09 Pop goes the Pepper

Elvis' gold limo meets prime Victoriana: dream narrative & the counterculture.

It’s June 1st 1967. Pop becomes art as the Beatles silence the doubters.

Every week on Alice & The Eggmen we explore the curious connections between Lewis Carroll and The Beatles. Sometimes the connections are subtle, sometimes almost invisible.

That’s not the case with this week’s subject: 1967’s Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

We’ll be talking about specific songs (‘Lucy…’, ‘Mr Kite’, ‘A Day In The Life’…).

We’ll be talking about studio experiments, and sonic Wonderland.

We’ll be talking about pop-art, Jann Haworth and Peter Blake.

We’ll be celebrating accidents - the gift of error in language and sound.

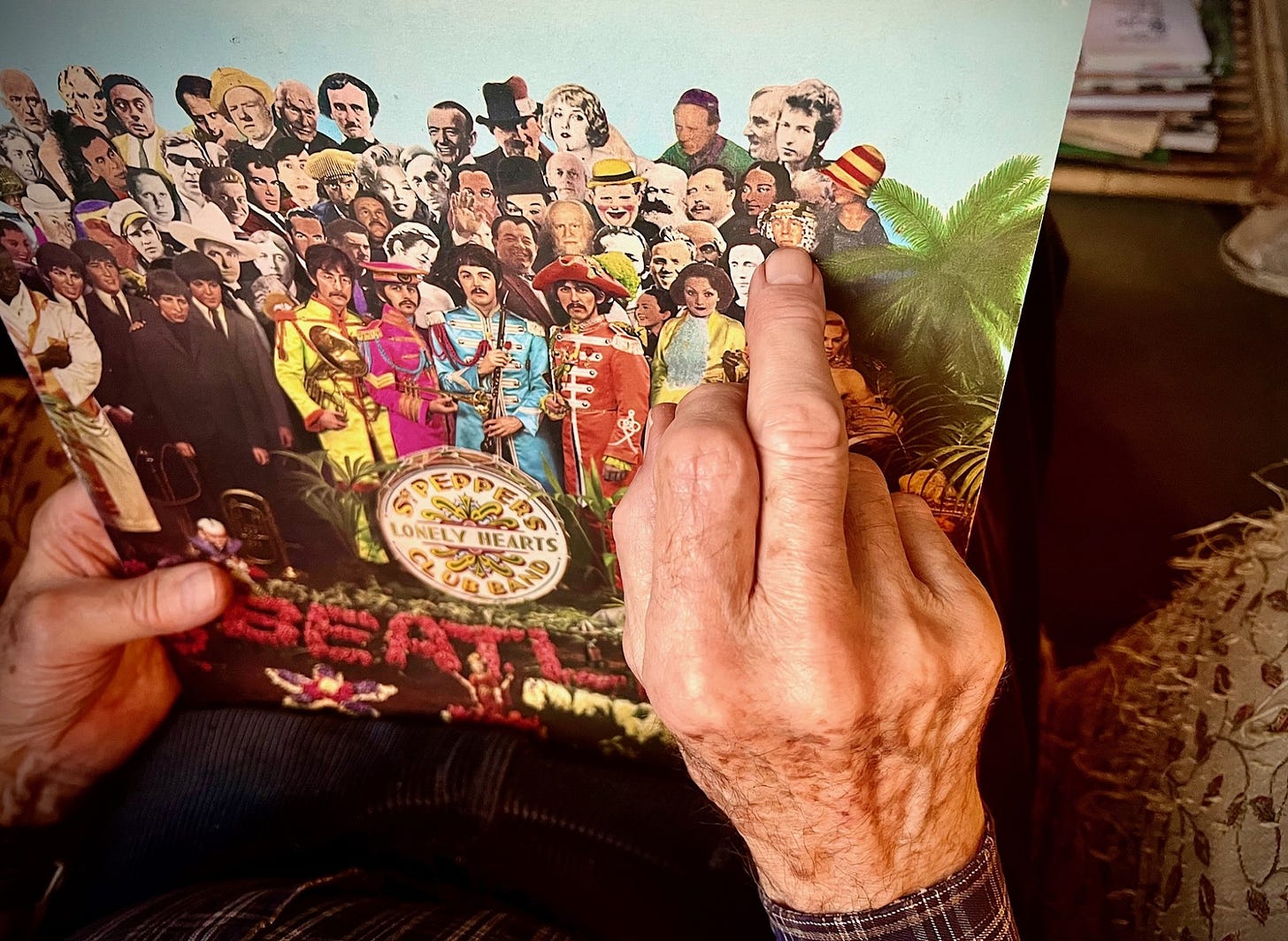

This one’s quite personal, for me. Pepper is an important part of my childhood: it’s how I got into pop. Yes, my Mum owned a few records by Françoise Hardy. But music at home was mainly a Teutonic diet of my Dad’s tastes: Wagner, Beethoven, Handel, and for light relief… Gilbert & Sullivan, or a recording of train sounds. But, as I discovered by chance, rifling through the vinyl cabinet, and nestled near some 78rpms, he also owned 3 Beatles albums: A Hard Day’s Night, Help and Sgt Pepper.

Pepper was wildly colourful, playful (the cut-out moustaches) and disconcerting. I could follow the lyrics as they were (unusually) printed on the back in full, perhaps cementing the statement of this album as art. I marvelled at the gatefold format, with its mysterious inner world. And I was totally enthralled and thrown in equal measure by the voices - I couldn’t make out who was who. And so it began.

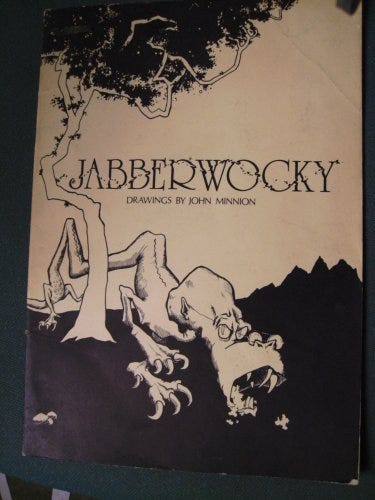

In parallel Carroll was entering my brain, especially this wondrous 70s edition of Jabberwocky illustrated by John Minnion, with Mome Raths and Borogoves cast as groovers and stoners.

So the coming together of both worlds is pleasing to me, and I want briefly to list the 7 ways in which Carroll & Pepper intersect.

#1 Lewis Carroll - he’s only on the bleeding cover!

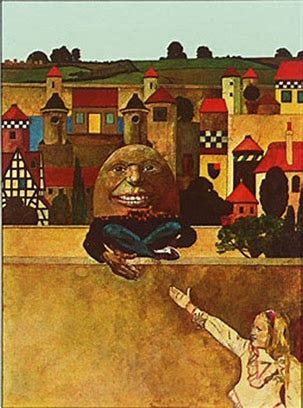

Here’s my Dad, now 89, with his copy of Sgt Pepper. As I think most people know, the cast of characters behind The Beatles were historical figures and heroes, chosen by the Beatles. And Lewis Carroll was one of them. Dad’s actually pointing to Peter O’Toole here, but Carroll is the pale figure just to the left of his finger.

In case you missed it, here he is again.

While it looks like a collage, the composite effect was actually created by making life-sized cardboard cutouts of each person and assembling them in rows behind the Beatles, plus waxwork figures from Madame Tussauds, including the younger moptops themselves, Sonny Liston and Diana Dorrs.

#2 It’s a ‘concept’…

Carroll’s on the cover. But of course that’s just his pen name. Charles Lutwidge Dogson (Lutwidge = Lewis, Charles = Carroll in Latin) is the person depicted. And he was a lover of puzzles, conceits and concepts, from Alice in Wonderland being a game of cards to Through The Looking-Glass manifesting a chess game.

Pepper was the first album the Beatles made after the straight-jacket of touring had been removed. Often dubbed the first ‘concept album’, it’s not really a coherent narrative, in the manner of The Wall. But it does contain conceptual elements…

First and foremost, Pepper would be a vehicle. Literally inspired by a vehicle - Elvis’ gold limo:

We came back, and we started to think, ‘What can we do? We don’t want to tour again […] We heard that Elvis Presley had sent his gold-plated Cadillac out on tour. He didn’t go with it – he just sent it out. And people would flock to see Elvis’ Cadillac, and then it would go to the next town and those people would flock.

So we thought, ‘That is brilliant! Only Elvis could have thought of that […] what we should do is, we should make a killer record, and that can do the touring for us.

- Paul McCartney

And if the album itself would do all the talking, then why not also create a fictitious band and a fake concert to house the sequence of songs.

Too much probably has been made of this aspect. After all, it doesn’t really follow through fully. As a concept it’s only half-born, but as piece of imaginative experimentation it’s a real breakthrough - an album to be listened to, not danced to. Listen to George Martin and part of the concept really is an experiment in imagination, that starts with the title song.

“We were trying to create the illusion of being able to shut one’s eyes and see a complete picture”

- George Martin

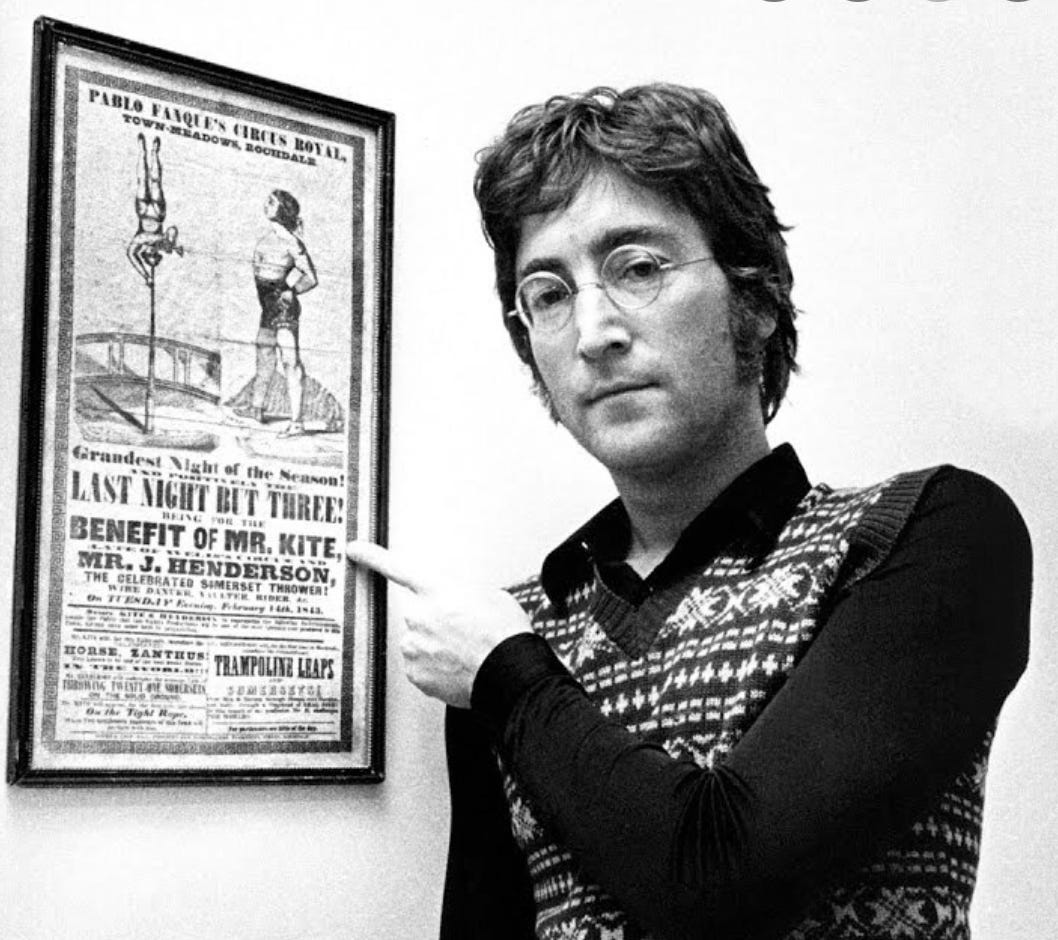

We’ve already talked about the Carrollian nature of these calls to imagination, it’s just that here the Beatles were doing it sonically as well as lyrically. “Picture yourself on a boat on a river” does it. And John told Martin that for Mr Kite he wanted to “smell the sawdust”.

#3 It’s in the name

Carroll’s a freak for puns and portmanteaus. Linguistic invention and gameplay.

Part of The Beatles creative process, as we saw last time, was to embrace mistakes, to see them as happy accidents. Later, Brian Eno’s Oblique Strategies cards would contain one reading “honour your error as a hidden intention”. It’s the same here. Relishing what I call the “gift of error” is part and parcel of their writing and recording process. It’s often claimed that Lennon, and Carroll, were both dyslexic (something I need to dig into a little more - bear with me) and that this opened their minds to punning and word play.

In a similar way, Paul loved simply riffing on language and so the name Sgt Pepper, on a flight back from the US with Mal Evans, was born:

We were having our meal and they had those little packets marked ‘S’ and ‘P’. Mal said, ‘What’s that mean? Oh, salt and pepper.’ We had a joke about that. So I said, ‘Sergeant Pepper,’ just to vary it, ‘Sergeant Pepper, salt and pepper,’ an aural pun, not mishearing him but just playing with the words.

Paul McCartney,

I won’t make the claim that ch.6 of Alice in Wonderland, pig and pepper, played a role here, even subconsciously, but it’s certainly a happy coincidence. In an interview about “Mr Bellamy” from Memory Almost Full (itself a piece of found language, from his phone), Paul explains that in his process he often starts with a fragment or a line and then demands of the fragment “explain yourself!” - and everything flows from there.

Once the idea of a fictitious Sergeant appeared, the rest followed, by semi-logical extension… a military uniform, a band leader, a memory of his Dad’s band with the drum at the front…

It’s fragments of memory and allusion coming together in a way that parallels the creation of the first two recordings for the album, ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ and ‘Penny Lane’.

#4 It’s a big dollop of Victoriana

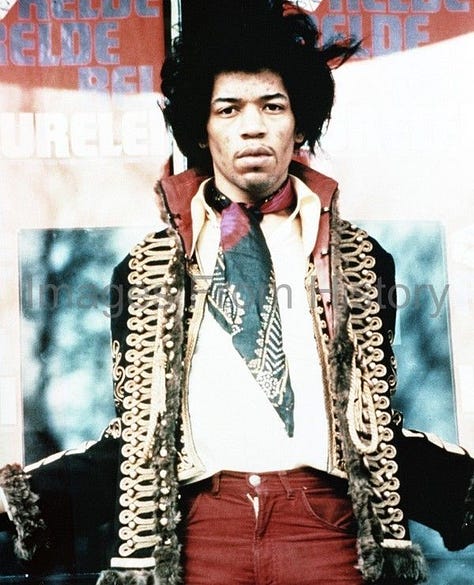

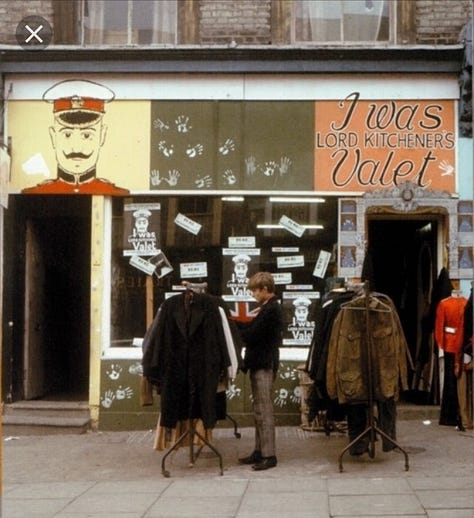

Post-war modernism, the reconstruction of England, with new high-rises, sparked a new interest in what had gone before, a rediscovery of artists like Aubrey Beardsley - whose 1966 V&A show1 was the talk of London, and inspired the cover of Revolver. Victoriana was all the rage, creating a broader sense of nostalgia for Lewis Carroll’s world, that showed up in things like fashion. Among the many boutiques in swinging London - including one called ‘To Jump Like Alice - was “I Was Lord Kitchener’s Valet”, which specialised in military-style garments, as sported by Hendrix, Jagger and more:

While the Pepper uniforms were crafted by M. Berman Ltd, the style is drawn from the same well, with a psychedelic twist. And of course, the heady whiff of Victoriana continues in Being For the Benefit Of Mr Kite, where a Victorian circus poster — bought by John in an antiques shop — provides 90% of the lyrics, and all of the sonic inspiration, with its swirling, cut-up, calliopes.

#5 It’s in the themes

Alice is unusual in literature for being a child hero(ine). Long before Harry Potter and the like, Carroll’s protagonist stands for the power of childlike imagination in a world of adult mediocrity and stultifying order.

60s counterculture was nothing if not a simultaneous rejection of adult values — staged in Abbey Road as a rebellion against grown-ups, rules, white labcoats and ties — and the embrace of youth, youth culture, youthful energy. Footage of 60s London is full of stiff people in bowler hats looking askance at young people in miniskirts and boots, who are clearly enjoying their new-found freedom.

And so, in a number of places, we find stories about the tussle between authority and originality, control and freedom. Take the first verse of ‘Getting Better’:

I used to get mad at my school (Now I can't complain)

The teachers who taught me weren't cool (Now I can't complain)

Holding me down

Turning me 'round

Filling me up with your rules- ‘Getting Better’ (1967)

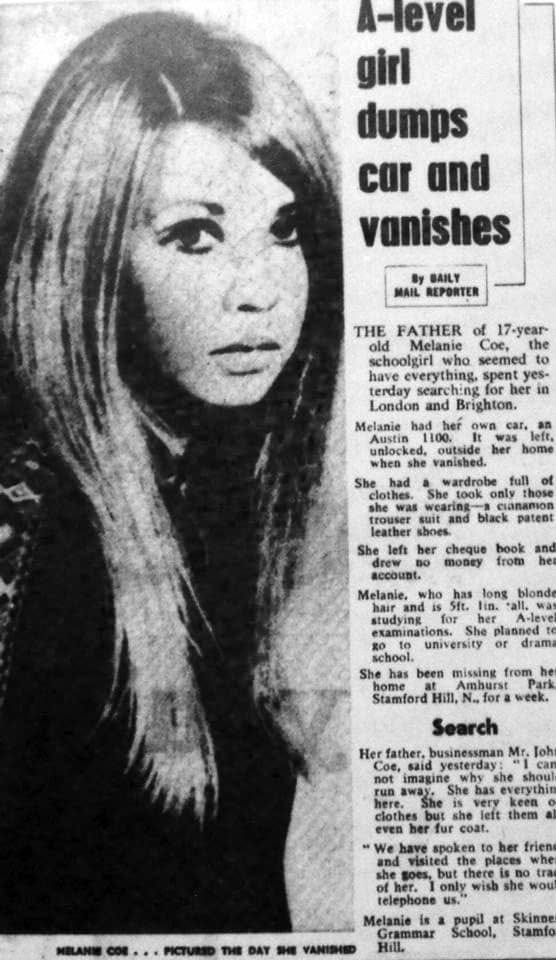

And then we have ‘She’s Leaving Home’. It’s a song based on a true story, set in East London’s Stamford Hill — in my neighbourhood — about 17-year old Melanie Coe, that Paul read about in the newspaper. Bizarrely Paul had already met her on Ready Steady Go! in 1963 (see the picture on the right), but was unaware of the coincidence.2

Paul & John play narrator and parents, dramatising the generational divide:

Quietly turning the backdoor key

Stepping outside, she is freeShe,... (we gave her most of our lives)

Is leaving (sacrified most of our lives)

Home (we gave her everything money could buy)- ‘She’s Leaving Home’ (1967)

On the surface, a simple, albeit heartrending, tale of youthful adventure, the song’s production continues the dreamlike tone of the whole record, with the opening harp arpeggios processed with subtle delay to create a shimmering, varisped, aural tapestry.

#6 It’s in the dreaming

And dream narrative is ubiquitous.

Just like Wonderland, scenes bleed into one another, with transitions (or cross-fades) playing a central role in production, from the opener into ‘With A Little Help From My Friends’ and from the reprise into ‘A Day In The Life’.

And then there are the dream references. As the album’s final song shifts gears from John’s section, into the orchestral climb, an alarm clock yanks us out of woozy half-sleep into wakefulness, and then in a cloud of smoke, “I went into a dream”, and back into the next section. It’s a strange cocktail of 1st person narrative “I read the news today…”, 3rd person “somebody spoke”, “ellipsis “woke up, got out of bed…” and reported speech “now they know how many holes it takes”.

Lucy is also Alice, the ‘dreamchild’, beckoning and guiding the listener from vignette to vignette, images — newspaper taxis, cellophane flowers, looking-glass ties —appearing mysteriously, as the song drifts along its metaphorical river, water imagery a symbol metaphor for the subconscious, as well as a direct allusion to the riverbank that starts Alice’s adventures.

It’s a song of yearning:

There was also the image of the female who would someday come save me — a ‘girl with kaleidoscope eyes’ who would come out of the sky,” he said. “It turned out to be Yoko, though I hadn’t met Yoko yet. So maybe it should be ‘Yoko in the Sky with Diamonds.'

John Lennon

#7 epilogue - Alice goes on

The cover design and shoot were masterminded by wife & husband artists Jann Haworth and Peter Blake. I’m taking pains not to put Blake first since that’s been what typically happens - Haworth deserves an equal share in the legacy of Pepper.3

I don’t need to say more about it here; what’s important is the involvement of both in the ongoing Carroll story, because — to me — it just goes to show how central Alice was to the ‘imaginarium’ of post-War Britain. While Californian counterculture assimilates Alice via Headshop culture, Ken Kesey, and more, Alice’s English afterlife leans more on the pastoral tradition. I’d argue this is also huge in the Beatles’ work, in the omnipresence of flora and fauna and landscapes (“sitting in an English garden”…).

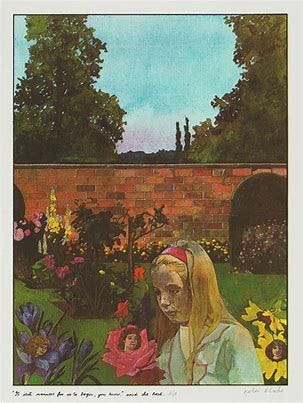

The couple co-founded a collective called ‘The Brotherhood of Ruralists’, who formed in 1975 in Somerset. Blake produced one of the most stunning illustrations of the Alice Books, which are both more pastoral, yet just as defamiliarising as any.

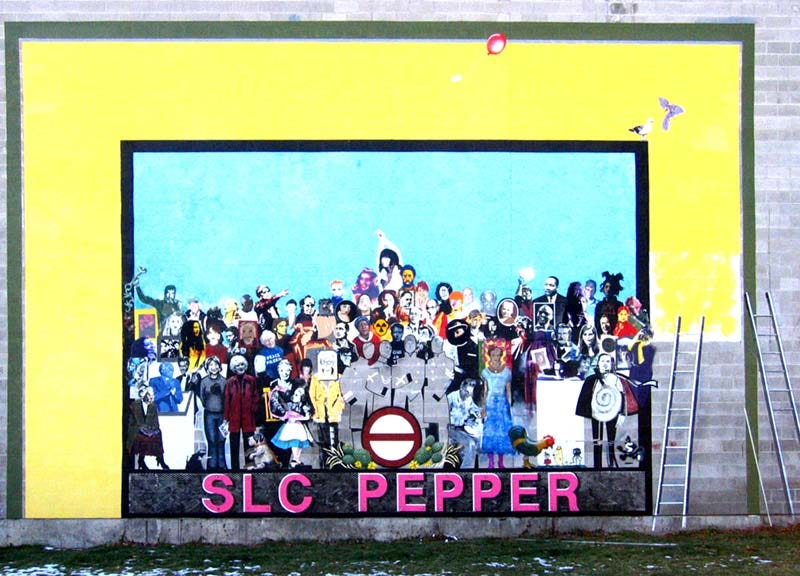

In 1979, Haworth, founded and ran ‘The Looking Glass School’ near Bath, that focuses on arts-and-crafts. Later in life she’s returned to Pepper, creating a giant public mural called SLC Pepper, in which the original faces are replaced with an updated pantheon of modern artists, creatives, activists…

Here’s what Jann has to say:

"The original album cover, famous though it is, is an icon ready for the iconoclast. We will be turning the original inside out... ethnic and gender balancing, and evaluating for contemporary relevance."

- Jann Haworth4

Nice to see iconoclasm continuing its path. Next time I’m going to try to do justice to ‘Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds’, John & Paul’s attempt to “do a Lewis Carroll” inspired also by a drawing by Julian (‘Jude’) Lennon.

See you there.

Rolling Stone, 2017, Meet the Runaway Who Inspired Beatles' 'She's Leaving Home'

SLC Pepper page, on Jann Haworth’s site.

Incredibly fun, interesting, and enlightening analysis! Something about you starting making discoveries in your parents albums feels like Alice too - through the gatefold if you will.

oh wait, so there really ARE lots connections between the Beatles and Alice in Wonderland ... love the personal connection to St Peppers and your dad