upbringing and influence. My sense, from reading the book today, is that it’s a Dylan connection, and that's what drew your attention to Nashville. Katherine wants to know how it feels now that you're living the dream, living in Nashville?

RH: Well, I have to remind myself that I am living the dream since, like all great dreams, it’s tinged with nightmare. You wouldn't necessarily choose to come and live in America right now and yet, walking around, going to the cafés and into the bars where there's always terrific music, there's no sign of anything amiss. You don't see the Gestapo or the mob tramping up and down; it seems absolutely like it was before. The sun shines and people groove - it’s lovely!

I first heard about Nashville because of Bob Dylan. As I say in the book, Dylan became the gateway to my future. Dylan was the pied piper that lured me into this completely unwittingly, and he lured 1000s of other young people, largely boys, down this path. Like tadpoles, a few of us actually got to do what we wanted to do originally. And I'm one of those lucky tadpoles. Dylan came here to make albums, and so I came here to make albums. I made one in 2004 with Gillian Welch and Dave Rawlings, so that's 20 years ago. And then I met Emma, my wife Emma, who's Australian, and she’d just moved here from Sydney, so we wound up living here. That's a condensed version of the story!

NC: I do want to go back to 1967 and your book which I found was a real page-turner, so easy to read, yet so vivid. I know you wrote it on your phone, which seems kind of amazing, really, but I think explains why it's so pithy.

RH: Maybe. I also revised it a lot. Almost constantly as I was writing it. And maybe that is easier to do if it's on a phone. But I also only use my index finger. I don't use the two thumbs like our ancestors used to when they were writing up in the trees.

NC: Another thing I loved about it was how evocative it was. For someone who didn’t board, but still went to several English public schools, I can relate to your description of the ‘English freak show’. And I loved the bit about Dylan seeming to know something you didn't know. There’s a lot going on.

RH: I just happened to be there at that extraordinary time when the world was going into colour and modern life began, when they put the doors on the toilets. Our generation came up just as conscription ended. There were these huge things that we just dodged, and then I got there, and what do you know, within two years, there was a whole load of people whose worldview was dominated by gatefold sleeve albums.

It was a really accelerated time. And I was also physically accelerating. It was the year that I grew eight inches. That can only happen to you once. And that occurred to me at the same time as the world was, culturally, growing eight inches.

Homosexuality was legalized in Britain, abortion was legalized. It became socially acceptable to have sex with people to whom you were not married. The pill, for ill or good, was coming into prominence for women. All the ‘armature’ of modern life developed around that time. And if you look at what the world was like in 1966 it was still a kind of black-and-white, everybody had pretty short hair, except for pop singers (who were still called ‘beatniks’). I sort of can't believe I happened to live then, and that I went through puberty at that very spot, with that music. No wonder I never really got away.

NC: So almost a kind of arrested development, maybe? Is that fair?

RH: I think it very much is in a way. Because I use it as a badge, people kind of let me get away with it, rather than saying, “you poor fucker, you just never grew up, did you?! Look at your wallpaper! Look at your posters!”

NC: 1967 is a crazy period in terms of my blog too, for Lewis Carroll, The Beatles and so much more. That really is the high point. In ‘68 you get the riots in Paris, things change. They cool very quickly. But one thing that I’m fascinated about in your work is the cultural amalgam. You say you love hymns like ‘He who would valiant be’, and ‘Jerusalem’, that they’re “as important to me as Strawberry Fields”. But there’s Dylan too. So maybe ‘67 was that point of alchemy where, you know, the Beatles’ very Englishness is fused with this incredible new sort of sound and American culture.

RH: I think that's a very good way of describing it, Nick! It was the point of alchemy, and Britain and America had been cross-pollinating musically for a few years. Rock’n’roll coming from America. And then Britain sending back the Beatles and The Rolling Stones and The Kinks. And then America coming up with Bob Dylan. And then The Byrds kind of merging The Beatles and Dylan.

What I've found with The Beatles is that there's always something to bring you back in. I loved them when I was 10, and I love them now, not just because I did love them then, but because I've spent my life being a musician. Beatle chords and Beatle chord structures are still fascinating; you can never get musicians to agree exactly on what's happening. It can sound fairly simple, but actually there's all these little eddies and undercurrents. It’s a bit trompe l’œil - it's never as simple as it seems.

And I think the great thing about Beatles music is that it's children's music. It appeals to the child in you, and that's why, hopefully Gen Zs, and whatever lies beyond, if anything does, will continue to pick up on it.

NC: I loved your definition of psychedelia being that when you look closer, things aren’t quite the same. There's something in the way you’ve just described The Beatles music that I think conforms to that: you go a bit closer and there are new things to see. What are some of your desert-island Beatle choices?

RH: I suppose I like the later stuff more. Of the early songs, I think Paul McCartney's ‘Things We Said Today’ is absolutely brilliant. I guess he wrote that pretty much by himself. That's a fantastic song.

NC: I’m a fan of that one too. It's those seventh chords, isn't it? And then when it goes into A major from the A minor. It's just that sense of a clearing or opening up. Is that right?

RH: Yes, and the bit where it drops. When he sings “love is here to stay, and that's enough” it goes from something like B to B flat to A minor. Really unlikely chords, but that's what they actually are. I also really like ‘Only A Northern Song’. We worked that out last week with its apparently almost random chords in the middle bit.

And I love ‘I Am the Walrus’. It’s my favourite of John's psychedelic-era songs. It's a much more successful recording than ‘Strawberry Fields’, which I think was a bit laboured. It's an iconic recording, but you can hear that they did splice two versions together. It feels a bit overworked. Whereas Walrus just feels like “Oh my God”. The way those chords go is extraordinary.

I also love ‘Because’ - that’s an extraordinary piece of music with that three-part harmony that’s double-tracked, or triple-tracked.

NC: Well, that takes me to one of my contentions about Lewis Carroll. It’s definitely not overt or deliberate, whereas there are times when they say that “this was us doing an Alice”. But ‘Because’ is, according to John, something like Moonlight Sonata turned on its head, he asked Yoko to play the chords backwards. So there's something I think that's interesting about these Lewis Carroll-like ‘moves’: turn it upside down, shrink it, mirror it, double it. I feel that with all of those experimental moves - the Lowrie organ, ADT, varispeed - that there is something Wonderland in their approach.

As someone who's made things using similar techniques, and listened to this music for so long, is that part of the magic?

RH: Well, the thing is, those were all effects that were all being used for the first time. Just as in Alice in Wonderland Alice hasn't experienced this before. Her second trip is going through the mirror, the first trip is going down the rabbit hole. If Alice had done, you know, 47 trips, she might have begun to get used to seeing these people. “Oh, look, it’s Tweedledee up on the branch with the Cheshire Cat!’. There’d be some familiarity.

When the Beatles were doing all those things like ADT and singing through a Leslie, it was happening for the first time. So what you've got with both Alice, with Lewis Carroll's writing, and the fabs, is that sense of exploration, that they're going into something new.

But it's the kind of thing that's presented as if it's for children. The Beatles a bit less so. Whereas Alice was technically a children's book, they didn't say, ‘here's a kind of gnomic brochure or guidebook to rewiring your mind. You are Alice. And these are your options’. It was actually ‘Okay, kids. Here's a little book for the under 10s’. And with The Beatles it was “okay, pop pickers, here's The Beatles’. Yeah. it wasn't really supposed to appeal to anyone over 15.

NC: I also loved you talking about ‘67 being a kind of portal into ‘no-rules’.

RH: Those were experimental times. We live in regressive times, unfortunately. There was so much momentum. And I always think of Yellow Submarine - the blue meanies counter-attacking. The blue meanies have been counter attacking, arguably, since 1968. There were obvious blue meanies like Margaret Thatcher. And they just seem to keep coming.

NC: I was keen to chat to you because of the Lewis Carroll thing, and I'm keen to understand its relationship with your work. One in two critics is going to accuse you of being ‘a Lewis Carroll person’. But it feels to me like that's an over-simplification, and I'm the one looking for the connections. It just seems too facile in the way that people say, “Oh, it's whimsical. It must be Lewis Carroll”. It feels like that's just a bit lazy.

RH: To get back to words like whimsical and eccentric, which I'm often described as. What’s whimsical about Lewis Carroll? It's like any deviation from meat-and-potatoes thinking and from filing-cabinet thinking is whimsical. It’s just having an imagination, for fuck’s sake. I mean, there are worse things to be called than eccentric, but it's like, sure, Michael Jackson was an eccentric, you know, does that help you define my music, or Michael Jackson's? It's terribly lazy.

In terms of Lewis Carroll influencing me, he was definitely part of the mental compost that certain minds grow out of. You know, John Lennon was a big fan as a boy, because, also in those days, there was no TV. If John was alive now he'd probably just be on social media the whole time. You know, clearly, a man with a lively mind but a short attention span, he'd have just been busy playing with all these things.

Because back 60-70 years ago all they had were comics, whichever ones they might have been. I don’t even know if they had The Eagle and Dan Dare and Lion and Tiger.

NC: Or The Beano?

RH: I think they were there before the Beano even. So really something like Alice in Wonderland was where you would go if you wanted your imagination to go for a walk.

And also it's very vivid. I read The Looking-Glass again a few years ago, and there's a lot of wisdom in it. There are puns and things like that as well. But what's most striking is how authoritarian everybody is. Everybody is always talking down to the child and getting angry with them. They're all kind of ‘bapping’ each other.

Everybody's what they used to call ‘uptight’, and they're sort of all struggling and fighting each other. Alice is the gentlest person in the book. There’s a lot of that whole “hoity-toity child”, you know, “mind your manners”. It must have been Victorian culture as Charles Dodgson saw it. And it's not very enticing.

NC: Wasn’t that also how it felt to The Beatles, and your generation? When the Beatles are playing on the roof, and you get those people walking around with bowler hats on, saying, “Oh dear! You know…I do understand that they need to play their music. But couldn't they do it more quickly, not on my lunch break”. Come on!

When they came into Abbey Road and you had all the sound engineers in white coats and all those rules. I feel like there was the same dynamic. Actually, it's very clear what that tension is. And even in the songs, like ‘She's Leaving Home’, you get that dynamic, don't you, between one generation and the next. So I feel like in both cases, there’s an interplay between, stuffy older generation and then this more childlike, youthful perspective. Does that ring true?

RH: Well, it's certainly how it seemed to us. We felt we were on the cusp of a glorious new dawn, which just turned us into a bunch of self-indulgent drug addicts and weak parents, bequeathing a load of broken families to the world and going, “er, I don't know, man”. I think in some ways we were really kind of clueless and spineless. I can see why the previous generation of uptight military squares were so upset by us, because we were so feckless and we also had all the things they didn't have. We were able to have sex outside marriage. We were able to indulge ourselves in lots of ways that they couldn't.

NC: I am curious about some of your songs, too, Robyn. I mean, I see there's the word ‘Wonderland’ in ‘1974’: “you're in funky denim Wonderland […] you and David Crosby and a bloke with no hand”. Amazing, amazing line. And “they’ve got hair in places most people haven't got brains”. My observation is probably that ‘Wonderland’ has just become a noun, right?

RH: It’s become a noun. I wasn't thinking of the looking-glass or the rabbit hole. I was thinking of more just that sort of hairy wasteland that, as the energy from 1967 dissipated, you were just left with a load of people who had long hair and smoked pot. But they were, you know, making ‘On The Buses’ or ‘Rising Damp’, or whatever.

NC: ‘Autumn Sunglasses’ is different, though? Tell me about that.

RH: Oooh ‘Autumn Sunglasses’ …. I found myself living back on the Isle of Wight, where I often go between relationships, and this time I was renting the upstairs of a flat that Darwin and his wife Emma had lived in around 1859-1860 and next-door there's an arts centre. 100 years beforehand, Freshwater had been a kind of artists’ hipster colony. Alfred Tennyson was there. Julia Margaret Cameron, the photographer, was there. Darwin lived there for a bit, and another frequent visitor was your man Dodgson, Lewis Carroll, who was working on Through the Looking-Glass when he came down there.

I found my father's old copy of it and read it. And there was a lot of Looking-Glass-isms around. I think there was a Through The Looking-Glass event happening in the Arts Centre in Dimbola. Dimbola had been Julia Margaret Cameron's photography studio.

But it's also partly about the fact that I started going down to Australia, to Sydney when Emma and I had got together, but she was then back in Sydney.

“Get it right, also baby get it wrong

I'm still here, I've just changed where I belong

Through the walls, through the looking glass

Now you're gone

Your reflection remains”-Robyn Hitchcock, ‘Autumn Sunglasses’ (2017)

She had a DJ job for a while, and so I was commuting, as it were, between the Isle of Wight and Sydney, Australia. Going through the looking-glass, to me, meant going to the other side of the world. But when you get down there, what is so strange is how British it is. You know, the cars drive on the left. they've got the same confectionary, they've got Crunchie Bars, Aero, and Shreddies. They've got Vegemite instead of Marmite. And they've also got the same cultural stuff Emma grew up with, Carry On films and all that stuff. For me to meet someone, especially of her generation, that spoke Sid James and Barbara Windsor and Kenneth Williams, was quite amazing.

And so I just felt like I was somewhere really alien that was extremely familiar, which is really what happens when you go through the looking-glass. It's a lot of familiar ingredients, but they're not quite right. What's really strange is when things are a bit like you know them, but they're not doing what they usually do, which kind of brings you back to psychedelia. It's not like everything is suddenly covered in purple stalks, and howling around, with demons and angels fighting; it's actually “yes, I recognize all of this, but it's in a slightly different order”.

I think I really enjoyed the disorientation, or I savoured the disorientation. And that's really what that song is about, me just stepping into the next-door house on the Isle of Wight, but actually, I'm in Sydney, Australia.

NC: Like a portal, going through the walls…?

RH: I’m a huge believer in portals. And for me you know, the mirror is one portal, the rabbit hole is another. LSD was also seen as a portal. But again, nobody could really say you were any better for going through it. And a lot of times you would actually come out worse, the legacy of a bad trip, or just the disorientation of it. I never took very much LSD. People associate me with acid, because my musical heroes took a lot of it, but they also associate Lewis Carroll with acid. Partly because of that Jefferson Airplane song.

NC: ‘White Rabbit’!

RH: …completely. That song, more than anything, linked Alice with acid. And so often, when people try to find a quick way of defining me, they'll say things like “Alice in Wonderland logic”, or “mushroom logic”, or “it’s trippy, man”. But actually, it's not the drug. I never got as high from drugs as I did from reading about them.

NC: Why Autumn Sunglasses, though? Is that also about Autumn as in getting older?

RH: Well, since you ask, probably both. The title comes to me before I figure out what it means. Rather than “I want to get these ideas into a song”, I just had the title ‘Autumn Sunglasses’. The other thing, of course, is that it was Spring in Britain, but it was Autumn in Sydney. So I was alternating. When I left Britain in April, it was Spring, but I got there for Autumn, and then I came back here, and it was high Summer, and then I went back there and it was Winter. The Winters aren't as cold, so it was like your season was being mirrored. I had a pair of shades, and I was walking around in them. And also I was 60, so I always like getting into that zone of life. No one ever wants to be in their Winter of life. They're just in a protracted Autumn.

And there’s that rich, low, golden sunset light. I’ve got it in my song ‘I Often Dream Of Trains’ as well. It's one of my recurring dreams - very rich, golden sunlight, when it’s about to be Winter. Particularly in Enmore Park, which is where we lived in Sydney.

What's probably good about that song is it really captures how I felt. Certainly it captures it for me, but I don't know if that works for anybody else. When I sing it, I can absolutely feel that time. Songs for me are a way of bottling my experience and then constantly reliving them, because I'm very much not a guy who lives in the moment. I'm full of, “what should I do? What am I about to do? What can I make up?” Give me a guitar. Give me a pen. I can't just be. And in a funny way, I think my best songs actually force me to re-inhabit the life I was too impatient to be in. So I'll be back in this boathouse in the Isle of Wight in 1989 every time I sing ‘Glass Hotel’ and the songs of mine I like best are the ones that just bottle time. Hopefully when other people hear them they catch something of that flavour. Because in the end, what we're trying to do is just store our experiences and pass them on.

NC: So the songs are portals as well, right?

RH: They are portals. They should be. I mean, I'd like to think they are.

NC: We've done an hour, so I should let you go, Robyn, but is there anything I didn't ask you, or anything you want to say on this topic of Lewis Carroll? To sum up.

RH: Thanks for talking to me, and interviewing me on this topic. It's one that doesn't come my way a lot, and I enjoyed the blog. I - like you - am a fan of both Lewis Carroll and the Beatles. And I think they’re both gifts for life.

For more info on Robyn Hitchcock, the book, and his Patreon, check out his website.

Thanks for this. It’s nice to hear Robyn talking about something other than the usual questions. Bravo!

Great interview!

Autumn Sunglasses is one of my favorite songs ever.