08 Interview Special: Andy Maxwell

In which we discuss sound effects, reverse loops, Shepherd Tones and creativity

Each week in Alice & The Eggmen, we explore the weave of connections between Lewis Carroll and the Beatles. Here I interview former Abbey Road sound engineer Andy Maxwell, who now works with Sam Okell on the Beatles remix projects. We talk about the Beatles’ creative process and some of the specific methods that working on the original tapes has clarified.

We spoke for almost 2 hours and got into the wider cultural aspects of Victoriana and child psychology among other topics. But I wanted to keep this tight, so it’s a heavily edited version.

NICK

Tell me - how did you get into this recording lark…?

ANDY

I grew up in Somerset in the early 2000s and got into playing in bands around there. And then, as with anything, you know, you get to a point where you want to record the stuff that you're playing with your mates. And I found I enjoyed the recording process as much as I did being in the band. So I went and studied. Part of the degree was a placement. I got a job at a studio in Angel and my best mate got the placement year at Abbey Road. And then when we graduated, he decided he didn't want to do it anymore, so I started working at Abbey Road. I worked there until 2020 or 2021, when I started working for Sam (Okell).

NICK

So are you working on Beatles remixes with Sam & Giles Martin directly?

ANDY

Joe Wyatt (Giles’ assistant) and I do all the setting up of the tracks, so that Sam and Giles are ready to mix. Whenever we do these kinds of projects, we get all the source material and then re-amp it back into the studio so that we've got natural ambience to use as part of the remix.

NICK

But when did you first get into the Beatles? Let’s talk about that.

ANDY

I guess I heard them first on the radio. My parents weren't fans; they were children of the 80s. My Dad was into prog rock, and my Mum was into post-punk, so I didn't really have much exposure to [The Beatles]. But I remember hearing them for the first time at home, and I remember being knocked over.

NICK

It’s the middle period you came to prefer, though. Why’s that?

ANDY

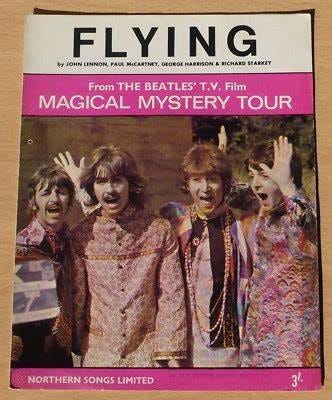

It’s just so wacky and far out. Particularly ‘Strawberry Fields’; I think that's my all-time favourite. It's just everything about it: the way it was done, the sound of it, the way it throws in different influences, the brass and the cellos, and the general psychedelia of it. I'm quite fond of Magical Mystery Tour and the film. I think it's the irreverence of being at the height of their powers, and just going “we're gonna make the most far-out stuff ever” rather than just carrying on making little pop ditties, which they could have done. It's quite brave. It landed. And it sounds great.

NICK

It feels from what I’ve read, that Abbey Road (then EMI Studios) played a big role in all this. What is it about the studio that’s special, as a creative space?

ANDY

I mean, it can facilitate near enough everything. So if you go and say “I want to do this”, the answer is always going to be yes. The only thing I've ever been told ‘no’ to was bringing in a big vat of water. It just feels like sort of a place where you can explore whatever it is you want to creatively, and it will facilitate that. It's not that exciting a space in itself; basically, it's like a massive school hall. I mean, acoustically, it's phenomenal. It sounds great. But you almost have to work to create something magical. It's like a blank canvas in a way, you know…

NICK

So let's take a quick side-step: what do you know about Lewis Carroll?

ANDY

Generally, not that much. It's just one of those things you're exposed to as a child. I’m quite fond of the illustrations and things like that. But I think I only ended up coming to them quite late. But it’s amazing stuff. In terms of just like, being surreal. I think it's just one of those things that the 60s was really suited to because of the psychedelic, out-there, far-out, thing.

NICK

So what connections do you make in your mind?

ANDY

I wonder if a lot of it was trying to revert back to a childlike thing. And play, because I think a lot of our creative process is so much based on play and having fun and - you know - being free.

NICK

Could you expand? How are play and freedom built in?

ANDY

When you listen to songs like ‘Flying’, which I was playing around with yesterday…track 1 has the basic rhythm section. Track 2 I think is a tambourine and then tracks 3 and 4 are literally just playing around with reverse sound effects and stuff like that. And it's just that sort of sense of not really caring.

That's the thing you don't really get as much at Abbey Road today because of how expensive it is. But back then they had the freedom of the whole building so it was just like “no, we're just going to record a whole thing of reverse tape loop effects and see if it sticks”. So I think play’s a big part of their creative recording process.

NICK

How do you link Alice and the idea of play?

ANDY

I suppose Alice is play in another way as well. It's, like, nonsensical and surreal. For a man that's a mathematician, you'd have thought that his idea of things would have been more engineering-based. But maybe that's another parallel - between knowing the rules, and then knowing when to break them and how to break them.

NICK

It's a play between engineering and creativity for sure. Maybe that tension's the heart of it?

ANDY

Interesting. Pushing the boundaries. Trying to see what can be achievable with the technology and also trying to see what can come about by breaking it. Like the Beatles themselves, when they were recording, they were always trying to push the machines. They say ‘the enemy of art is the absence of limitation’, and I think that is certainly true. A lot of their creative process for these sort of wacky sounds was trying to overcome limitations, or acknowledging the limitations and then using them creatively.

NICK

So is it fair to say there's something about creative breakthroughs that involves exploring the limits of something, breaking the rules of what it's been designed for?

ANDY

I guess so. Or taking something that would ordinarily be figured as, a negative feature. And then making that a feature in-and-of itself?

NICK

Can you give me an example?

ANDY

Feedback. Feedback’s something undesirable, but people around then were using it creatively on guitar…

NICK

Which is the song that starts with the feedback?

ANDY

‘I feel fine’.

NICK

The other thing I'm quite interested in, is stuff that's mirrored, like the mirror in Through The Looking-Glass. Things that are backwards, reversed, or louder / softer, close-up / distant — like that way Alice grows and shrinks.

ANDY

It was just twisting things. I guess they got to a point where they wanted to do the opposite of what was done. So if traditionally strings were mic’d up in a really distant way, they'd be like, “oh, let's just do it really close”.

NICK

That's nice. So actually the principle is “do the opposite”.

ANDY

Yeah, “do the opposite”. What's the opposite? Does it sound cool? Can we make it sound cooler? You know you're not meant to overload the desk. Let's do it! Yeah, a bit closer with the drum mic’ing - how that sounds when you hit the compressors harder.

NICK

I also think about the way the Cheshire Cat appears and disappears - it fades! The Beatles loved using fade-ins and fade-outs.

ANDY

The whole ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ recording was like them on the console fading in different tape loops. It became more like a performance.

NICK

What about some other examples?

ANDY

You’ve got ‘Strawberry Fields (Forever)’: there are lots of reverse drums and things like that, that just come in for a little bit and then go out.

NICK

What about sound effects? You must have heard a lot of the additional sounds while working on those original tapes.

ANDY

Well it’s interesting trying to find the original sounds, because they just pulled things from the EMI tape library and then reversed them up and stuff.

‘Magical Mystery Tour’ has got all those kinds of bus sound effects, which again, would have just come from the tape library. I had to find some of those last Summer, when we were doing the remix of ‘Magical Mystery Tour’ for the Blue Album.

But some of them were actually things they recorded themselves. And some of it's just things that they recorded from the radio and brought in at different points. Like that bit in the middle of ‘I Am The Walrus’…1

On ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ they sort of lay down the initial rhythm track, like drums and bass, and there's an organ in there as well. That's got the vocals going through the Leslie as well and the chorus and things like that. But it's like pretty extreme ADT going on there between the sort of bounces to make it sound even more far out.

NICK

It makes me wonder what that does to the listener’s brain? How does it create that psychedelic effect, do you think?

ANDY

I don't really know. It's just like…it's confusing your brain in a way. Your brain is constantly trying to make the two sounds sound the same? You're tricking it, you know. You're gonna always hear ‘oh, but now it's here. And now it's over there.’ You're not letting it settle into one place.

[‘BLUE JAY WAY’ COMES ON…]

ANDY

I remember when we were doing that it'd be the ‘Bernie Box’2 we used which was like a particular ways of achieving phase and things. Some of them were with ADT. This one was a bit more of an extreme sounding ADT. They used that on ‘Across the Universe’.

NICK

Is ‘Across the Universe’ another trippy one in your book?

[‘ACROSS THE UNIVERSE’ PLAYING…]

ANDY

The reverse effects are just coming in and out. They weren't on the original four track, they just fly things in on the mixing stage. They'd be like ‘oh, we want to throw this in’. Sometimes ad libs and stuff like that as well. Remember, like Get Back ‘Queen says no to pot-smoking FBI members’ or something like that. That wasn't in the actual four track.

NICK

What about the soundstage. There's something weird about it – it feels quite 3D.

ANDY

Yeah, hear this cello, that kind of short tape delay thing. Where you've like delayed the second head so it records it with feedback as well. So that's not, like, baked-in. You're playing around with the brain's perception of it, I suppose.

NICK

It's disorientating?

ANDY

Yeah. Intentionally, so. Yeah. And speed changes are just like a big part of their soundscape. It just something interesting on the voice as well, particularly the formants - the sort of vowel sound if you slow things down. The vowels become more elongated.

NICK

A bit like ‘Rain’…

ANDY

…when they record the rhythm section at like a faster speed, right, and then slow it down to make it more drowsy-sounding.

[‘RAIN’ COMES ON…]

This sounds like a vocal that would have been recorded at faster speed and then pulled down and there’s something interesting it does to the vowel sound. Oasis made a whole career out of this song really.

NICK

I think it just makes you feel like all these different worlds are colliding.

ANDY

I'd say so. Yes, it's putting you in a different space. Like you know, just bringing in a lot of birds in a certain place or bringing in the bus sounds making you feel you're in a certain space. It's trying to take you away from just being there with your stereo hi-fi or your Sonos or whatever you're listening to it on, and sticking you in this world that they're trying to create.

NICK

I feel like we should listen to ‘Strawberry Fields’ then

ANDY

Two takes, isn't it? It's the one they recorded at two different speeds. They wanted to bring them together…

[‘STRAWBERRY FIELDS FOREVER’ STARTS UP…]

NICK

The Mellotron is interesting because it's pretending to be a flute or whatever, isn't it? So it's kind of an early synth. But it’s just made of tapes, isn't it?

ANDY

Mellotron on the flute setting? It's taking what you're expecting, and trying to play with it […and] that could also be something like a tack piano? It's either like tack piano or harpsichord. And reverse drums, it just keeps going down and down and down.

Isn't that a bit ‘down the rabbit hole’?

NICK

In what sense?

ANDY

Sort of like dragging and pulling away and like, I don't know, the sense of foreboding - it's like a big sense of calling in this song I find personally.

NICK

Can you describe what makes you feel that way?

ANDY

Yeah, this ‘let me take you down’… so it starts quite simple and approachable and then becomes much more frightening in a way. It’s that feeling of falling as well. That sort of tripletty kind of feel. It's like it keeps in a four and then goes into three when it goes ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’, like this polyrhythmic thing.

NICK

Playing with your sense of time. And again, tricking your expectations.

[ONTO ‘LUCY IN THE SKY…’]

There's something interesting with the DS0-1 because it's like an organ, isn't it, when you blend different stops together and so the actual sound is quite an unusual blend.

ANDY

It's quite far-out, that sounds like a really quick wobble as well.

NICK

His voice is transformed too, isn't it?

ANDY

It’s a short slap-back tape delay and then probably in the chamber it’s got a rotary Leslie cabinet thing on it […] the descending bassline as well…is a feeling of constantly going down and then back up.

NICK

‘I Am The Walrus’ also has that thing at the end. It's like an aural illusion. Like it keeps going up. I mean, it's not possible to keep going up. You know that bit?

ANDY

Shepherd Tones!

NICK

Tell me about Shepherd Tones.

ANDY

It’s when it feels like it's constantly rising. Because when you get to the end of the pitch it just starts again from the bottom and overlaps and just feels like it's a never-ending rising tone.

NICK

That's so Alice, because it's quite mathematical. It's a trick that's created by some kind of physical thing that you could codify, but it does something to the brain that creates illusions. Auditory illusions. Just like Escher’s optical illusion.

[‘I am The Walrus’ playing]

ANDY

It just sounds so gnarly, so angry and in-your-face and up-close distorted and that's one thing that sticks out on this one. Also the naughtiness and things, playground chants and stuff.

When they were recording it, they wanted to make more room for wacky sounds. So they just took the whole mix and then combined it down to one track so that they had three other tracks. Wacky stuff on wacky stuff. That sounds amazing. Just little things that pop in and keep your interest, like ‘here's a little bit of cool cello’, ‘here's a little bit of Mike Sammes singers saying some nonsense’…

NICK

And you really wouldn't know it was them; I'm sure if you've heard their actual (master) tapes you must hear them actually singing it but the way it's been processed…

ANDY

…yeah, it doesn't sound like a voice because of how it sits in the mix. Then you've got the strings doing it as well as the singers. Then layering…

NICK

So if you had to sum up now, what’s your take?

ANDY

I guess manipulating perceptions and twisting them. Something about playing around, and that being fun and free. Just trying to, you know, think about what you’re expecting and twisting it. Trying to trick your brain into giving you something that you weren't expecting.

Having been suppressed for so long, coming into a time when there's a lot of freedom and the world feels like quite an optimistic place. And if you're talking about Abbey Road, it's like the use of the studio as an instrument. They were probably the first kind of like, culturally significant musical act to be doing that.

NICK

And the idea of a child protagonist. Navigating the adult world.

ANDY

I can see that. Totally. ‘You can't do this’. ‘You're not allowed to distort this’. ‘You're not allowed up here in this room’. This room is for adults, then winding up there eventually and then making something special. Getting away with that.

NICK

Andy, thanks so much.

2024

“These were taken from a BBC Radio broadcast of William Shakespeare’s King Lear, which Lennon heard while listening to the radio at Abbey Road. He managed to convince George Martin to combine fragments of the broadcast with the studio mix, meaning that disjointed pieces of the play’s dialogue found their way into ‘I Am The Walrus’. Most of that dialogue is taken from Act Four, Scene 6, when Oswald, dying, delivers the line, “Slave, thou hast slain me. Villain, take my purse.” “I know thee well: a serviceable villain,” says Edgar, looking down at Oswald’s body. “As duteous to the vices of thy mistress As badness would desire.” - The literary references in The Beatles 'I Am The Walrus'

I’ll try to find a picture of the mythical Bernie Box but it’s hard to locate. For anyone interested in the studio equipment, I cannot recommend this book highly enough: RTB Recording The Beatles The Studio Equipment & Techniques Book Kehew and Ryan | Limited Edition Book

another fab post ... reminded in part of Ian Leslie's March 8 Substack post about "The Potency of Jokes - Why Breakthroughs Emerge From Fooling Around" https://www.ian-leslie.com/p/the-potency-of-jokes