This won’t be about Oasis, I promise. Yes, this is where they got their song title from; but we’re here to talk Alice, so enough said!

Now I’ve spent the last few weeks concentrating on Lennon & McCartney’s obsession with Lewis Carroll, for good reason. The pair have both repeatedly talked about Carroll as an influence. And in the list I’m building, there are just more songs of theirs to go on.

But part of my aim with the project is to shine a light in less expected places, to tread the path less travelled. And that, dear readers, means creating space for George and Ringo. To show how they too, cross paths with Alice.

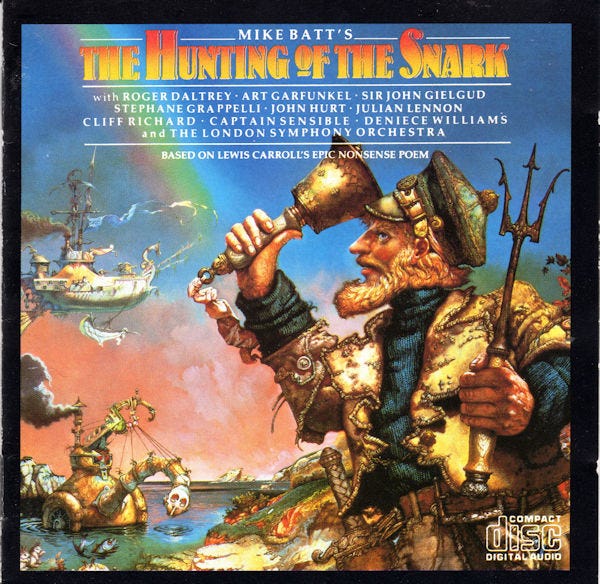

So, for example, while it’s probably not worth a whole post right now, did you know Ringo played the Mock Turtle in a 1985 TV adaptation? Or that George Harrison played guitar on Mike Batt’s album version of Hunting of the Snark (a recording that also includes Julian Lennon)?

And if we made a list of most misquoted Alice sayings, this would be close to the top:

“If you don’t know where you are going, any road will get you there”

The source? No, not Alice in Wonderland (though that’s almost certainly the inspiration).1 In fact, it’s George Harrison and his last single, ‘Any Road’ from 2003’s posthumous release Brainwashed.

(I’ll probably do another post on this topic in due course).

Anyroad… speaking of Wonderland, let’s get back to Wonderwall.

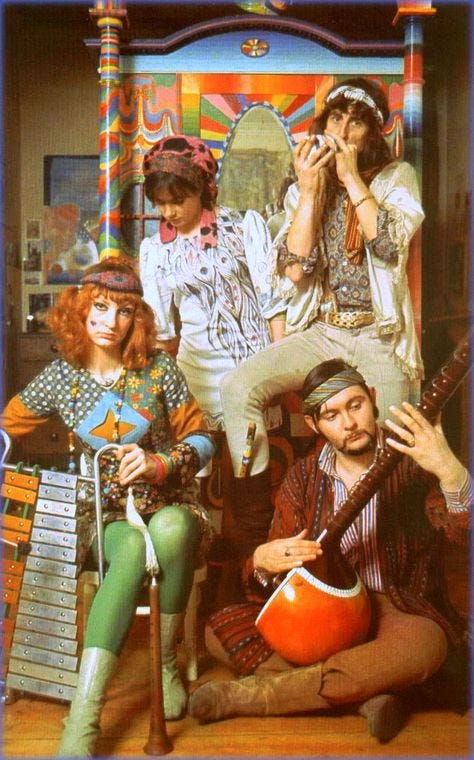

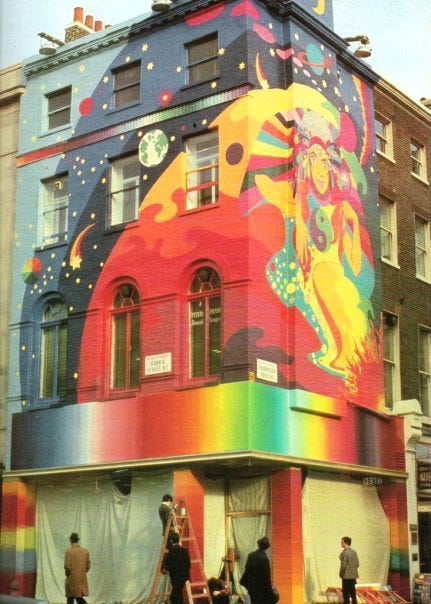

It all starts in 1966, when artists Marijke Koger and Simon Posthuma (who branded themselves ‘The Fool’, after the tarot card) are living as part of a hippie set in Ibiza. They come to public attention because of Karl Ferris’ photos of their clothes and art published in The Times. Before long they have become the most celebrated artists of the psychedelic era in London. And go-to designers for the Beatles.

If you didn’t know much about them before, you’ve definitely seen their work because it’s the outfits for ‘All You Need is Love’ and ‘I am the Walrus’, a few guitars and cars, and perhaps most famously, the 3-storey Apple Boutique on Baker Street:

Less well known, I’ve found, is the furniture they painted. Marijke’s online blog memoir is a treasure trove and in one episode she explains how they decided to turn a wardrobe into something more wondrous when they moved into their London apartment:

“An old armoire stood beneath the three arches dividing the living room, which made me think of “the Witch and the Wardrobe” and “Alice in Wonderland”. We decided to paint it in polychrome psychedelic rainbows and sinuous undulating forms, finished with my emblem of Sun, Moon and Stars and topped with a painted bust of Venus. We named it the “Wonderwall.” This would be the first piece of art anyone who entered the room saw and it would stop them in their tracks.”

-Marijke Koger, online memoir. 2

Here they are with the Wonderwall — and it certainly is a beauty!

The Beatles were smitten the minute they set eyes on it, and also on Marijke, who would soon have a fling with Paul. During this period she often read tarot cards for him, which was one of the inspirations for ‘The Fool on the Hill’. McCartney says the song is a portrait of the Maharishi, “perfectly still in the midst of the hurly-burly”3 though personally I’m also always reminded of Edward Lear’s Quangle-Wangle’s Hat.

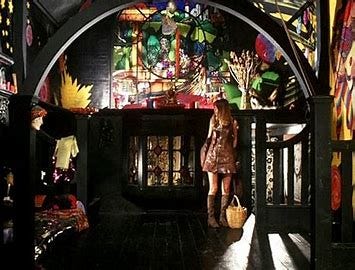

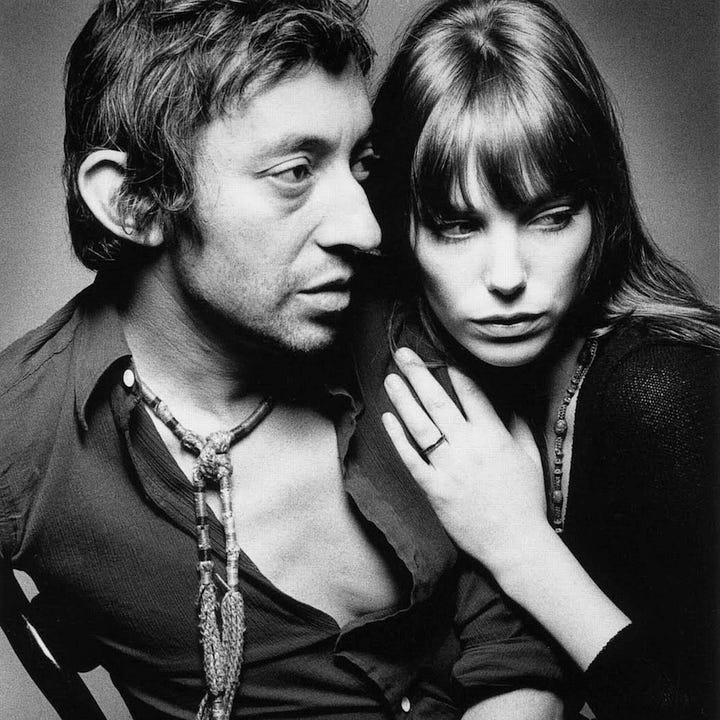

The Wonderwall would soon give its name to a movie, from 1968, directed by Joe Mossat, and which contains painted armoires aplenty. The ‘plot’ follows Professor Oscar Collins, an eccentric scientist who becomes obsessed with his neighbour (model ‘Penny Lane’, played by Jane Birkin), whom he watches through a peephole.

‘Penny Lane’? I mean, come on — could it be any more perfect!

The transition from world to world — peephole as portal — speaks to altered states of mind, but also sets 60s aesthetics against the still then quite conservative, and uptight, society it was challenging.

“When I came to England I was able to see those two societies quite clearly. British society was evolving and the old bowler hat world was dying […] in the film there are a couple of moments where Jack [the professor played by Jack MacGowran] goes black and white, it switches. That was meant to define that.

-Joe Massot, Wonderwall director.

Of course The Fool were hired to create the set and they also make a musical cameo. It’s worth watching a few minutes.

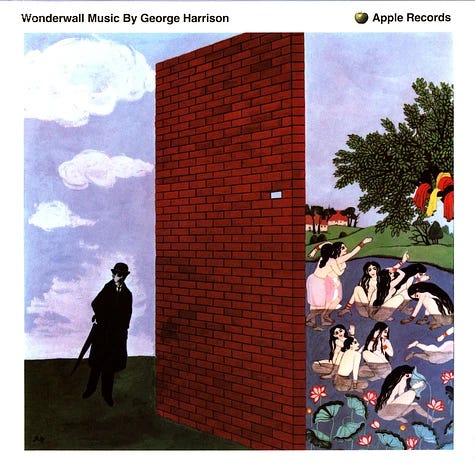

In yet another coming together of the 60s ‘scenius’ (to use Eno’s term), the soundtrack was recorded by George Harrison, and released as Wonderwall Music. It blends Western and Indian styles and thus foreshadows some of what would later be called world music. The recording sessions were split between Bombay and London (Abbey Road) and yielded other content that showed up as Beatles releases (‘The Inner Light’).

Apple commissioned Bob Gill to create the cover, painted in a Magritte style, which depicts a man in formal dress "separated by a huge red brick wall from a group of happy bathing Indian maidens".4 I picked up this very cool zoetrope edition, made for Record Store Day last year.

But in order to get to why Wonderwall is so significant, to our story, we need to take a slight detour back to 1966 and the most significant Alice adaptation of the 60s, Jonathan Miller’s TV film, a darker, more naturalistic, deeply psychological interpretation.

Miller’s fascinated by the tension in the way the Victorians saw childhood; it’s ’a short, unruly episode set aside with the express purpose of training the sober, responsible adult’ and yet ‘the innocent child was often closer to wisdom and sensitivity than they in their grown-up gravity could ever hope for. 3

Apparently the BBC flagged it as having ‘adult themes’ which caused a bit of a furore at the time.

"Once you take the animal heads off, you begin to see what it's all about. A small child, surrounded by hurrying, worried people, thinking 'Is that what being grown up is like?

Jonathan Miller

The strangeness of the child’s perspective in an adult world is conveyed photographically, through the use of odd camera angles and framing.

Miller also decided to emphasise the Empire associations of Victorian England, by asking Ravi Shankar to compose a soundtrack played by Indian musicians, and thus underscore the 19th Century Orientalism implicit in Victorian England.

It was, of course, George Harrison who was Shankar’s biggest proponent and made the introduction to Miller, additionally dropping into some of the recording sessions himself. And in return Shankar who introduced George to the Indian musicians he would hire to help make Wonderwall Music a year or more later.

Moving between these worlds and perspectives becomes the theme of the decade, its defining dialectic:

Reality / Illusion

Waking / Dreaming

B&W / Technicolour

Bowler Hats / Granny Takes a Trip

London / Bombay

For all the differences in age, in dress (and undress), and in outlook, I find some similarities in the gaze of Alice and Penny. An innocent / knowing dynamic. As if Alice grown-up and liberated, released from B&W, bowler-hatted, boredom, turns into Penny Lane.

When we get to our Lucy episode we’ll look at the dreamchild archetype. But for now let’s imagine that Penny Lane is part Alice. Part Dreamchild. Just as the ‘girl with kaleidoscope eyes’ is both Alice and Yoko. And Julia, with her ‘sea-shell eyes’ is Julia the mother, and Yoko, and no doubt a bit Alice too.

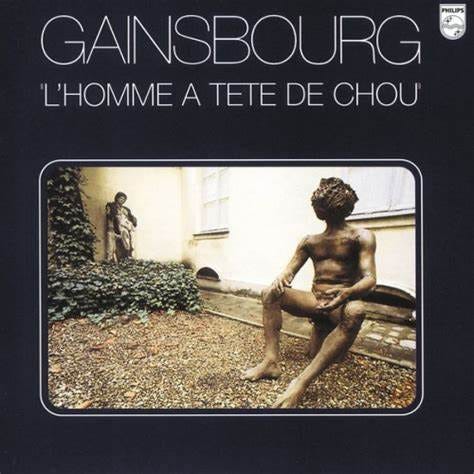

Shortly after filming Wonderwall, Jane Birkin became Serge Gainsbourg’s muse. And the dreamchild takes on a yet more erotic guise. Lewis / Levi’s, and Alice v malice, in ‘Variations sur Marylou’ (from L'Homme à tête de chou, Gainsbourg’s 1976 concept album about a man in his 40s falling in love with a shampoo-girl).

Dans son regard absent et son iris absinthe

Tandis que Marilou s'amuse à faire des volutes de sèches au menthol

Entre deux bulles de comic strip

Tout en jouant avec le zip de ses "Levi's"

Je lis le vice et je pense à Carol Lewis[…]

Arrivée au pubis, de son sexe corail écartant la corolle

Prise au bord du calice de Vertigo, Alice s'enfonce jusqu'à l'os

Au pays des malices de Lewis Carroll

And yes, it’s Oasis who brought the Wonderwall back to life, and the Alice thread without knowing it.

“Alice: Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?

The Cheshire Cat: That depends a good deal on where you want to get to.

Alice: I don't much care where.

The Cheshire Cat: Then it doesn't much matter which way you go.

Alice: ...So long as I get somewhere.

The Cheshire Cat: Oh, you're sure to do that, if only you walk long enough.”

―Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

Marijke’s blog memoir is super helpful and highly recommended. Unfortunately she declined to add to what’s published here, so we can assume it’s as definitive as she thinks it can be.

Paul McCartney, The Lyrics, p176.

Spizer.

Fascinating! Lots I did not know here … the parallels are growing more numerous …!