02 Apples to Apples

Lewis Carroll 'herald of surrealism', Magritte & a tale of (two) Apple logo(s).

For my second post, I’m excited to take an idea for a walk. And that idea is surrealism. It’s a tale of bowler-hatted Belgian artist René Magritte, and how Paul’s acquisitions, together with Yoko Ono’s Apple, directly inspired the Apple Corps logo, launched in 1968, and how that in turn influenced Steve Jobs’ choice of a fruit for the Apple Computer brand. And, of course, how all these lead back to Alice.

Now if, like me, you’ve left it too late to catch Surréalisme, the major retrospective at the Pompidou Centre, don’t worry: it’s moving to Madrid and then Hamburg. Of course it is so appropriate that it’s currently in Paris, and that it has an Alice section, because it’s the championing of Carroll by French surrealism, first Louis Aragon (who translated a lot of Carroll) and subsequently Breton, that made the Alice books popular in France, and I think, accounts for the particularly surreal flavour of so many of the French illustrators of Alice (from Lacombe to Lostfish).1

Today though it’s René Magritte I want to talk about. Let’s start with the most obvious connection: yes, Magritte was a huge fan of Carroll, and yes, he painted Wonderland!

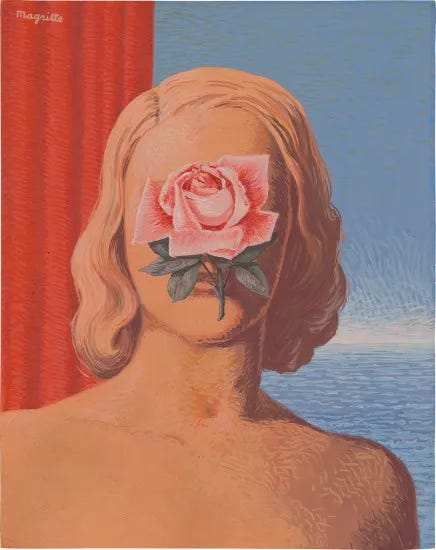

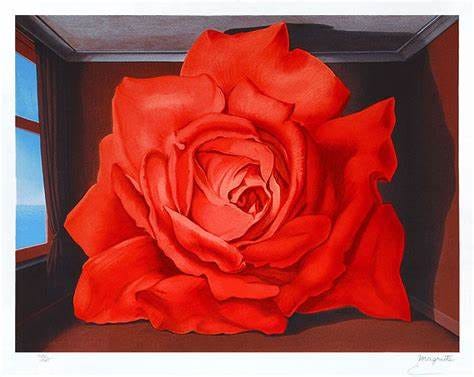

Here Magritte sees ''the tree [as…] alive in a world of marvels”.2 Assigning human qualities to things is part of the way both Carroll and Magritte make familiar environments less familiar, and destabilise our sense of reality. And that can be anything from grinning cats to talking roses, trees with faces, or simply everyday objects attaining human scale. Yes, this can sound philosophical, and it often is, but it’s also downright funny.

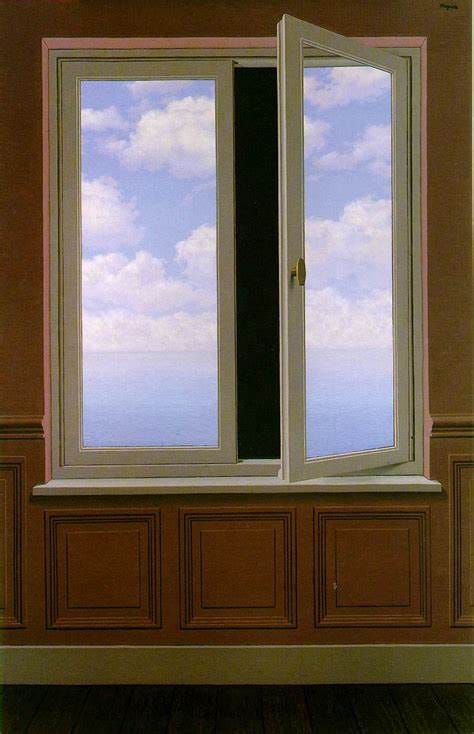

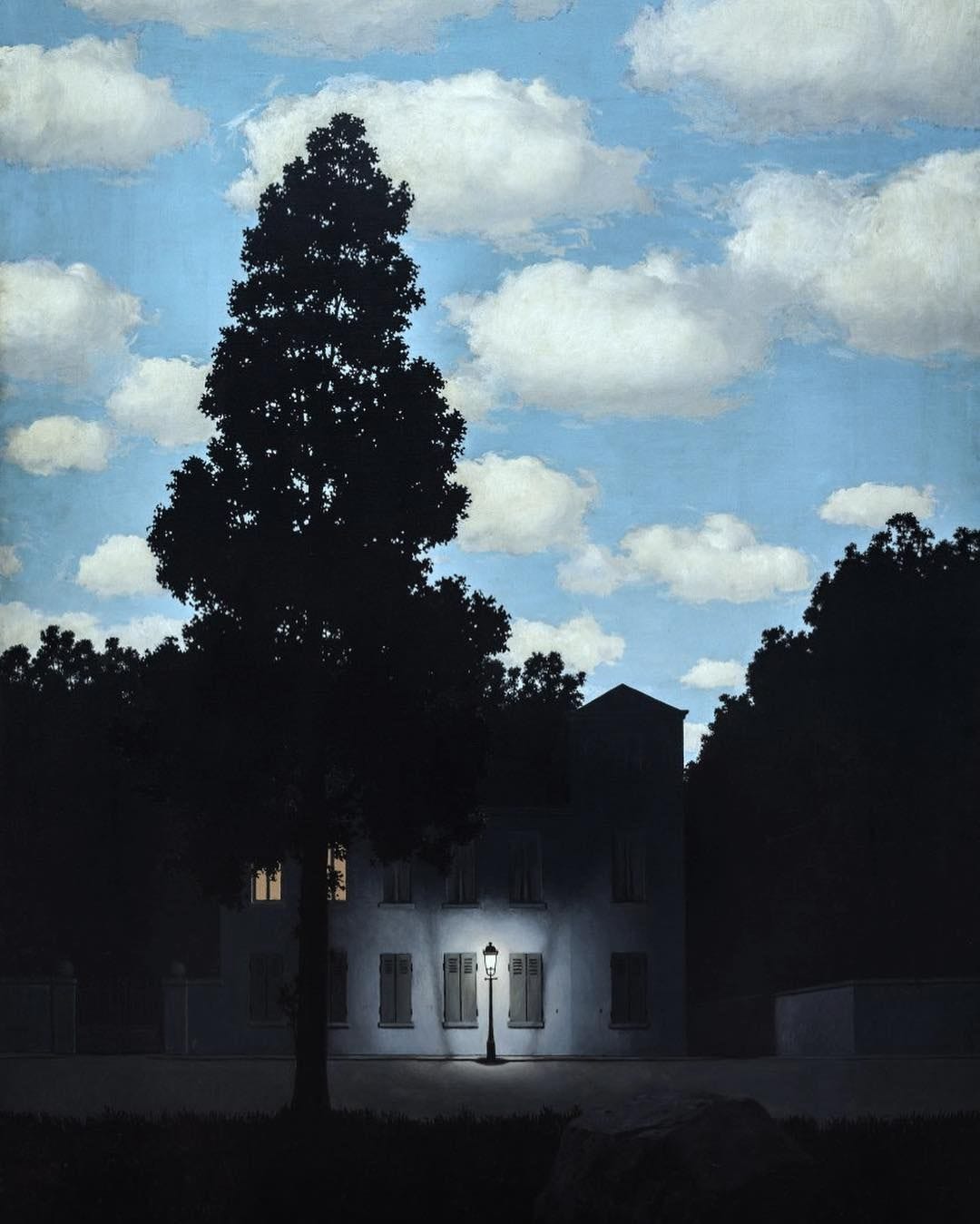

Another related tension is the fuzzy boundary between waking and dreaming, or night and day, that’s so inherent to nonsense and to dream-logic. Carroll’s opening to “The Walrus and the Carpenter” sets this up beautifully:

The sun was shining on the sea,

Shining with all his might:

He did his very best to make

The billows smooth and bright—

And this was odd, because it was

The middle of the night.-Lewis Carroll, Through The Looking-Glass (1871)

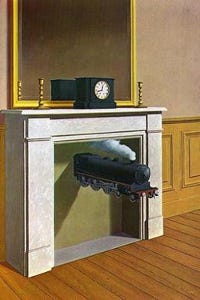

It’s a theme Magritte would play with in no fewer than 27 paintings (both oils and gouaches) between 1940 and 1960, but most famously in L'Empire des lumières (The Empire of Light or The Dominion of Light, depending on the translation):

The “real world” paradox of night and day co-existing is not a problem for the imagination. Magritte relishes the looseness and subjectivity in the relationship between signifier and signified, and loves playing with it.

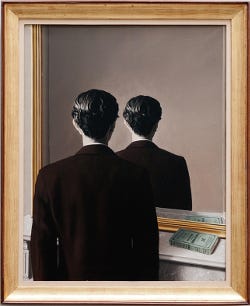

Of course there’s no better symbol for this than the mirror, or looking-glass, which crops up again and again, as a way of exploring the in-between, the liminal space, the ambiguous boundaries between worlds.

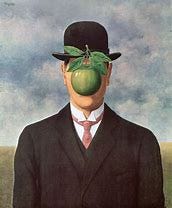

And then there are the apples. Light green, dark green, russet, blue, yellow & red, Magritte seems to have a thing about apples. They pop up again and again. Sometimes alone, sometimes as relationship symbols, and sometimes as more obvious references to Biblical apples.

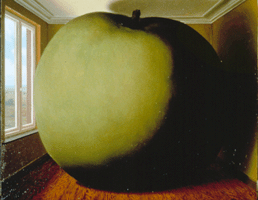

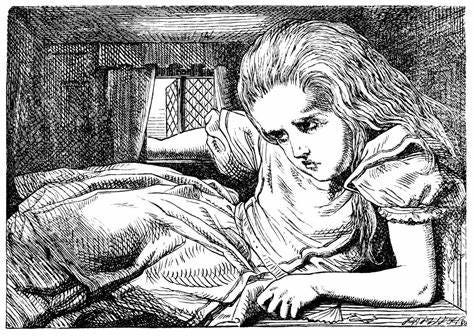

My favourite, by far, though, is La Chambre d'Écoute (‘The Listening Room’, 1952), because to my eyes, it so clearly references Tenniel’s drawing of Alice when she’s grown in size and is bursting out of the White Rabbit’s house. How ludicrous and out of place the apple looks - how did it even get into the room, being so large?!

We know it’s not by chance. The French surrealists, Magritte included, saw Carroll as a kind of prophet or ‘herald’, a path-finder for their work, and so did the Beatles:

“I like surrealist art, I also like surrealist words […] a great example of this is Lewis Carroll writing Alice in Wonderland – it’s a crazy thing, you’ve got a cat sitting in a tree that grins and talks, and you’ve got Alice falling down a hole and meeting the red queen, and so on. That whole tradition was something that I loved, and when I met John, I learned that he loved it too. So, it was something that became a bond between us.”

-Paul McCartney, interview on PaulMcCartney.com about ‘Uncle Albert / Admiral Halsey’ (2024)

Little surprise, then, that John & Paul also discovered a shared love of Magritte, which once he had the means, Paul turned into a collection too:

“I’ve always loved Mr Magritte’s work and have admired him since the 1960s when I first became aware of his work. I love his paintings so much that I once took a trip to Paris to visit Magritte’s art dealer Alexander Iolas and had a very pleasant meal in his apartment above the gallery. We then went downstairs to see the paintings and I was able to select three pictures.”

Paul McCartney – FromPaul McCartney | News | New Feature: Paintings On The Wall – René Magritte (1898 – 1967), March 2015

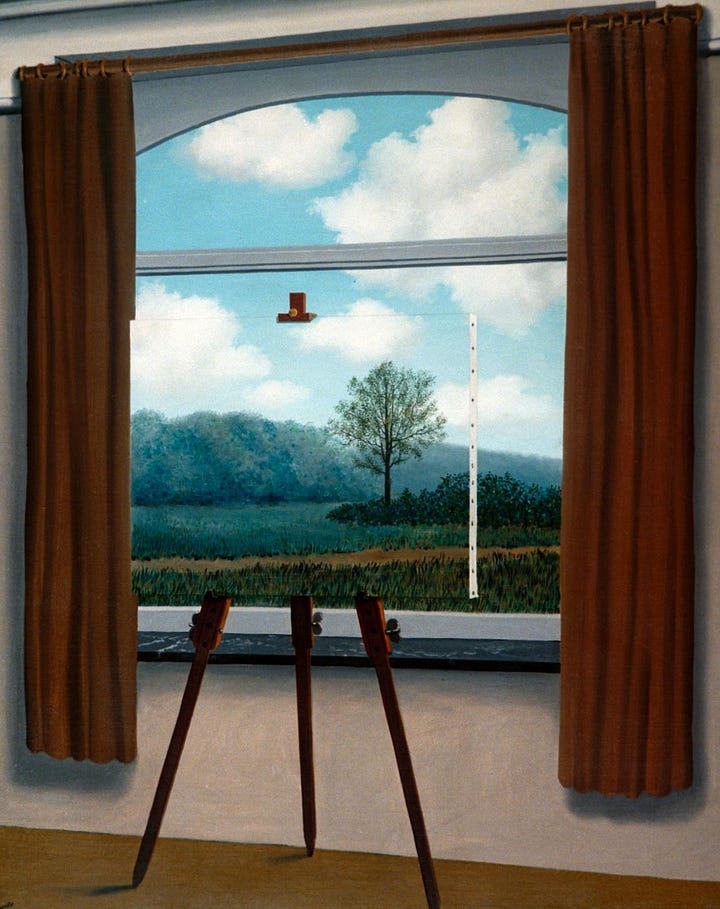

McCartney does seem to misremember the date on which he acquired Le Jeu de Mourre (1966), but it’s likely it was one of the three he acquired on this occasion. Certainly we know he already owned it in 1967 from photos taken in his Cavendish Ave home:

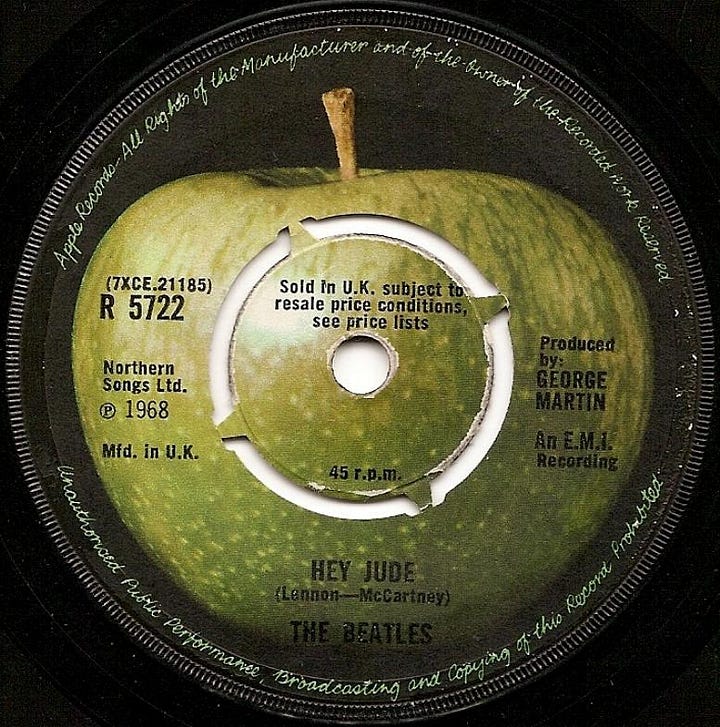

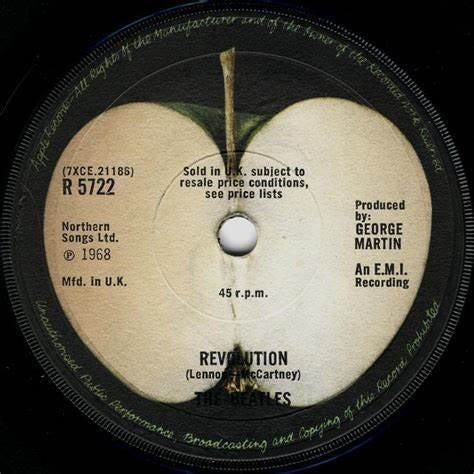

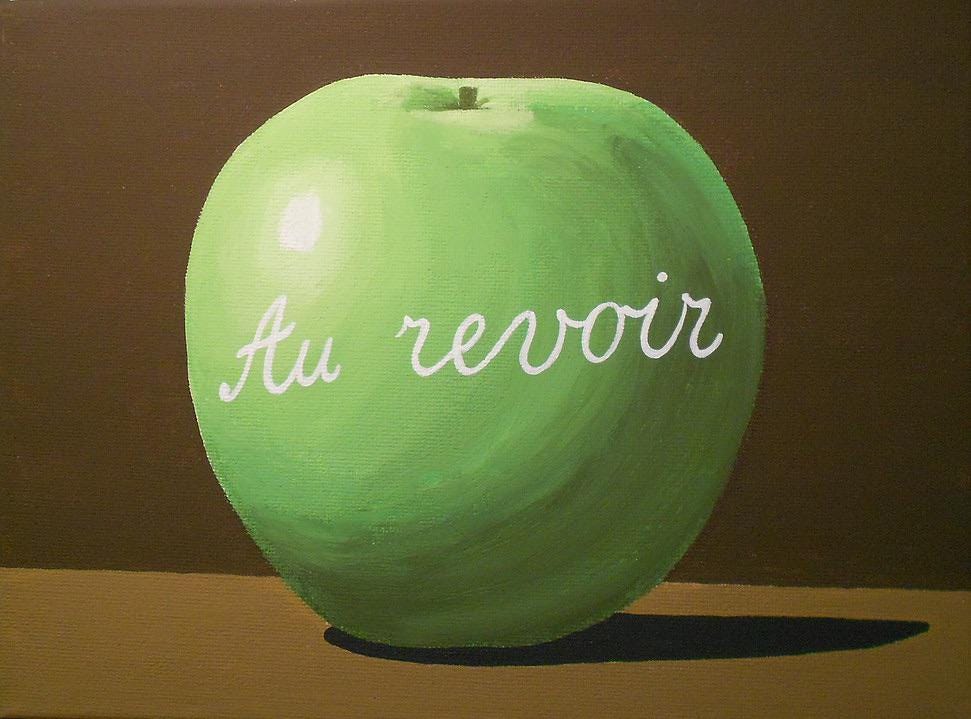

And so, drum roll… here it is, close up… the painting which McCartney said looked like a “calling card” and which inspired the logo for Apple Corps (a Carrollian play on words - corps = core). “This big green apple, which I still have now” he explains, “became the inspiration for the logo. And then we decided to cut it in half for the B-side!”.3

The Beatles, with a little help from Gene Mahon, interpreted the apple and turned it into an iconic record label. Its first outing? The ‘Hey Jude’ / ‘Revolution’ single.

I wonder whether there isn’t a missing step in the story, though: Yoko Ono. After all her Apple was on display at her exhibition at the Indica Gallery in 1966, when John and Yoko met. Does this not look familiar?

That these two artworks (Apple and Le Jeu de Mourre) turn up in the Beatles’ lives so close to each other is tantalising. It’s a coincidence I can’t ignore. What’s more Yoko has this to say:

In the beginning, art was what we talked about. [John] told me he thought he was like Magritte. Why? Because, you know, you have the image of Magritte with the bowler hat and the suit, looking very square, but really his work was very surreal and far out. John was living in suburbia, and he was very embarrassed about that, because he felt as if he was not very hip. When he invited me to his house the first time, the first thing he said when I got there was, “I think of myself as Magritte.”

— Yoko Ono, interviewed for The New York Times (7 October 2004).

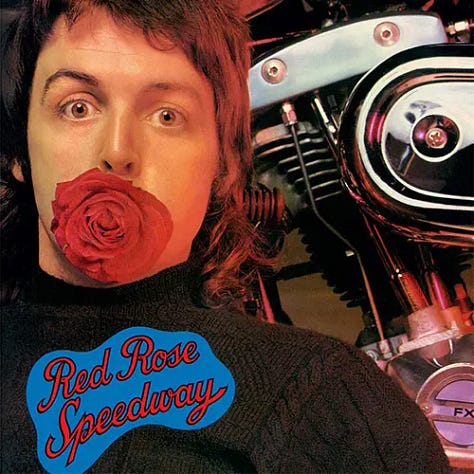

And it doesn’t stop there. McCartney’s Magrittery keeps showing up throughout the 1970s. I’ll save a run-down on Paul’s lyric surrealism in songs like ‘Uncle Albert / Admiral Halsey’, but while we’re talking visuals, I can’t be alone in seeing the Red Rose Speedway artwork as - among other things - a riff on the Belgian’s roses.

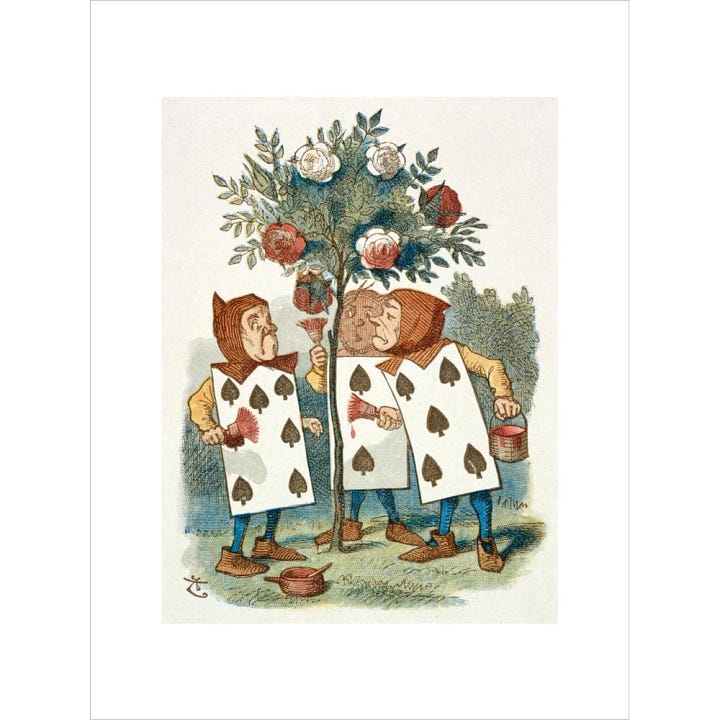

And maybe that ties back into Through The Looking-Glass, in the chapter with talking flowers? Or Alice in Wonderland, where Alice finds the playing cards furiously painting the roses red:

“Would you tell me please,” said Alice, a little timidly, “why you are painting those roses?” Five and Seven said nothing, but looked at Two. Two began in a low voice, “Why, the fact is, you see, miss, this here ought to have been a red rose-tree, and we put a white one in by mistake; and if the Queen was to find it out, we should all have our heads cut off, you know.

- Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, ch.8.

It’s two things at once: a manifestation of the Queen of Hearts and her absurd and irrascible demands, and simultaneously another reality paradox - begging the question of what’s real and what’s artifice.

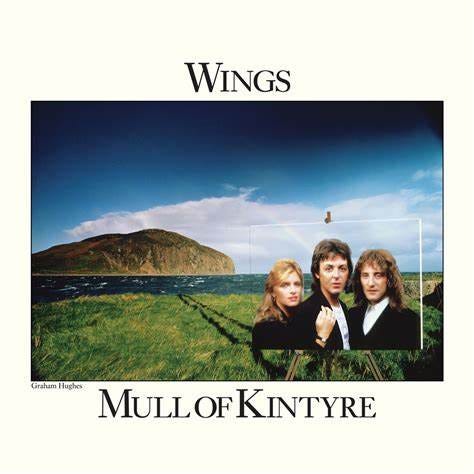

Fast forward 4 years, and look, what’s that on the cover of Wings’ ‘Mull of Kintyre’ single? It does take a while if you’re not looking for it, but once seen…!

Surrealism (in words and images) is a real hallmark of the Beatles’ creative approach, both during and in their solo careers. The only thing about these connections that surprises me is that they’re not better known. After all Lennon went to art college in Liverpool4 and grew up passionate about drawing (including copying Alice characters). And he always pursued a very playful, punning, approach. Just how Cheshire Cat-like is this cartoon? And how typical to see the “owl hooting” visual pun!5

Paul still paints (and you can see his work on the covers of Egypt Station (2018) and his Fireman albums, for example). And of course, Yoko Ono’s conceptual approach to art - celebrated so powerfully in last year’s Music of the Mind exhibition, where I got to see Apple, as well as hammer nails into a block - influenced songs like ‘Julia’ or ‘Revolution 9’ (both on the White Album), and the reversed arpeggios on ‘Because’ (Moonlight Sonata backwards), just for starters.6

And onto Steve Jobs, who studied calligraphy and set out to make Apple as beautiful as it was functional. The apple itself, for him, was a symbol of knowledge, but also the start of the alphabet, hence easy to find and remember. And while Jobs inspiration for the Macintosh apple, specifically, was sparked by working on an orchard as a young man, it’s also a clear nod to the fab four. In fact, Jobs’ whole approach was influenced by their creative partnership: “my model for business is the Beatles”, he once said.7

What a beautiful creative conversation (from books to business) across time: Carroll>Aragon>Breton>Magritte>Fraser>McCartney&Ono>Apple Corps>Apple Computer

Next time we’ll be tackling a big one: the double whammy of ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ / ‘Penny Lane’ (surely pop’s best ever double A-side). And the nexus of memory, fantasy, childhood. A place where nothing is real…

Until then.

Thanks for reading!

Sources

The Paul McCartney Project, especially this article on Magritte

Lewis Carroll Resources, maintained by Mark and Catherine Richards

’Something borrowed, something new’, The Tate online.

An article on surrealism manifestos

The Art of John Lennon website

Many Years from Now, Barry Miles (1997)

Surréalice, catalogue of the Museum of Strasbourg 2022 exhibition

This is a massive and complex topic. But for starters, check out Justine Houyaux “Through the Surrealist Kaleidoscope” in Kohlt & Houyaux (eds.) Alice Through the Looking-Glass: A Companion: 13 (Genre Fiction and Film Companions), Peter Lang, (2024) & Mark Richards’ fabulous online resources include a page devoted to Carroll and Surrealism. For the French readers, this is excellent and packed with imagery: Surréalice, exhibition catalogue (Museum of Strasbourg, 2022).

Sotheby's summary of the work says the following: “Even though it is not a depiction of any particular incident in the original story, Magritte's Alice in Wonderland is inspired by the fantastical world which Carroll described so vividly in his writing. ''The tree is imagined to be alive in a world of marvels,'' the artist wrote of this work. ''To this end, the landscape and the tree have been given human features'' (ibid.) [….and later] “The imagery that he has chosen for this picture, although nominally based on Lewis Carroll's tale, refers to the famous caricatures of Louis-Philippe by the 19th century French draftsman Honoré Daumier, in which the French king is depicted as a gluttonous monster with a pear-shaped head”.

1993 interview.

Liverpool Art Institute 1957-60.

Check out The Art of John Lennon if you fancy snapping one up.

McCartney later said of Yoko “She wanted more, do it more, do it double, be more daring, take all your clothes off. She always pushed him, which he liked. Nobody had ever pushed him. Nobody had ever pushed him like that. We all thought we were far-out boys, but we kind of understood that we’d never get quite that far out.” quoted in ‘The mammoth impact of Yoko Ono on The Beatles’, Drew Wardle, Far Out magazine.

“Everything we see hides another thing, we always want to see what is hidden by what we see. There is an interest in that which is hidden and which the visible does not show us." Rene Magritte