07 Studio Wonderland

Alice, parable of creativity, and the Beatles experiments in sound

Each week in Alice & The Eggmen, we explore the weave of connections between Lewis Carroll and the Beatles. Lots of it is not ‘new news’; John and Paul have both publicly claimed Carroll as a major influence (and we know John was borderline obsessive, re-reading the books yearly).

We’ll tackle the most obvious references in due course, when we cover ‘Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds’ and ‘I am the Walrus’. We’ll also see how Carroll’s use of language is a touchstone for many McCartney songs — both in the early days, and also well into his solo career. All still to come.

However — and it’s a big however…

In today’s episode I’m going to try to convince you that the ‘intertextual’ references (quotes, characters, words, language) are really only the beginning. My claim is that Carrollian techniques can be seen as creative moves that — directly or indirectly — influenced the Beatles musical innovations (harmonic, structural & sonic). And that Wonderland can be seen as a parable for the creative process.

If you’re still in doubt, tune in next week for an interview with a sound engineer working on the original tapes for the Beatles remix projects. We get into it fully!

[…]

To make the link we need to remember just how musical Wonderland is.

This week I’d like to start with Kiera Vaclavik and her insight that “the Alice books and their author” — rather like Victorian children — have “been almost exclusively seen rather than heard by critics” (emphasis my own).1

I’m so glad Kiera has done this analysis, because it’s an important counterbalance. It opens up a line of enquiry where Carroll can be seen as a musical — and not just storytelling, or linguistic — innovator. And while I’m mainly interested in the Beatles, let’s not forget how rich and deep that musical legacy is, from Donovan to Bolan to Slick to Batt to Albarn (wonder.land) and even Little Simz.

So while I think it’s not often how we first think of Carroll, once pointed out, it’s really obvious. The Alice books are very ‘noisy’ books:

Wonderland is essentially sound-based, with grass rustling, the mouse splashing, teacups rattling, plates crashing, the pig-baby sneezing, the Gryphon shrieking, a pencil squeaking and a suppressed guinea pig choking.

Kiera Vaclavik, ‘Listening to the Alice Books’ (2021)

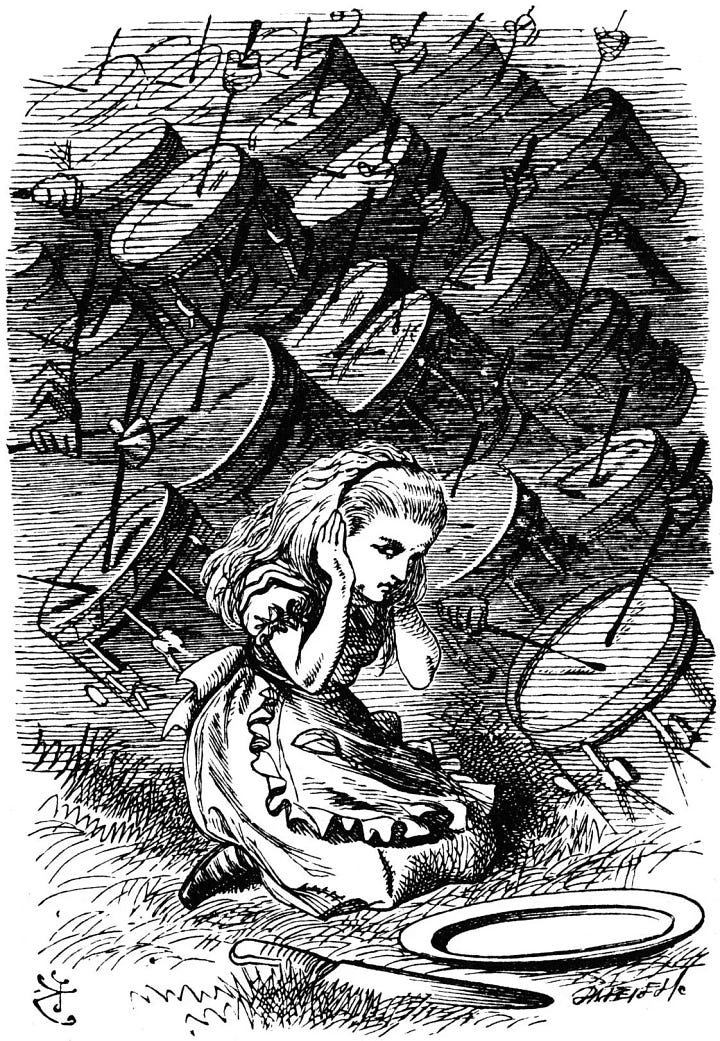

It’s there in the first illustrations too - the mad Hatter, open-mouthed, singing, and Alice shielding her ears from the dreadful din of drums. Just for starters…

More importantly — and I think it’s why Vaclavik identifies Carroll as a ‘proto-modernist’ — the books are also assemblages / collages of diverse and competing sound worlds (pastoral / industrial).

The bucolic frames an often raucous modern core, with Carroll embedding not only catchy anodyne melodies, but also the sounds of the everyday and of contemporary industry, transport, and material culture.

Kiera Vaclavik, ‘Listening to the Alice Books’ (2021)

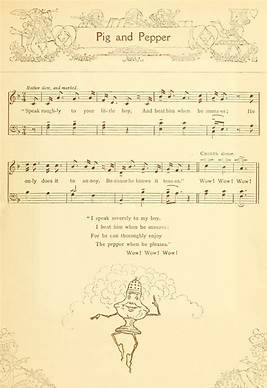

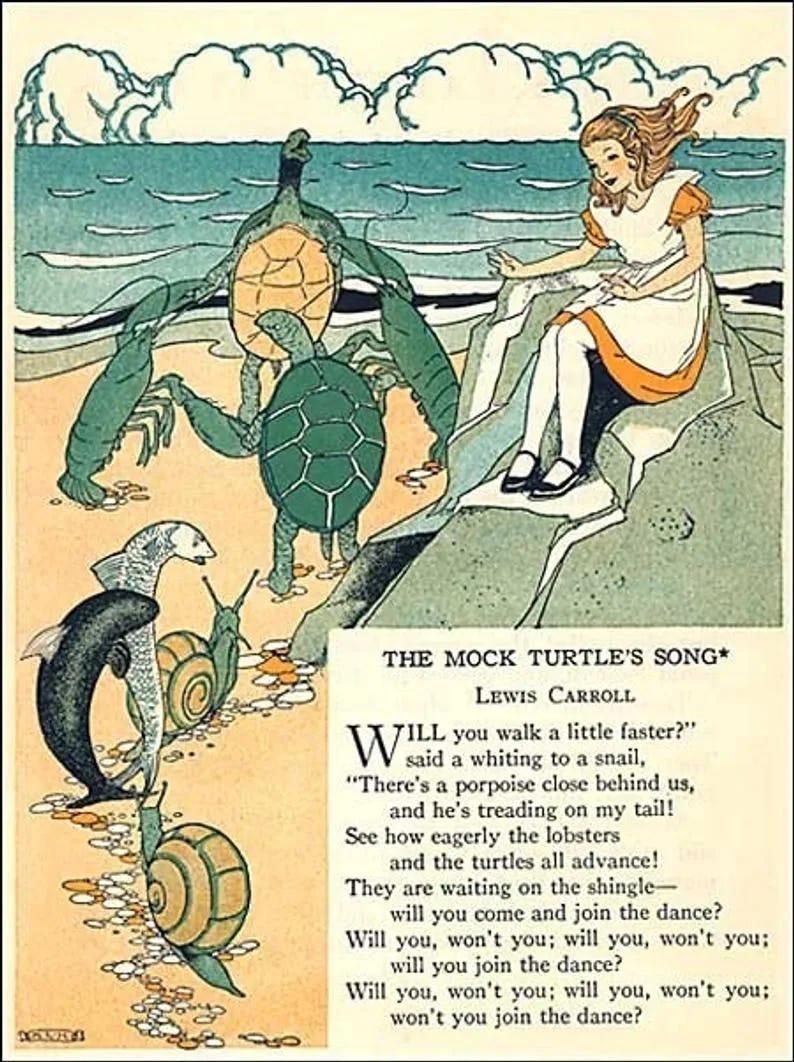

Most obviously, Wonderland is peppered with nursery rhymes and songs - from the ‘Mock Turtle’s Song’ to the ‘Lobster Quadrille’. Rhyme and metre are at the heart of Alice’s journey.

No wonder John and Paul, as hungry, bricolage-obsessed, songwriters, were captivated. Spoiler alert for a later episode: the Mock Turtle is the inspiration for ‘Helter Skelter’s verses (on the White Album):

Will you, won't you want me to make you?

I'm coming down fast, but don't let me break you

Tell me, tell me, tell me the answer!

You may be a lover but you ain't no dancer

These songs live on outside the Alice books. It’s common to find Alice songbooks — settings to music of the “songs” — like this.

Anna Kérchy has a useful reminder too about how children’s texts were consumed, pointing to traditions that must have persisted into the Beatles’ lifetimes, i.e. having Alice read to them, hence performed. Quoting Jan Susina,2 Wonderland is

… ‘a performance-oriented text that begs to be read out loud’, and reminds us that the Alice books in the Victorian era—instead of being read solitarily—were more likely listened to collectively in family reading circles, like that of Mrs George McDonald and her children who enjoyed so much the word- and sound-oriented humour that they eventually convinced Carroll to publish his story for a larger audience (Susina 175).”

-Anna Kérchy, ‘Beau-oootiful Soo-oop! The Magic of Sound and the Melodies of Nonsense in Lewis Carroll’s Wonderland’ (2024).

So I hope it’s clear that the sonority and rhythm of Carroll’s text is inherently musical. Which goes a long way to explaining why John & Paul absorbed and kept gravitating towards the Alice songs.

Of course it would be reductive to imply that it ‘all’ comes from Carroll, and that it all comes directly. It clearly doesn’t. But we saw in a previous post how Carroll influenced surrealism, which in turn, inspired 20th culture, of which The Beatles were of course a part. Just as Flaubert can be seen as a precursor to literary modernism — think of Emma Bovary’s eyes that are sometimes green, sometimes blue — so Carroll is entwined in the shift to cultural, and sonic, modernism.

So let’s time-travel to London in the 60s.

The cultural (and counter-cultural) scene is a vibrant hotbed of cultural experimentation and McCartney, in particular, is lapping it all up. While Lennon had already moved to the suburbs, Paul was making the most of exhibitions, lectures, concerts, happenings:

I used to go to avant-garde music concerts, like. That was me, all that Stockhausen shit in The Beatles. I went to this guy Luciano Berio who’s now an electronic classical kind of guy. It was good, it was a good kind of crossover. A lot of stimulation for me. What Pepper came out of was all of that.

Paul McCartney - The Paul McCartney World Tour Book, (1989).

The most famous (infamous) example of this is probably the atonal orchestral crescendo in ‘A Day In The Life’. The intention — to create a sound like ‘the end of the world’ — was in itself a radical idea, not to mention a pretty unreasonable request. But the execution was also an avant-garde idea — very much in line with Yoko Ono’s instructional artworks — that involved telling the musicians to climb from their lowest to their highest note. It was pretty disconcerting for session musicians of the time, who were used to more structure, and George Martin had to add milestones in to provide an instructional scaffolding. Paul conducted what he called ‘the penguins’.

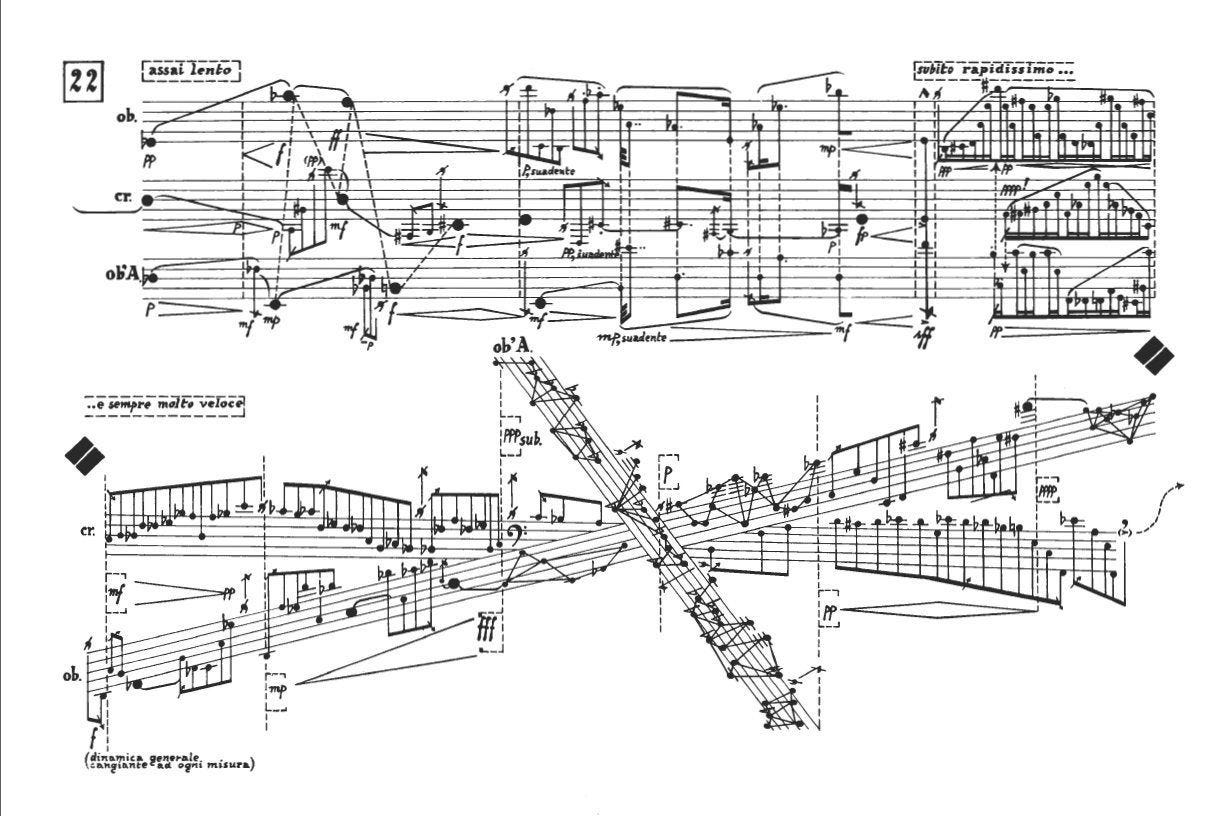

I can’t help seeing a similarity with this Stockhausen ‘graphic score’ and its diagonal throughline:

McCartney’s other inspiration at the time was ‘musique concrète’ and its experiments with recorded sound: collage, tape loops etc.

Here’s a typical set-up, showing just how bizarre and convoluted the technical requirements for this kind of music making were. Today I can do all this on my phone, lying in the bath, but back then it was a hugely expensive and involved, but also engaging, creative process.

This approach would later meet its apotheosis in 1968’s ‘Revolution 9’ — surely the Beatles’ most divisive track (and not just for fans). While John & Yoko were the masterminds of that composition, in 1966 it was Paul’s bag of homemade tape-loops that created the weirdest breakthrough yet. ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ was the first track recorded for Revolver, was the first session with Geoff Emerick in charge, and still stands as one of the most radical adventures in sound.

Ever.

So what are the lessons in all of this? And what do they have to do with Alice?

The real breakthroughs for the Beatles multiplied after they stopped touring, had the run of Abbey Road (since EMI owned the studios), and were liberated from the straitjacket of replicating their studio work on stage. The studio became, for the first time, an instrument in its own right, a play-space where they could lose themselves, and break the rules. It functioned as an alternative reality, cocooned from the real world — full of instruments, tape machines, echo chambers and vast sound effect libraries. There was even a ‘cupboard under the stairs’ full of weird and wacky percussion and then some:

Abbey Road also came with London’s best classical musicians (and a world-class arranger) on tap.

In short, this studio functioned like a portal — to sonic Wonderland.

Now the building itself — even Studio 2 — was a cavernous space, with bleak lighting and few creature comforts. After a while the Beatles came to crave a different, more homely, place to record. But in spite of it all, it was their approach that made the difference. Mindset ultimately matters much more than bricks & mortar.

So I’ve listed 5 mindsets that — I think — got them there, with a little help from Alice and her ‘friends’.

Start before you’re ready (the ‘what if’ / play impulse embodied by the King of Hearts - “start at the beginning and continue until you get to the end: then stop”)

Their mantra of ‘something’ll turn up’; confidence in the end point.

Paul laying down one early-morning take of ‘Oh Darling!’ for weeks until he nailed it.

Combining song fragments (the Abbey Road medley, ‘A Day In The Life’…).

Improvising over fragments (‘You Know My Name, Look Up The Number’).

Searching: anyone recall the ‘humming’ take of ‘A Day In The Life’?

Embracing happy accidents (like the White Knight, who’s always failing happily)

Feedback from semi-hollow guitars (‘I feel Fine’).

Misheard “pass the salt and pepper” becoming “Sgt Pepper”.

The placeholder alarm clock in ‘A Day In The Life’ that stayed in.

Ringo’s screamed “I’ve got blisters on my fingers” (‘Helter Skelter’).

Tuning into the radio and mixing in bits of King Lear (‘I Am The Walrus’).

Never stop morphing (inspired by The Caterpillar’s provocation “who are you?”)

The Beatles are chameleons - their recorded output doesn’t repeat much.

John’s obsession with manipulating his voice to sound not like himself.

Looking outside: to India, to Leary, to the avant-garde, to scream therapy.

Curiosity about studio equipment and determination to abuse it, not respect it.

Do the opposite: a song with a string quartet only? (Hello ‘Eleanor Rigby’).

Reframe everything (inspired by Humpty Dumpty’s ‘words can mean what I make them mean’ approach)

Recording in ‘in-between’ keys (e.g. ‘For No One’).

John’s bricolage: cereal packets and ‘Good Morning, Good Morning’.

The love of ‘nonsense’, that strangely makes more emotional sense.

McCartney’s linguistic inventions, e.g. “butter pie”, “monkberry moon”.

A liking for counter-intuitive paradox (‘Within You Without You’).

Think ‘impossible things’ (like the Red Queen, who claimed to thinking at least 6 regularly before breakfast)… consider all the crazy requests Lennon made:

Putting a microphone into a bag of water (failed!).

Swinging him round the studio on a rope (abandoned in favour of a Leslie speaker - see later!).

Singing lying on his back (on ‘Revolution 1’).

The aforementioned ‘end of the world’ climax to ‘A Day In The Life’.

Splicing together 2 takes at different speeds (‘Strawberry Fields Forever’).

The sound of ‘1,000 Tibetan monks chanting’ (‘Tomorrow Never Knows’).

If these mindsets create a creative Wonderland, Abbey Road facilitated it too, often unintentionally, as the Beatles exploited everything on site, and persistently broke the formal rules that were a legacy of a paternalistic management style. Like Alice, they embodied a lack of respect for authority — George Harrison to George Martin... ‘I don’t like yer tie’ — coupled with a curiosity to peek behind the curtain in search of the new.

But I think the Alice books, and Through the Looking-Glass in particular, contain a formal code, an innovation playbook, or lexicon of experimentation. I believe that The Beatles subconsciously assimilated this code and used it. And I believe that their overt hommages to nonsense, linguistic playfulness, and counter-cultural thematics, were also paralleled in their sonic adventures.

There’s a lot more to catalogue and explore here. I’m indebted to Ryan & Kehew for their exhaustive (and incredibly heavy) tome documenting the Beatles’ recording environment.

In a later post I’ll try to do some data visualisation on the volume of specific effects in their work (count up how many songs use ADT and how many times tapes are reversed, slowed down, or sped up etc).

For now though I just want to create a framework for understanding this “Alice Code” and how it manifests in their studio craft. Have a gander.

Whether it’s subconscious or not, as I’ve said, there are so many similarities in the formal innovations that I think it’s at least worth pointing them out.

What do you think? Do you buy this? Or am I reading too much into it?

While you’re thinking that one through, perhaps we can finish by looking at a few examples to bring my theory to life. I’ll be doing deep dives into key songs in due course, but meanwhile - if you’re not in the know, here are just 3 insights into the technical side of the creative process.

Varispeed

Anyone who heard the Revolver deluxe box set in 2022 was knocked sideways to hear just how fast Ringo is playing on ‘Rain’. In fact it’s the part Ringo’s says is his favourite of everything he’s ever played. And wow, that Paul bassline seems insanely nippy!

But there’s reason in the madness. The objective was to create a drowsy, lazy, trippy feel; playing faster, then slowing the tape down was the way to achieve that. And the electronics? This Levell TG-150m Oscillator, which was also central to the ADT (Automatic Double Tracking) process.

The same trick could be used in reverse, as George Martin explains:

The vocals on ‘Lucy’ weren’t recorded at normal speed. […] we slowed the tape down, so that when we played it back the voice sounded ten per cent higher: back in the correct key, but thinner-sounding, which suited the song. It gave a slightly Mickey Mouse quality to the vocals. […] The second voice track we recorded at forty-eight-and-a-half cycles per second, to see what that sounded like. ‘Lucy’ has more variations of tape speed in it than any other track on the album.

George Martin – From “With A Little Help From My Friends: The Making of Sgt. Pepper”, 1995.

Time and speed are central themes in the Alice books - speeding up, slowing down, rushing, day-dreaming, ‘running to stand still’, are all features of Wonderland, just as they are in The Beatles’ work.

The ‘Leslie’ Speaker

When Lennon demanded to sound like ‘1,000 Tibetan monks chanting’ on ‘Tomorrow Never Knows, ideas included being spun around the studio on a rope. In the end, Geoff Emerick found a safer, and more practical solution, wiring the microphones into a ‘Leslie’ speaker, a rotating device that is how Hammond Organs get their distinctive swirling sound.

Reframing an organ speaker as a vocal effect is disorienting, strange, it changes the feel and sense of scale - in a very Alice like way - because it does something neuroaesthetic to our sense of place and reality.

Reversed sounds

Through The Looking-Glass foregrounds mirroring and reversal, topsy-turvyness, with the visual metaphor of the chessboard a potent symbol. But inversion is everywhere in Wonderland, from all the ways rules and norms are turned on their heads, to physical inversions (tumbling, falling, losing direction).

Lennon seemingly discovered reverse effects when he simply loaded up a home tape the wrong way round — perhaps stoned — and it’s what inspired one of the first Beatles backwards passages (a vocal on ‘Rain’), closely followed by the backwards guitar solo on ‘I’m Only Sleeping’.

‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ uses some of the Taxman guitar solo run backwards, while as time went on, reverse effects became more and more ubiquitous and subtle, showing up on vocals, percussion, cymbals, sound effects and more - particularly in the 67/8 work (Sgt Pepper, Magical Mystery Tour, Yellow Submarine, parts of The Beatles (White Album).

We’ll return to all of this as we begin to dive into some of the very most iconic Alice-inspired songs. Let me know if you have favourites you want to know more about, and I can do some extra digging…

Next time…

In episode 8 I have another exclusive interview for you. This time with Andy Maxwell, an ex-Abbey Road engineer who’s part of the Beatles remixes team (think Red & Blue Albums from last year).

We talk about creativity, freedom, the notion of play, Abbey Road as a creative space, technological experimentation and some of the more psychedelic songs, and how they create ‘aural’ Wonderland.

I really enjoyed speaking to him — with our top psychedelic picks (from ‘Flying’ to ‘Magical Mystery Tour’ to ‘I am the Walrus’) playing in the background — and I hope you’ll enjoy reading it just as much.

See you next week!

Sources:

Nick Coates & Ned Colville, ‘The Alice Code: Looking-Glass Thinking for Innovators’ in Through the Looking-Glass: A Companion (Houyaux & Kohlt (eds.) 2024)

Geoff Emerick, Here There and Everywhere (2006).

Anna Kérchy, ‘Beau-oootiful Soo-oop! The Magic of Sound and the Melodies of Nonsense in Lewis Carroll’s Wonderland’, Cahiers Victoriens et édouardiens, Autumn 2024.

Mark Lewisohn, The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions: The Official Story of the Abbey Road Years 1962-1970 (1988).

George Martin, All You Need is Ears (1979).

Kevin Ryan & Brian Kehew, Recording The Beatles: The Studio Equipment and Techniques Used To Create Their Classic Albums (2006)

Kiera Vaclavik, ‘Listening to the Alice Books’, Journal of Victorian Culture (2021).

Vaclavik, ‘Listening to the Alice Books’, Journal of Victorian Culture, 2021, Vol. 26, No. 1, 1–20.

English Professor at Illinois State University and author of The Place of Lewis Carroll in Children's Literature.

fabulous details! oh, and did I mention the Andrew Hickey podcast episode ... 🤣