33 Crackerbox Crisp

Friar Park and Sir Frankie Crisp - part Carroll, part Disney.

Every week on Alice & The Eggmen, we trace the better and lesser known points of connection between the 1860s and 1960s, between Lewis Carroll, the Alice books, and the work of the Beatles.

If you haven’t already, do consider subscribing for updates:

This week we’re looking at George Harrison, and his Friar Park home.

Of all the fabs, George is the one with the fewest overt Wonderland traits.

That doesn’t mean there’s nothing going on, of course. As we’ve mentioned:

He played guitar on The Hunting of The Snark (the Mike Batt version).

His song ‘Any Road’ is the source of the most misquoted Alicism: “if you don’t know where you’re going, any road will get you there” (likely inspired by Carroll, just reformulated).

His music for Wonderwall drives a film inspired by the Fool’s painted armoire (that’s Carrollian in spirit) and his friend and mentor Ravi Shankar ended up scoring Jonathan Miller’s Alice.

So there are links, for sure. But generally it’s much more John & Paul who leant into Jabberwocky writing and Alice imagery. And it’s Ringo who brought hattery to life for Marc Bolan on Born to Boogie and played the Mock Turtle on TV.

George, by contrast, swims in slightly adjacent waters; he’s more explicitly a fan of Monty Python, George Formby, Indian music and spirituality. We don’t (often) find him talking about Lewis Carroll openly. In many ways he’s Alice-adjacent more than Alice-infused.

Which is why I’ve become curious about his incredible love story with Friar Park, a place he, as well as many others, have likened to a Lewis Carroll world. So let’s take a closer look.

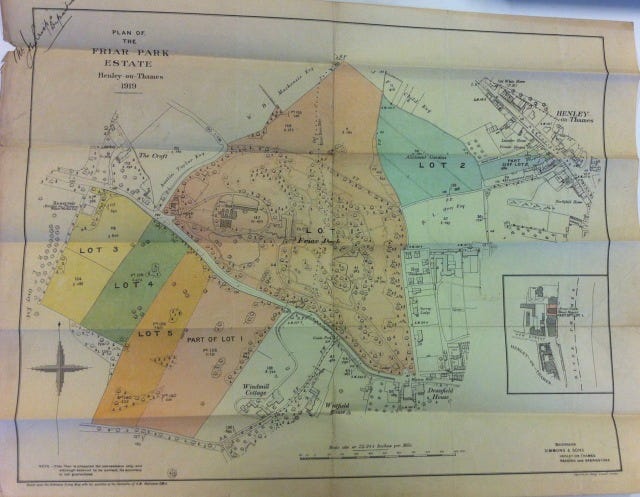

Friar Park is a sprawling estate in Henley-on-Thames, still owned by the Harrisons, and a place George came to love, partly because of its secluded location, partly because it allowed him space to build a fabulous studio where he could work in peace, but largely because of the fantastical conception that sprang from the imagination of Sir Frankie Crisp, about which George penned a song:

Fools illusions everywhere

Joan and Molly sweeps the stairs

Eyes are shining full of inner light

Let it roll into the night-George Harrison, ‘Ballad of Sir Frankie Crisp’

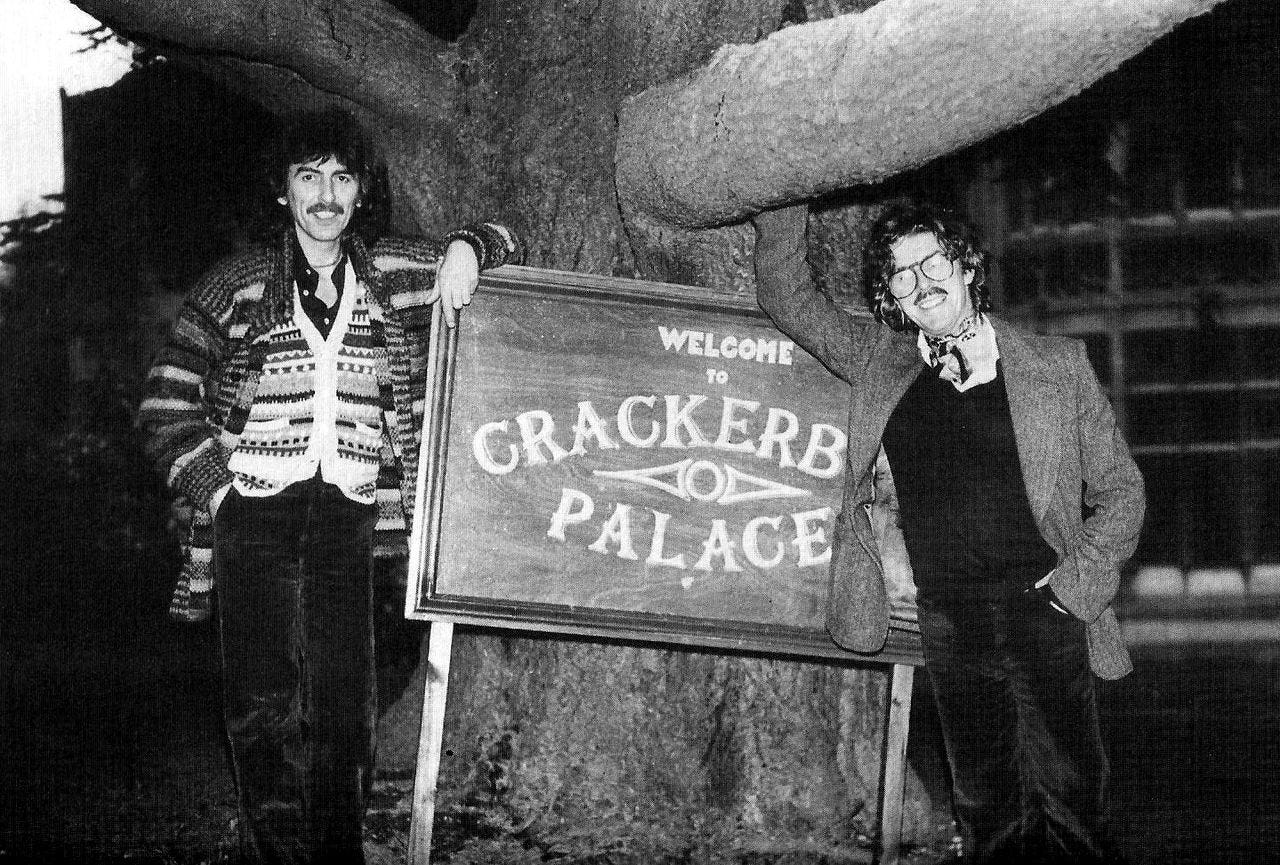

Later, inspired by a throwaway comment by a friend, he picked up on the phrase ‘Crackerbox Palace’, wrote it down on a cigarette packet, and used it as a nickname for the place, with an accompanying, surreal, video:

With its cast of curios, human gnomes and eccentric tea parties, the video certainly evokes the spirit of Carroll, if not the letter.

There’s no evidence that Crisp and Carroll knew each other, or that Wonderland was an inspiration either for the design, or for ‘whimsical’ features like the “don’t keep off the grass” signs, but Friar Park was developed in 1889, well after both the Alice books, and I think we can assume that Crisp would have known of Wonderland. It’s even more likely that the Victorian fascination with follies, exotica, optical trickery, mirrors and fairies would have been part of a common culture he drew on.

One of the mock medieval maps, perhaps more Tolkien than Carroll on the surface, nonetheless reveals a distinctive and satirical sense of humour with its ‘vallie of daffodowndillies’ and ‘gloomie glenne’:

The notion of a looking-glass world, with anthropomorphic characters, living objects, and fantasmagorical transformation, brings us onto more common ground.

It’s not just me dreaming it either. Many commentators have made the connection, not least Monty Don in his documentary about the gardens:

“Crisp, like many Victorians, had a passion for alpine plants, so he built himself a rockery, except he did it on an heroic scale. He had no less than 23,000 tons of Yorkshire stone brought into the site. First to Henley railway station and from there by horse and cart. Each stone was carefully placed one by one to make, what was then, Britain’s largest rock garden.

Clearly Frank Crisp loved creating this though the looking-glass surreal world and certainly George and Olivia have had fun in restoring it and making it their own.”

-Monty Don, Monty Don’s British Gardens

You can watch the fascinating tour here:

A particular feature that clearly tickled George’s imagination was the discovery of a network of underground grottoes, reached by a hidden river:

“The parkland, open to the public during Crisp’s lifetime and long after his death in 1919, was a cross between Botanical garden, fairground attraction and Lewis Carroll’s Wonderland […] There was a series of man-made underground caves and grottos through which one could travel by boat from one lake to another, the journey enlivened by distorting circus mirrors, gnomes, fairies, toadstools and shimmering blue glass.”1

Dan Pearson reports on the boat trip he took with Olivia to the grottoes:

“Before I left, Olivia took me on a magical tour in the rowing boat under the lake. We entered a cleft in the rocks alongside the waterfall that splits the two levels and paddled our way behind the cascade. Light bounced off the stucco walls as we entered the tunnel, but before long we had left the roar and the light behind and were paddling through the pitch-black. I began to wonder how far we could feel our way into the darkness but rounding a corner the shimmering grotto was revealed. Blue glass panels set into the garden above let an eerie light fall over the columns of spa stone that rose from the water. As we floated through this mysterious inner landscape, I had to pinch myself that I was really there and part of the fantasy.”

-Dan Pearson, ‘Magical Mystery Tour’, The Guardian, 2008.2

So others have made the connection — Friar Park as Wonderland dreamworld — but what about George? Well, I’ve finally tracked down a copy of Joshua Greene’s Here Comes the Sun: The Spiritual & Musical Journey of George Harrison (Bantam, 2006) which suggests Alice was in George’s mind too:

“The late Sir Frankie, a multimillionaire lawyer and adviser to England’s Liberal Party, had been “a bit like Lewis Carroll”, George said, “or Walt Disney”. Around the grounds Crisp had dug lakes, planted topiaries, and carved a river that flowed under the property. He had planted thousands of varieties of flowers and trees around the estate and excavated a complex of subterranean caves, some featuring skeletons and distorting mirrors”.

-Joshua Greene, 2006.

So there we have it. Enough at least for loose speculation. Carroll as shorthand for an alternate, perspective-altering universe, with distinctive features:

A place - the surreal and imaginative estate (a bit like Wonderland).

A tone - ambiguously shifting from mystical to humorous and dreamlike.

A set of images - that play with perspective and logic.

A mood - that heightened sense of illusion and poetic crypticism.

In the ‘Crackerbox Palace’ video, directed by Eric Idle of the Pythons, George plays a baby in a pram, being wheeled around by a nursemaid in formal wear, very much like the way Alice encounters tiny doormen, frogs, footmen — servants who are treated seriously despite their absurd scale.

The garden scenes, meanwhile, full of mismatched guests wandering about, are like a Mad Tea Party reimagined in 1970s Oxfordshire.

I’ll let you decide how much in this cocktail of comedy and curiosity is Victoriana, how much pure Python and how much Wonderland.

See you all next time.