03 Nothing is Real...

Childhood, memory and pop's greatest double A-side: 'Strawberry Fields Forever' / 'Penny Lane'.

“I wanted to write Alice in Wonderland and be Elvis Presley”

John Lennon.

Today, I’d like to take you down, to the heady days of 1966/67. To the Beatles’ greatest single, the blossoming of psychedelia, and two songs that on the face of it share little in terms of personality.

Where Penny Lane is bright and breezy (“clean” sounding to quote McCartney), Strawberry Fields is murky and “swimmy”-sounding. Where McCartney’s ode to Liverpool is extroverted and exuberant, Lennon’s is more introspective and conflicted. Yet both play with memory, place, childhood and the notion of reality in ways that make them perfect foils for each other.

«« Rewind.

In July 1966 England beat Germany to lift the (football) World Cup for the first (and last, so far…) time.

In August, The Beatles play their last ever (public) concert at Candlestick Park ending a strange period where, after recording revolutionary tracks for Revolver like ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’, they have to go back on tour and play Long Tall Sally and Baby’s in Black,1 while the “bigger than Jesus” controversy continues to dog their every move.

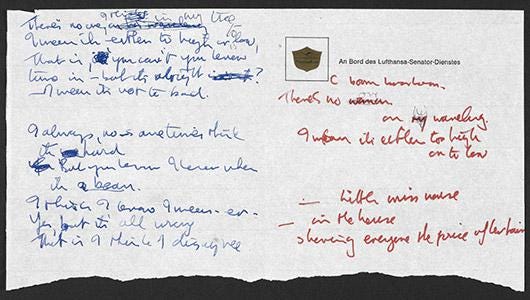

In September John travels to Almeria, Spain, to start filming How I Won The War, a Dick Lester black comedy. It’s during this time, released from the shackles of touring, that he writes the Beatles song he remained most proud of, ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’.

»» Fast forward.

In 2018 we took a trip to Liverpool to see Paul McCartney play the Echo Arena, and to take the Magical Mystery Tour round some of the mythical Beatles sites: the childhood homes of John, Paul, George & Ringo, the Cavern Club, and of course, the two places immortalised in song.

Ostensibly these two songs are songs about places. They’re rooted in geography. And time. The specificity of these places is not to be denied; just for example, social geographers are right to be interested in things like the growing bus system in Liverpool and its contribution to mobility (physical, cultural and societal). It’s one of the reasons the Beatles were able to travel across Liverpool (and to learn the B7 chord according to a famous anecdote).

And yet… much as I enjoyed visiting the place (and getting the photo) it’s ultimately nothing to do with geography, and everything to do with feelings.

> Play.

“We always had fun at Strawberry Fields. So that's where I got the name. But I used it as an image.”

-John Lennon, Playboy interview (1980)

More than a real place, Strawberry Fields is a symbolic place, it’s “anywhere you want to go". It’s what it represents that counts, and that’s not ‘real’ in the conventional sense, it’s a cipher for personal, subjective, reality. And in John’s case, psychological reality, self-doubt, the sense that he’s special, uniquely gifted, able to see things others can’t, or perhaps just a madman.

“I was always hip. I was hip in kindergarten. I was different from the others. I was different all my life. The second verse goes, “No one I think is in my tree.” Well, I was too shy and self-doubting. Nobody seems to be as hip as me is what I was saying. Therefore, I must be crazy or a genius — “I mean it must be high or low,” the next line. There was something wrong with me, I thought, because I seemed to see things other people didn’t see. I thought I was crazy or an egomaniac for claiming to see things other people didn’t see.

—John Lennon, Interview, Playboy, 1980

For the Lewis Carroll fans in the house, this tension between sanity and madness, clarity and confusion, should sound like a familiar dynamic. But there are other parallels too. The song itself is structured as a voyage, an internal journey, a conversation, with John as our quasi-White Rabbit guide:

Let me take you down

'Cause I'm going to Strawberry Fields

This linguistic move, a gentle command, the “let me take you…” is one of the ways the Beatles repeatedly draw on Lewis Carroll.

“To me and John, though I can’t really speak for him, words like ‘imagine’ and ‘picture’ were from Lewis Carroll. This idea of asking your listener to imagine, ‘Come with me if you will…’, ‘Enter please into my…’, […] It drew you in. It was a good little trick, that. Both of us loved Lewis Carroll and the Alice books and were fascinated by his surreal world”.

-Paul McCartney, The Lyrics, (2021)

It shows up first in ‘I’ll Get You’ (1963) (“Imagine I’m in love with you…”), it crops up in 1971 on John’s ‘Imagine’ (“imagine all the people…”), but it would only be a matter of months before ‘Lucy In the Sky With Diamonds’, the most explicitly Carrollian song of all. “We did the whole thing like an Alice in Wonderland idea”, Paul says, and part of that is the idea of a call to the imagination, hence the opening phrase “picture yourself on a boat on a river”.

I asked Julia Baird (John’s half-sister, and author of Imagine This: Growing Up With My Brother, John Lennon) what she made of John’s obsession with Lewis Carroll. She was kind enough to reply.

"Everyone read Alice and Through the LG… [it was] part of our childhoods post war… we all loved the fantasy aspect and knew the stories well […] it was everyone’s book both in primary school and at home […] Also Edward Lear’s limericks… we read at home and learned by heart in school ... [but it was] more a cultural sphere than a John sphere. Post-war fantasy”

-Julia Baird, email correspondance with the author, 2024.

While I think I was hoping for some unknown nugget of insight, I’m actually really glad that Julia chose to point out the broader impact, the ‘cultural sphere’ as she puts it, of Carroll, Lear and the like, in the fuelling of post-war optimism, and the escape from the drab and dreary, black-and-white, Britain of the 40s.

While not yet the technicolour Swinging London of the 60s, the 50s marked the emergence of a new generation, the birth of the teenager, and of youth culture more generally. In 1950, a new children’s classic, C.S.Lewis’ The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe, hit the bookshelves.

The tardis-like idea of escape from the normal realm, entering a portal, through a wardrobe, into a hidden Narnia, continues a red thread in children’s writing, from Wonderland to The Secret Garden, and onto Lewis.

It’s hard to underestimate the importance of child heroines (and heroes) in these stories as emblematic of a cultural shift, especially the sense that children, and their personal reality, are often misunderstood. But simultaneously that their imagination and curiosity hold the keys to escape.

Alice finds the magical garden:

Just as she said this, she noticed that one of the trees had a door leading right into it. “That’s very curious!” she thought. “But everything’s curious today. I think I may as well go in at once.” And in she went.

Once more she found herself in the long hall, and close to the little glass table. “Now, I’ll manage better this time,” she said to herself, and began by taking the little golden key, and unlocking the door that led into the garden. Then she went to work nibbling at the mushroom (she had kept a piece of it in her pocket) till she was about a foot high: then she walked down the little passage: and then—she found herself at last in the beautiful garden, among the bright flower-beds and the cool fountains.

-Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865)

These ‘portal’ moments seem to dramatise the childhood yearning for escape & freedom, and the power of childlike imagination to offer up glimpses of an alternative reality.2

The idea of reality is a central problem of Alice’s world. The Victorians were fascinated by in-between worlds, death, dream and much more and this definitely flows through Carroll’s imagination. John found huge solace in writing about outsiderdom, and solace in tales of misfits, like Alice, but he was also reading Hindu teachings on set, and was drawn to the idea of ‘maya’ (or the cosmic illusion that the phenomenal world is real).

Nothing is real

And nothing to get hung about

Strawberry Fields forever

John vacillates between what’s real and what’s not, what’s right and what’s wrong. Uncertainty’s woven throughout, with its “I think”, “I know”, “I mean”, “yes”, “it’s all wrong”:

Always, no sometimes, think it's me

But you know I know when it's a dream

I think I know I mean a yes

But it's all wrong

That is I think I disagree

It does remind me of how, in Alice, the thing and the opposite of the thing, presence / absence, certainty & doubt coexist strangely, as in the Mad Hatter’s Tea Party:

“Have some wine,” the March Hare said in an encouraging tone. Alice looked all round the table, but there was nothing on it but tea. “I don’t see any wine,” she remarked. “There isn’t any,” said the March Hare.

Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland (1865).

So the song is riven with doubt, but it’s also strangely confident. The refrain signals positivity and hope, especially in the power of the imagination (which for me is the defining trait of Alice’s (creative) journey. And if the lyrics are a conversational journey, ‘taking us down…’ to a symbolic magic garden, the recording and subsequent video promo only add to the unreal/surreal atmosphere.

Sonically it’s an altered reality soup, with big chunks of synthetic and analog, classical and Indian instruments, forwards and backwards sounds, and ultimately all ‘vari-sped’. The arrangement features a mellotron — both in Paul’s iconic flute-like prologue, and the ‘swinging flutes’ setting reversed in the fade-out — a descending raga-like run played on a Svarmandal, strings, trumpets (at points sounding like a fanfare, others like a hunting horn), reversed cymbals, timpani and much much more. To say they threw the kitchen sink at this one, in the record-breaking 55 hours of time in Abbey Road, would definitely be an understatement.

It also opens with the chorus (a classic Beatles move) and the melodic / harmonic interplay is often mildly dissonant. Having recorded a slower, more sparse version, and then a faster version with cellos and brass, Lennon made an impossible request: the final version is a stitched-together hybrid. One take had to be sped up and another slowed down to make the pitches match, all creating a swimmy, strange, psychedelic vocal feeling.

Formally. the song also features a false fade-out ending, with a dopplar-like free-form coda, that feels as though it’s coming in and out, or that we are opening and closing a sonic door, all the while John is almost inaudibly repeating ‘cranberry sauce, cranberry sauce, cranberry sauce’ (and not ‘Paul is dead’!).3 To hear this clearly, check out the version 7 on Anthology 2.

And so to the promo, which is full of backwards film (Paul leaping up into the tree), superposition, coloured paint being poured onto a piano, and — in an echo of last week’s post — a constant switching between day and night. Take a peek!

This night/day paradox takes us neatly onto ‘Penny Lane’, the other side of the single. It’s a song that seems light where Strawberry Fields is dark, optimistic and extrovert where Lennon’s song is introspective and unsure of itself. It’s 1966 exuberance in a bottle.

“With its vision of ‘blue suburban skies’ and boundlessly confident vigour, ‘Penny Lane’ distills the spirit of that time more perfectly than any other creative product of the mid-Sixties”. […it’s] thrilled to be alive.”

Ian McDonald, Revolution in the Head (1994).

Again, we went to have a look for ourselves:

Yes, there it is, the famous barber’s shop, the shelter “in the middle of the roundabout”, it’s all there, it’s all real. McCartney still loves driving down Penny Lane whenever he’s back, because “the characters […] are very real to me” (The Lyrics, p583).

And yet… in its own way, ‘Penny Lane’ is just as much post-war fantasy. We can see the fingerprints of Dylan Thomas on McCartney’s in the way vignettes of everyday life, and a cast of characters, are stitched together. He also intentionally transforms banal description, or documentary realism, into more poetic forms. The barber’s window display, for example, is framed as art gallery:

In Penny Lane, there is a barber showing photographs

Of every head he's had the pleasure to know

Meanwhile the fireman has an hourglass (an unlikely word for a clock or timepiece). The narrative slithers from Summer with its ‘blue suburban skies’ to poppy season (November) with the nurse, while the fireman ‘rushes in, in the pouring rain’.

‘Very strange’ indeed!

And then there’s the bit that McCartney himself has cited as “very Sixties”, a subversive meta-commentary and the sense of detachment, that we’re viewers of a spectacle where the players are aware they are in a play. Who dreamed whom?

And though she feels as if she's in a play

She is anyway

McCartney has said he was looking for a clean, Beach Boys-type of sound, but it’s anything but natural. The basic piano sound turns out to be 3 different pianos, one recorded half-speed, another through a Vox amp. The backing track was also recorded with the tape running slow so that it would sound faster on playback.

Harmonically the song moves around the circle of fifths, using dominant chords to cleverly get us from place to place in a way that’s emotionally satisfying and also creates space for the chorus to soar. With a bass line that steps down and then climbs back up, I’m reminded me of the idea of katabasis / anabasis as the Greeks called it, the descent / ascent dynamic of all ‘underground’ tales from Orpheus in the Underworld to Alice in Wonderland (remembering that Carroll’s first draft was called Alice’s Adventures Underground).

In case we were still thinking that Penny Lane is a song ‘about’ a street in Liverpool, the video adds yet more layers of strangeness with John Lennon constantly strolling on a kind of endless loop, the Beatles as riders in red coats on horses who dismount for a twisted tea party, drinking champagne out of China cups, and then have their instruments handed to them sitting at a table in the middle of nowhere decked out in linen and elaborate candlesticks.

Here it is in all its oddness.

The double A-side was released in 1967. Ludicrously it was rushed out because having not heard much from the Beatles in a few months, people were speculating they’d split up. There’s no way someone like me can truly understand the before and after. You literally had to be there. Contemporary accounts show it felt revolutionary, subversive, exciting, like nothing people had heard before. And spare a thought for Brian Wilson, who was driving when he first heard ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’, had to pull over in his car, broke down in tears, and apparently said, “they got there first”.4

It’s not their biggest hit. But it’s their best song pairing. And hard to beat.

IMHO.

What do you think?

Candlestick Park setlist. August 29th 1966: 1. Rock and Roll Music 2. She's a Woman 3. If I Needed Someone 4. Day Tripper 5. Baby's in Black 6. I Feel Fine 7. Yesterday 8. I Wanna Be Your Man 9. Nowhere Man 10. Paperback Writer 11.Long Tall Sally.

Thanks to my friend Lucia Komljen for making the link between gateways and portals more clear for me.

Somehow in English culture, madness is often encoded verbally. In Carry On Up The Khyber (1968) it’s the sight of Brother Belcher slowly losing his mind — furiously squawking “Strawberry Mousse, Strawberry Mousse” — that encapsulates the madness of the scene with the dinner party continuing while the residence is bombed.

https://500songs.com/podcast/episode-145-tomorrow-never-knows-by-the-beatles/