11 The Walrus & The Songwriter

Lennon sets out to defy the analysts with peak Jabber-rocky nonsense.

Get ready for a linguistic and sonic kaleidoscope that was also Lennon throwing down the gauntlet: “let the fuckers work that one out, Pete!”.

Curious to learn more? Let’s go!

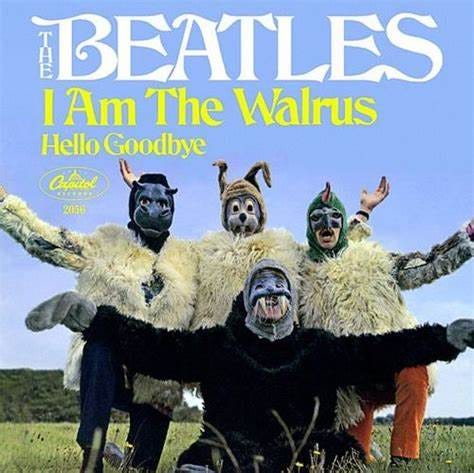

Each week in Alice & The Eggmen I trace the subtle connections between Lewis Carroll, the Alice books and The Beatles. Today we tackle one of the most talked-about tracks — ‘I Am The Walrus’ — a song that Lennon himself says is inspired (partly at least) by Lewis Carroll’s ‘The Walrus & The Carpenter’.

I’d struggle to pick a single desert island Beatles song, but more often than not ‘Walrus’ is on my shortlist. Why? There’s just so much to love, so much going on, everywhere you look.

In this post we’ll cover word games, egg games, brain trickery, modernism and post-modernism, found sounds, down-and-up sounds, Jabber-rockery, and much more.

Why not click on the link to play it, while you read on…

It all starts with a siren.

A police siren.

Nee-naw nee-naw nee-naw nee-naw.

Heard by Lennon out of his window one day, a passing police vehicle, siren going, triggers ‘little policemen’ imagery, but also the basic musical motif.

It’s the song’s opening rhythm, a rocking back-and-forth on the keyboard, a strong accent on each beat in the bar, underneath a softly repeated upper note, that creates a kind of almost imperceptible drone. It’s a 21st Century version of the bagpipes, or a hurdy-gurdy, getting going, and sets the scene for what’s to come.

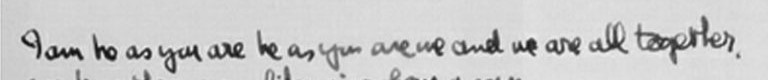

And now the descent, a series of falling tones - B to A to G to F to E to D… - ‘take us down’ an unexpected chordal staircase that subverts convention, before settling to prepare the way for John’s opening salvo, a gnomic statement that’s quintessential Alice:

Some claim inspiration from ‘Marching to Pretoria’1 (“I’ll walk with you, you walk with me, and / So we will walk together); and that may well be an influence, though I’ve seen no proof of it.

Walter Everett, in The Beatles as Musicians,2 wonders whether it’s not a nod to Alice’s identity crisis when she wonders whether she’s turned into her sister Mabel: “Besides, she’s she, and I’m I, and—oh dear, how puzzling it all is!”.

The erasure of ego common to — and sought by — LSD users also comes to mind. Given that John says that the first line was written on a trip one weekend, that’s also a clear contender.

The first line was written on one acid trip one weekend, the second line on another acid trip the next weekend, and it was filled in after I met Yoko.

-John Lennon, 1980, All We Are Saying, David Sheff

IDENTITY GAMES

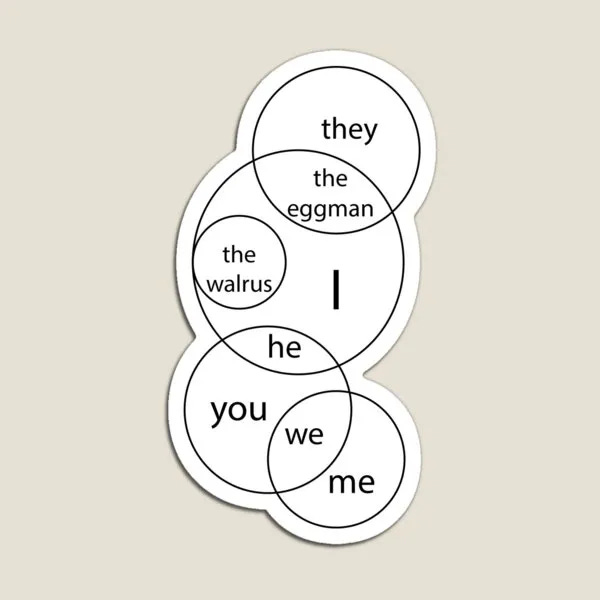

Of course the reality will be somewhere in between, an assemblage of unconscious fragments, that LSD unlocked. Ultimately it’s an identity puzzle, and I can’t resist sharing the venn diagram that I have on a t-shirt, and is also available as a fridge magnet if you’re that way inclined.

Either way, it’s a big shift. In its slithery view of identity, the early Beatles pronominal binarisms are erased. It’s goodbye “From Me to You”, “Please Please Me”, or “PS I Love You” — simplistic girl-boy love stories — and hello to multiple and interchangeable identities.

John’s melody is also an insistent siren, reminiscent of a Muezzin call or perhaps a Tibetan monk’s chant. I’m never quite sure whether it’s a repeated tone, a semitonal or microtonal back-and-forth, but I think the reality is a blend of all of the above. It’s insidiously indeterminate, an ear-worm that demands attention, but never settles.

Until it reaches its pseudo-conclusion:

I am the eggman,

They are the eggmen,

I am the Walrus.

Eggmen, you say?

The egg-man feels like a clear nod to Humpty Dumpty, the original eggman (and yes - there are also those who like to cite Eric Burdon, of the Animals, and his predeliction for sexual acts involving the cracking of eggs). And aren’t we all eggmen? Defiers of logic? Wielders of words? Playful protagonists? Restless riddlers?

Sure, but what about the Walrus?

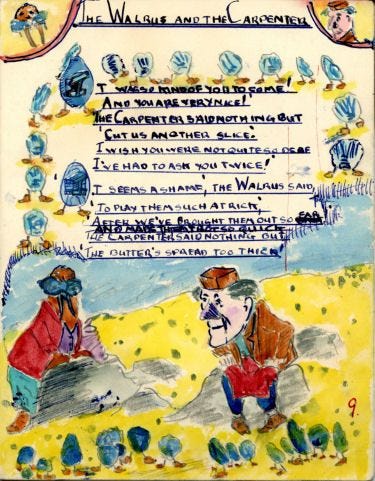

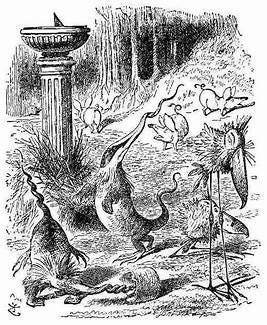

This is a blog about Lewis Carroll, and the Alice books were John’s childhood rosetta stone, something he returned to constantly over his life. And of course there’s a Walrus in Through The Looking-Glass, in the shape of oyster guzzling duo ‘The Walrus And The Carpenter’.

And this is one of the scenes that John drew faithfully in his school sketchbook:

But clearly Walruses are a red herring (mixed metaphor intended). John’s lyrics don’t refer to the narrative of Carroll’s poem itself - the subject matter is irrelevant; and indeed - later in life - John said that he hadn’t even understood it properly, he just thought it ‘beautiful’.

And it really is! Carroll’s poem shimmers in its juxtaposition of unexpected imagery:

“The time has come,” the Walrus said,

“To talk of many things:

Of shoes—and ships—and sealing-wax—

Of cabbages—and kings—

And why the sea is boiling hot—

And whether pigs have wings.”-Lewis Carroll, ‘The Walrus And The Carpenter’, Through The Looking-Glass (1871)

But this isn’t where Walrus stops.

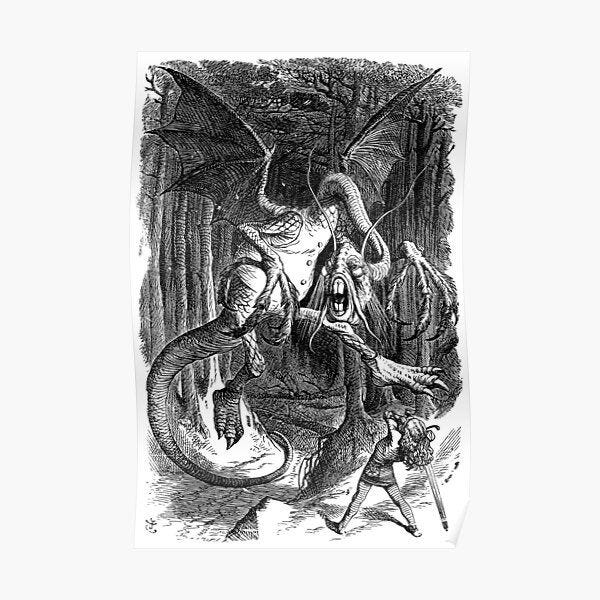

BEWARE THE JABBERWOCK

As we’ve said previously, John & Paul always connected Carroll’s wordplay with ‘Jabberwocky’, through the use of nonsense, neologisms, portmanteaus and puns. It’s a poem that was magical and liberating to both of them, a poem they “were always talking about”, a kind of creative licence to use language without limits.

The infamous opening, “‘twas brillig, and the slithy toves, did gyre and gimble in the wabe”, is already echoed in John’s early 1960s writing, beginning with In His Own Write, a book which I opened randomly for this blog to find passages to share. Like this one:

Rephy graun and gratty

Graddie large but smail

She will not brant a fatty

Room to swig a snail-John Lennon, from ‘On This Charly Morn’, In His Own Write (1964)

Walrus is a linguistic as well as a sonic kaleidoscope; a feast of linguistic invention: “crabalocker fishwife”, “semolina pilchard”, “elementary penguin”, “goo goo g’joob”, “see how they snied”. But even these fragments of apparent nonsense — like ‘Jabberwocky’ — contain linguistic and emotional meaning. In a way that I think would have delighted fellow bricolage enthusiast Carroll — Walrus weaves these into a tapestry of sources, ideas, allusions, alliterations, and quotes…

-A schoolyard chant (“yellow matter custard…”).3

-Nursery rhymes (“see how they fly” / "see how they run”).

-Snide socio-cultural comments (the “elementary penguin”…)

-Echoes of Carroll’s “Jub-Jub birds” in “goo goo g’joob”?4

-Snippets of King Lear from the radio (“a serviceable villain”)

-Self-referential misdirection (‘like Lucy In the Sky’)

FROM PLAY POP TO PUZZLES

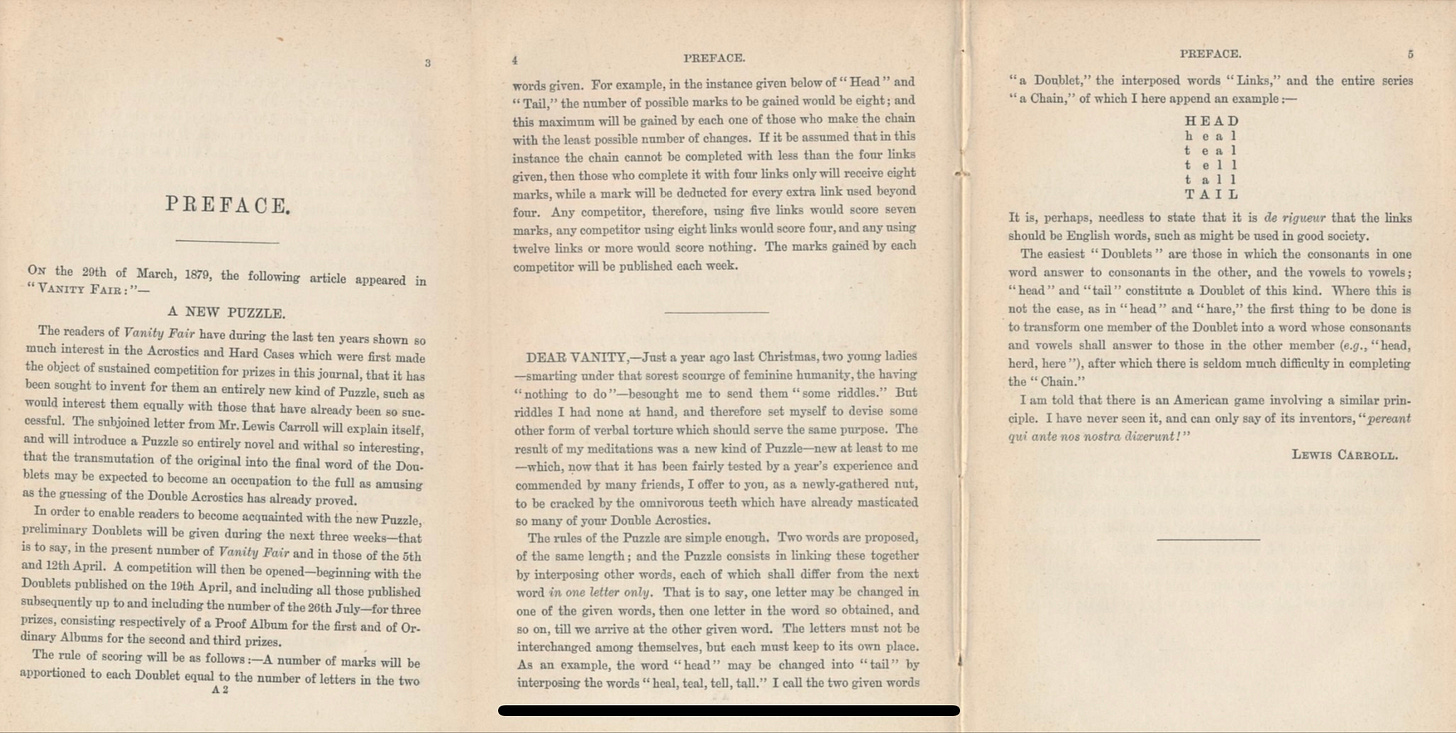

Some commentators have also pointed to lines like “expert, texpert, choking, smokers” as evidence that Carroll’s puzzles and games were another influence, in the form of ‘word ladders’ or ‘doublets’:

I’m grateful to Mark Russell-Richards for an exchange about the distinction between two Carrollian inventions: “word ladders” and Syzygies. (If you’re wordplay minded, you might enjoy this ‘doublet’ puzzle solver).

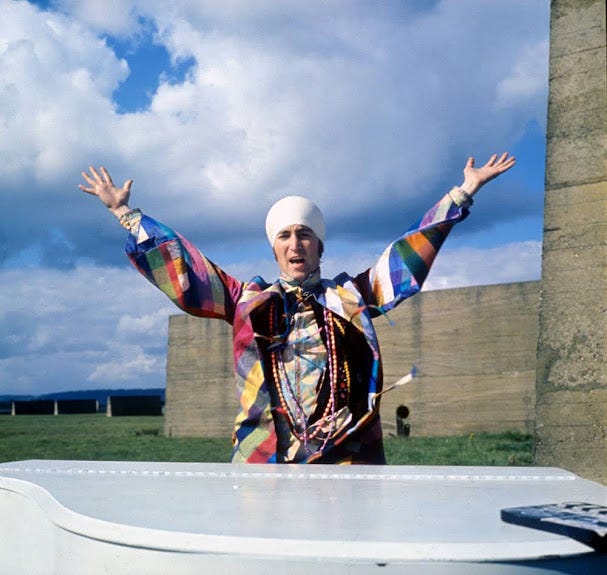

As so often with The Beatles, it’s process and poetry — as much as characters and imagery — that become the creative touchstone. Carrol’s linguistic games, and taste for anthropomorphism are hiding in plain sight, inspiring the costumes we see on the single cover and in Magical Mystery Tour:

FOILING THE FUCKERS

What is this fabulous tapestry if not the Beatles’ richest, trippiest, manifestation of Jabberwocky playfulness, ‘dripping with’ not just “yellow matter custard” but also visceral, vituperative, disdain for reduction, for over-interpretation?

Alice herself dramatises this tension, when she reacts to ‘Jabberwocky’:

“It seems very pretty,” she said when she had finished it, “but it’s rather hard to understand!” (You see she didn’t like to confess, even to herself, that she couldn’t make it out at all.) “Somehow it seems to fill my head with ideas—only I don’t exactly know what they are!”

—Alice, upon first reading “Jabberwocky” in Through the Looking-Glass (1871)

I don’t think Lennon read Barthes at the time (though I also have no proof to the contrary), but I like to remind myself that I Am The Walrus and The Death of the Author both saw the light of day in November 1967. What a month.

And whether there’s a conscious connection is immaterial. The truth is that both were swimming in the same counter-cultural waters. When John discovered that students at his alma mater, Quarry Bank, were analysing his songs, it motivated him to throw them off the scent.

"One afternoon, while taking "lucky dips" into the day's sack of fan mail, John, much to both our amusement, chanced to pull out a letter from a student at Quarry Bank. Following the usual expressions of adoration, this lad revealed that his literature master was playing Beatles songs in class; after the boys all took their turns analyzing the lyrics, the teacher would weigh in with his own interpretation of what the Beatles were really talking about. (This, of course, was the same institution of learning whose headmaster had summed up young Lennon's prospects with the words: "This boy is bound to fail.")

-Pete Shotton, John Lennon In My Life, 1983, Stein and Day.

I’ve always found it ironic that critics who repeat this story — as though it explains everything — fail to see how this in itself constitutes an act of reductive interpretation that negates the layers in Walrus. Of course, Lennon always loved a good “take this then”, but Walrus is so much more than a V-sign to the critics.

It’s not nihilism, it’s pluralism.

Walrus - it seems to me - actively embraces multiplicity of meaning, it’s a tapestry not a wall. And maybe importantly, for all those critics out there who don’t get how art works, it’s replete and rich with emotional signifiers, that speak louder than conventional description. I’m convinced he would have hated seeing it as anything else.

WALRUS TONES

And so, back to the music. Ian MacDonald has called Walrus…

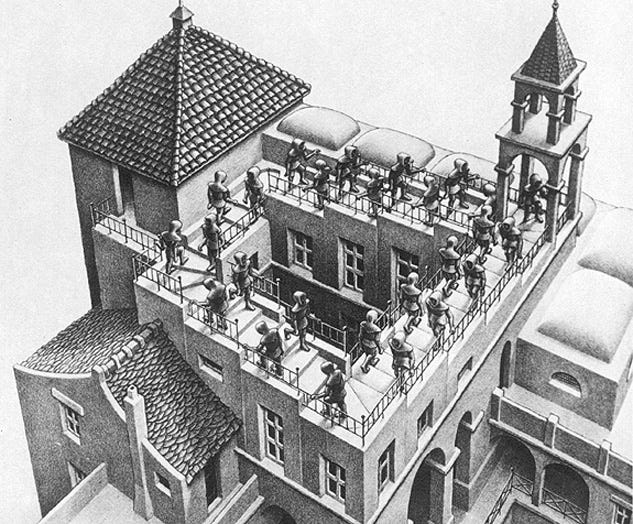

“The most unorthodox and tonally ambiguous sequence he ever devised […] an obsessive musical structure built round a perpetually ascending/descending MC Escher staircase of all the natural major chords”.

-Ian MacDonald, Revolution In The Head

Descending and rising chords should be a familiar idea that parallels the descent/return to underworld themes embedded in the Alice books.

But The Beatles go one step further. As the song reaches its cataclysmic conclusion we hear the descent paralleled with a rising line in the strings, creating an aural illusion that musicologists refer to as ‘Shepherd Tones’. A downwards and upwards melody / bassline trick the brain into hearing a constantly rising pattern, much like Escher’s Ascending and Descending:

It’s crazily modern, and compounded by the sonic collage that includes snippets of a BBC radio production of King Lear that was randomly flown into the final mix. No wonder that subsequent interpreters have leant into its modernity. The person, I think, who has best understood and adapted Lennon’s harmonic language is Brad Mehdlau, on 2024’s Beatles tribute album Your Mother Should Know:

And so I guess it’s worth a visual recap, putting it all back together again. Check out the video, a sequence from Magical Mystery Tour:

Bricolage: Siren | Walrus & The Carpenter | Humpty Dumpty / Burdon | Hari Krishna | Schoolyard chants | Nursery rhymes | Nonsense | Jabberwocky | King Lear

Thanks for reading this far.

See you next time.

The Beatles as Musicians: The Quarry Men through Rubber Soul, OUP, 2001.

…and foreshadow Come Together’s “joo-joo eyeball” two years later.

"It’s not nihilism, it’s pluralism" - very nice!

creativity and cussedness - a bit of everythingness

as is BM's rendition of IATW btw

very enjoyable chapter!

Any mention of Escher and music and I think of that Everest of a book which is Hofstadter’s masterpiece. Love your serie - great reads