“In our mind it was an Alice thing, which both of us loved” - Paul.

Each week on this blog we trace the mycelium-like web of connections between mid-19th C. Lewis Carroll and The Beatles, 100 years later.

Last week I outlined 7 connection points in Sgt Pepper. Today, I’d love you to follow me down to a bridge by a fountain, for a deep-dive into the most Carrollian song on the record. Why not have a listen while you read:

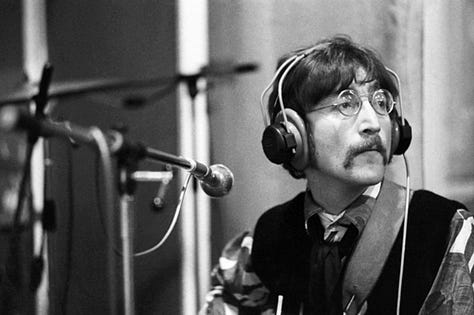

Rehearsals for ‘Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds’ started recording at Abbey Road on February 28th 1967 with George Martin surveying proceedings, but the inspiration starts long before…

‘Lucy’ is a song that’s been hotly debated — ever since Sgt Pepper was released and the BBC banned the song — because of the purported LSD allusions. But focusing on this is deeply reductive. It’s ignoring the much more interesting aspects of the song, and that’s what I’ll focus on here, especially the lyrical, visual and metaphysical links back to Alice.

Of course there is no doubt that LSD played a role in The Beatles psychedelic imagination, but the insistence that it was encoded in the title (L.S.D.) has become tiresome (to me at least — let me know what you think, dear readers).

Lennon both denies the intent,1 and has a better, and much more interesting explanation. It all starts with 4-year old Julian Lennon’s drawing:

Julian drew his friend Lucy O’Donnell, at nursery. Once home he explained the images to his Dad: ‘it’s Lucy, in the sky, with diamonds’. John was immediately captivated and — without delay, he claims — set out to turn it into a song.

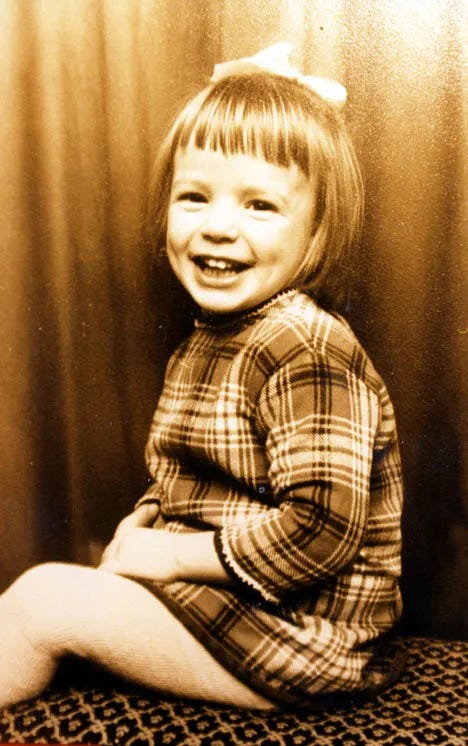

While there’s a ‘real’ person behind the drawing, it’s the symbolic Lucy I’m most interested in. But perhaps seeing the ‘real’ Lucy will help bolster the idea that it’s not L for Lysergic. So here she is:

However, beyond the brilliantly surreal imagery in Julian’s drawing, which provides the song’s refrain, the real lyrical inspiration is Lewis Carroll, and some specific scenes in Through The Looking-Glass.

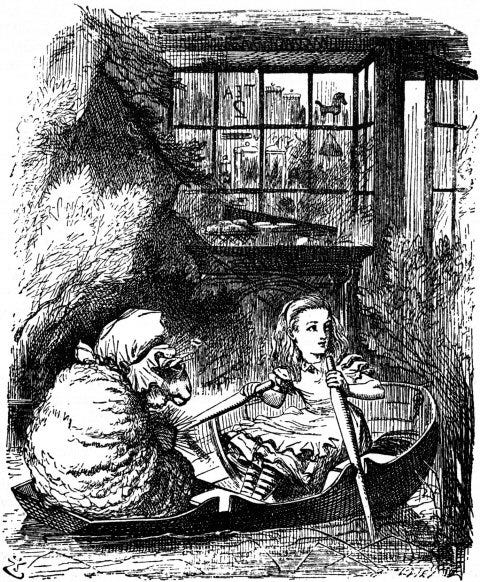

The images were from Alice In Wonderland.2 It was Alice in the boat. She is buying an egg and it turns into Humpty Dumpty. The woman serving in the shop turns into a sheep, and the next minute they’re rowing in a rowing boat somewhere—and I was visualizing that.

-John Lennon, Playboy Interview (1980)3

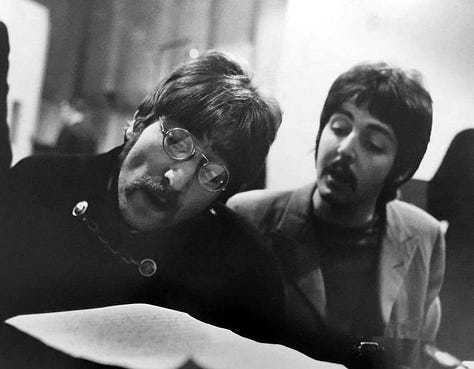

Paul also reminds us how Carroll’s freedom with language, and the invitation to imagination, became the intentional touchstone here:

It started off very Alice in Wonderland: ‘Picture yourself in a boat, on a river … It’s very Alice. Both of us had read the Alice books and always referred to them, we were always talking about ‘Jabberwocky’ and we knew those more than any other books really […] I sat there and wrote it with him: I offered ‘cellophane flowers’ and ‘newspaper taxis’ and John replied with ‘kaleidoscope eyes’. I remember which was which because we traded words off each other, as we always did … And in our mind it was an Alice thing, which both of us loved.

Paul McCartney – From “Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now” by Barry Miles, 1997

So let’s take a closer look at the language and lyrics of Lucy, which is stuffed full of Alice-type images and words.

I’m really struck by the 3-verse structure, since each manifests a different location in the dreamworld, and each recalls scenes from the Alice books.

V1

‘Picture yourself in a boat on a river’…

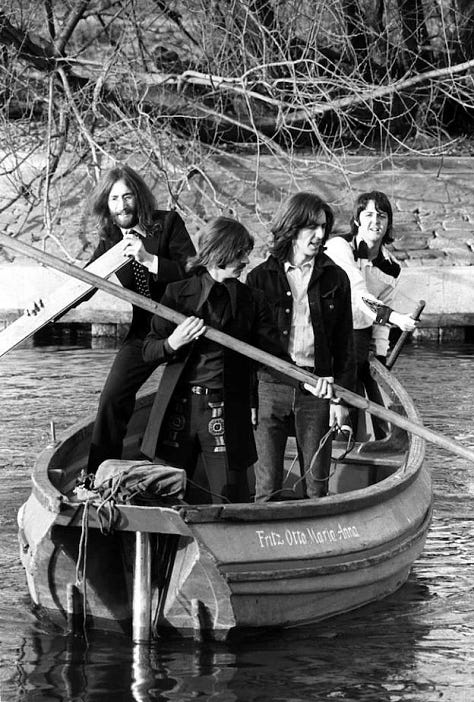

There’s a very English, pastoral, quality to rowing boats. A feature of Victorian parks, pastimes,4 as well as children’s stories — not least The Wind In The Willows — the Beatles were no strangers to “messing about in boats”.

Aquatic imagery is often a cipher for the subconscious, even amniotic fluid in a pre-conscious sense, and the river definitely echoes that, picking up on ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ and the appeal to ‘relax and float downstream’.

But this is also a direct allusion to the ‘Wool & Water’ chapter of Through the Looking-Glass where — as John mentioned — the White Queen has turned into a sheep who starts knitting and then the knitting needles become oars…

‘Can you row?’ the Sheep asked, handing her a pair of knitting-needles as she spoke.

‘Yes, a little—but not on land—and not with needles—’ Alice was beginning to say, when suddenly the needles turned into oars in her hands, and she found they were in a little boat, gliding along between banks: so there was nothing for it but to do her best.

-Lewis Carroll, Through The Looking-Glass (1871)

I love this image because it’s one of the Tenniel illustrations that best shows the idea of transformation, and the shifting between scenes that’s so central to dream narrative:

V2

‘Follow her down to a bridge by a fountain’…

While I haven’t tracked down many bridges in Wonderland, the imagery of verse 2 feels reminiscent of the magical garden Alice stumbles into, with its flowers and ‘cool fountains’:

Alice opened the door and found that it led into a small passage, not much larger than a rat-hole: she knelt down and looked along the passage into the loveliest garden you ever saw. How she longed to get out of that dark hall, and wander about among those beds of bright flowers and those cool fountains

-Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865)

I can’t help thinking “the flowers / that grow so incredibly high” in Lucy are inspired by the flora in Wonderland, and are also part of the Beatles’ visual lexicon, like this shot of the Beatles on their “mad day out”, dwarfed by hollyhocks.

V3

‘Picture yourself on a train in a station’…

In the chapter ‘Looking-Glass Insects’, from Carroll’s sequel to Alice in Wonderland, our heroine finds herself in a train carriage, being by turns berated by a guard for not having a ticket, then for “travelling the wrong way”, and then pestered by insects whispering in her ear. Here we see the guard looking at her through opera-glasses:

It makes a lot of sense, given this, that the ‘plasticine porters’ in Lucy, are wearing ‘looking-glass ties', and also that there are rocking-horse people in the previous verse, given that some of the insects are portmanteaus & puns, like “rocking-horse flies”.

The lyrical parallels don’t end there.5 I’ve picked out a few more for your delectation:

Skies is quite an unusual and poetic version of the more common ‘sky’; it puts me in mind of Carroll’s “Alice moving under skies, never seen by waking eyes”,6 not to mention McCartney’s ‘Calico Skies’ from Flaming Pie (1997).

These skies aren’t any old colour, they’re marmelade: while falling down the rabbit hole, Alice grabs a jar marked “ORANGE MARMELADE”.7

The repeated mention of eyes reminds me of the reference to “dreaming eyes of wonder!” from the poem that’s a prelude to Through The Looking-Glass.8

It’s a stylistic homage, no doubt, but there’s more, and this is where I think the LSD piece is reductive. Lucy isn’t just Julian’s nursery friend, she’s an archetype. Paul and John have different takes, but both emphasise her symbolic quality.

For Paul, Lucy “was God, the Big Figure, the White Rabbit”, a mysterious figure and guide; for John it was the repeated ‘saviour’ figure we see in songs like Julia (with her ‘seashell eyes’):

There was also the image of the female who would someday come save me—‘a girl with kaleidoscope eyes’ who came out of the sky.”

-John Lennon, 1980

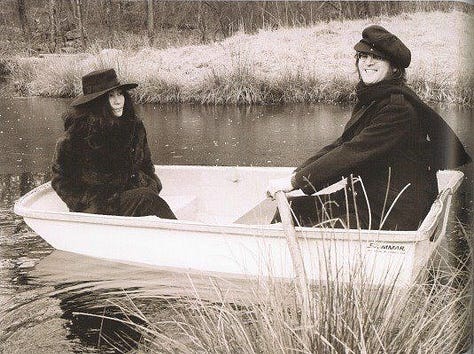

Lennon seemed to be always searching for something slightly out of reach. Yoko became his saviour, his Lucy. Perhaps if Lucy is White Rabbit guide, then it’s John who’s casting himself as Alice-like adventurer, dreamchild.

The song’s mystical, seeking, starry-eyed, quality is another layer on top of the usual LSD narratives. It links the personal and the public realm; The Beatles enshrining in song a moment of psychedelic awakening and questioning, with a quality of hope and awe. As Nicholas Schaffner puts it, the song perfectly encapsulates how "young people were trying to transcend, transform, or escape from straight society" in 1967.9

I’ve spent most of this blog focusing on language and narrative. But of course Lucy is a production breakthrough as well. The harmonic structure, modulating between 3 keys (A, Bb and G) is unusual for its period; when coupled with the alternating 3/4 and 4/4 sections, these shifts definitely add to the surreal atmosphere of the song.

And it’s the sonic touches that really elevate the track.

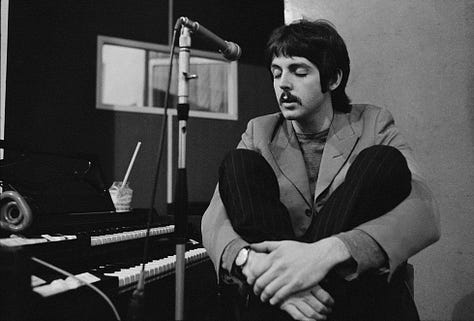

Paul’s looping opening figure, with its use of the Lowrey organ (see above, behind Paul), is masterful — strangely reminiscent of a music box. It outlines the verse chords in the least boring way possible (another triumph in the manner of ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’).

Meanwhile George’s droning Tanpura provides the stable cosmic core for Paul’s rotating melody. ADT, Leslie cabinet effects, and heavy reverb seem slathered on, and wrap the musical lines in a kind of aural glitter. ADT is so much more than a doubling technology; because of the way it works — using oscillators — it has a subtle ‘sucking’ feel, with elements of the sound coming and going and ending up ‘tricking the brain’, as Andy Maxwell so accurately pointed out in our interview last week.

George Martin has also said that Lucy used more ‘vari-speed’ that any other track on Sgt Pepper, and the ‘Mickey Mouse’ / helium balloon effect is there on lead and backing vocals. I assume that’s the reason I didn’t recognise the Beatles voices I thought I knew — as a child — and part of the secret behind its otherworldly feeling.

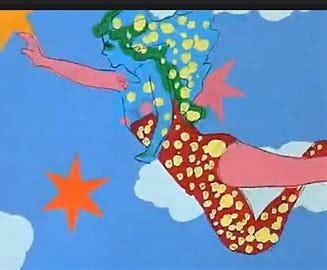

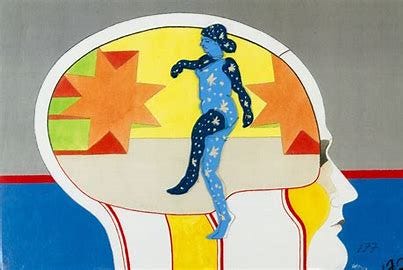

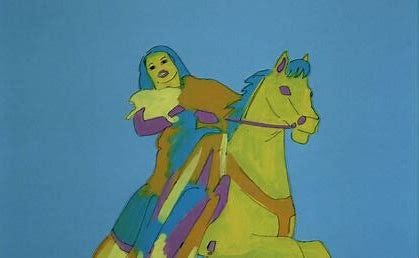

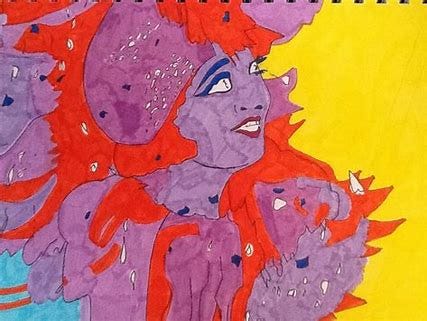

Mystical vision. Psychedelic anthem. Literary homage. Saviour narrative. That the song contains these layers is — I think — a mark of its enduring fascination and standout quality. The song went on to feature in 1969’s animated Beatles movie, Yellow Submarine. If you have time, check out the rather wonderful rotoscoping and dance sequences.10

If not, then just feast your eyes on some of the stills.

That’s my fill of colour for the week.

See you next time, for another big one: ‘I Am The Walrus’.

[And don’t forget to hit subscribe below if you want to be notified when it’s out]

Paul too: “People later thought ‘Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds’ was LSD. I swear we didn’t notice that when it came out, in actual fact, if you want to be pedantic you’d have to say it is LITSWD, but of course LSD is a better story.” Paul McCartney – From “Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now” by Barry Miles, 1997

The fact that John often mistakes which book is being referred to — i.e. it’s actually Through The Looking-Glass — is just a reminder of the bricolage brain and part of my willingness to be less literal about some of the intertextual allusions. It’s clear to me that much of the imagery has wormed its way, mixed up as it is, into John’s imaginary.

NATURE: tangerine trees, marmelade skies, cellophane flowers

PEOPLE: plasticine porters, kaleidoscope eyes, rocking-horse people

THINGS: marshmallow pies, looking-glass ties, newspaper taxis

Lewis Carroll, ‘A Boat Beneath A Sunny Sky’.

“She took down a jar from one of the shelves as she passed; it was labelled “ORANGE MARMALADE”, but to her great disappointment it was empty: she did not like to drop the jar for fear of killing somebody underneath, so managed to put it into one of the cupboards as she fell past it.”, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, chapter 1 (‘Down The Rabbit Hole’).

“Child of the pure unclouded brow

And dreaming eyes of wonder!

Though time be fleet, and I and thou

Are half a life asunder,

Thy loving smile will surely hail

The love-gift of a fairy-tale.”

Through The Looking-Glass (1871)

The Beatles Forever, 1977.

For the most scholarly and in-depth background & commentary: Animation History: The Films Behind that famous Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds sequence!

wonderful chapter in the story - outstanding! I love the musical analysis too - appreciating it must be harder to do in writing vs aurally