Last week we took a deep dive into the album covers, tracing the Carroll clues from distortion and scale-play (with Rubber Soul & Revolver) to the more explicit (Carroll’s image on Sgt Pepper, Walrus imagery on Magical Mystery Tour etc). I even made a play for The White Album as a kind of blank looking-glass (or creative portal).

This week will be shorter, simpler, and less rambling, I hope. I just want to sum up 3 brief elements:

Harrison’s Wonderwall Music (1968)

Lennon’s 70s sonic dreamworlds (Plastic Ono Band, Mind Games, Imagine, ‘#9 dream’)

And McCartney’s continued fascination with Magritte (and all that brings)

Let’s start in 1968…

Wonderwall Music is — I think — officially the first solo album by a Beatle (pipping John & Yoko’s Two Virgins to the post by a whole 10 days!), and the first release from the newly-minted Apple label. We’ve already covered Wonderwall (from the Fool’s armoire to Oasis) in a previous post (one of my favourites), but it’s worth revisiting the cover specifically.

The artwork is a commission by Apple from American artist Bob Gill and was painted in the style of Magritte (an important figure for ‘60s Beatles and McCartney till this day). It captures the sense of divide — between normality and the exotic, traditional norms and youth culture, repression and desire — that are foregrounded in ‘60s counter-culture and dramatised in Wonderwall through the adjacent apartments of Professor Collins and model Penny Lane (played by Jane Birkin).

The missing brick was apparently a bone of contention, insisted upon by Derek Taylor because — as in the film — it needed to show that the old guard “had a chance”. Peep hole, portal, rabbit-hole… Wonderwall and Wonderland are riffs on the same theme of transportation, fantasy, and imagination.

And of course, it’s not just the title that inspired Noel Gallagher, the ‘Wonderwall’ cover, shot on Primrose Hill, also tips its bowler-hat to Magritte:

Let’s have some Primal Scream…

1970 was a year of multitudes for John. His ‘divorce’ from the Beatles felt like liberation, but was embroiled in conflict (and law suits). He was trying for a baby with Yoko, but she’d had 2 miscarriages. He left the UK to spend more time in America, where he encountered Arthur Janov. Inventor of ‘Primal Scream’ therapy, his book was published in 1970, shortly before Lennon had started work on what would be his first solo release.

“[They] mailed the book without any letter explaining why they were sent […] John got his copy about two weeks ahead of publication, he read it, and he came to me. Listen to his new album if you want to know what he got out of it.”

-Arthur Janov, Rolling Stone.

Forced by visa restrictions to return to the UK, John organised a reunion with estranged father Alf, who was back on the scene. To say that this meeting at Tittenhurst Park was less than harmonious would be the understatement of the Century, as John launched into primal scream-inspired tirade after tirade:

“There was no doubt whatsoever in my mind, that he meant every word he spoke, his countenance was frightful to behold, as he explained in detail, how I would be carried out to sea and dumped, ‘twenty – fifty – or perhaps you would prefer a hundred fathoms deep.’ The whole loathsome tirade was uttered with malignant glee, as though he were actually participating in the terrible deed”

Alf Lennon1

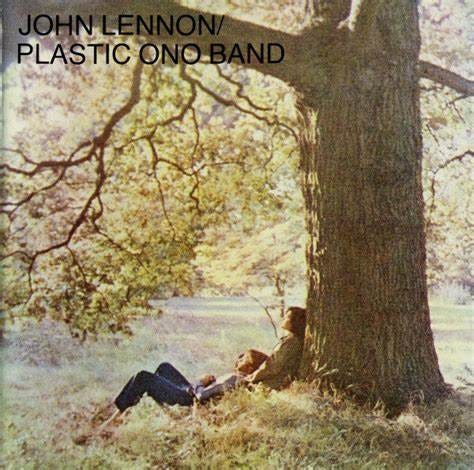

The resulting Plastic Ono Band feels like total rupture. Confessional and raw, from the ominous death-knell sounds of opener ‘Mother’ to the litany of rejections in ‘God’ — “I don’t believe in… [Hitler/Beatles/Mantra etc]” the album marks the end of something — “the dream is over” — and the beginning of acceptance: “I was the Walrus and now I’m John”.

That means the end of the overt psychedelic and playful Carrollian period and the birth of a more grounding, organic, phase. In place of everything John was trying to be, the many masks, games and fantasies, now…

I just believe in me

Yoko and me

And that's reality-John Lennon, ‘God’, Plastic Ono Band (1970)

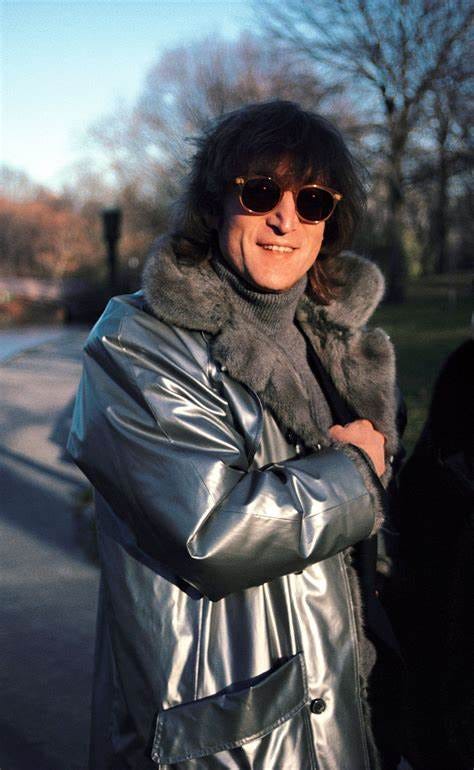

Symbolising the simplicity of this ‘just Yoko and me’ idea, the cover art is perfect and peaceful, a stark contrast with the pain and anger of many of the songs it contains, an emotional full stop echoing its final words.

The cover photo was shot in Tittenhurst Park, a place of relative peace and happiness for the couple. I can’t help but see an emotional through-line, harking back to Strawberry Fields, the place, and its “symbolic” invitation to represent “anywhere you want to go”. Not to mention the line “no-one I think is in my tree”.

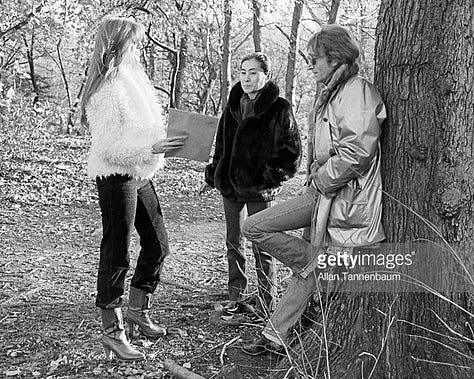

This central symbol of the tree fascinates me. So many of the images of Lennon in New York are surrounded by Central Park trees.

OK, you can say I’m cherry-picking. Where are the shots walking down the sun-kissed pavements of Manhattan? And yet, there’s clearly something about them that speaks to — and speaks of — his childhood, his safe spaces, like Strawberry Fields.

Here are some more from the Tittenhurst Park photoshoot:

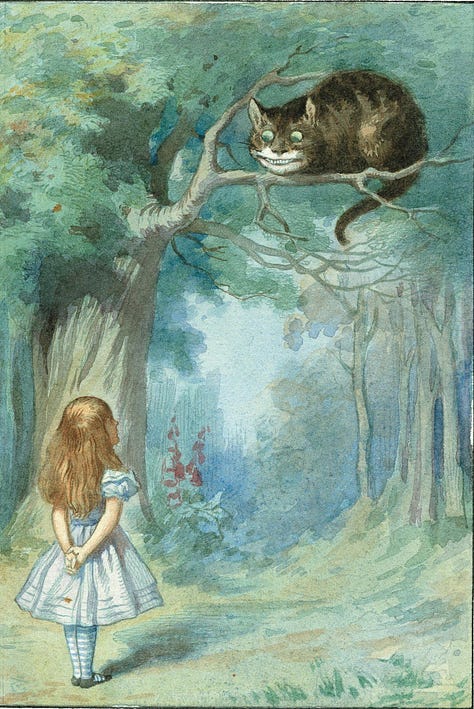

But of course — if you’ll humour me — curling up at the base of a tree is also a feature of John’s favourite childhood books.

At this, the whole pack rose up in the air and came flying down upon her; she gave a little scream, half of fright and half of anger, and tried to beat them off, and found herself lying on the bank, with her head in the lap of her sister, who was gently brushing away some dead leaves that had fluttered down from the trees upon her face.

"Wake up, Alice dear!" said her sister. "Why, what a long sleep you've had!"

"Oh, I've had such a curious dream!" said Alice. And she told her sister, as well as she could remember them, all these strange adventures of hers that you have just been reading about. Alice got up and ran off, thinking while she ran, as well she might, what a wonderful dream it had been.

-Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865)

There’s clearly something elemental about these kinds of English oaks that goes beyond Alice alone — including the fact that John & Yoko planted acorns to symbolise their union — but equally they’re iconic images from versions of Alice John would have had etched in his mental sensorium.

I scarcely dare point out that the tree is also iconic in the video for ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’, albeit a strange and rather bare / isolated specimen.

Imagine…

The fact that creative work has the power to transport, to reframe and stimulate was a source of fascination to John & Paul, from an early age. And that tools as simple as language and harmony had this power doubly so.

Now Paul tends to underplay the radical message of ‘Imagine’ (John says it’s “anti” lots of things) and we also need to acknowledge the debt to Yoko’s Grapefruit which contains multiple instructions to ‘imagine’ as well as the quote from the back cover: “Imagine the clouds dripping. Dig a hole in your garden to put them in.”

And yet it’s also true how for both John & Paul, the invitation to imagine, is a Carrollian move, that first surfaces in ‘I’ll Get You’ (1963), “Imagine I’m in love with you…”).

The word and idea of ‘imagine’ is something John would repurpose in his own song ‘Imagine’. It’s also a bit like the opening of ‘Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds’, with its exhortation to ‘Picture yourself…’ So it’s a filmic thing, as well as a literary thing. When I say ‘literary’, I think of the imagined world of Lewis Carroll that John and I both loved so much. Carroll was a big influence on both of us; that can really be seen in John’s books In His Own Write and A Spaniard In The Works.

Paul McCartney, The Lyrics: 1956 To The Present

The Imagine (1971) cover overlays polaroids of John by Yoko, with cloud paintings.

As Lennon explains:

My album front and back is taken by Yoko as a Polaroid. It’s a new one called a Polaroid close-up. It’s fantastic. She took a photo of me, and then we had this painting off a guy called Geoff Hendricks who only paints sky. And I was standing in front of it, in the hotel room and she superimposed the picture of it on me after, so I was in the cloud with my head. And then I lay down on the window sill to get a lying down picture for the back side, which she wanted with the cloud above my head. And I’m sort of ‘imagining’.

-John Lennon

Now it’s pretty commonplace to see clouds as a representation of “ideas” today, so I think it’s worth just remembering how specific these images are in Lennon’s work:

"Climb in the back with your head in the clouds / And you're gone” - ‘Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds’

“The clouds will be a daisy chain / So let me see you smile again” - ‘Dear Prudence’

“Julia, sleeping sand / Silent cloud, touch me / So I sing a song of love, Julia” - ‘Julia’

Imagination and dreaming by this time have shifted from personal adventure, to political imperative, a radical act. Easily dismissed as naive, perhaps, nonetheless John sees the radical act of imagination as “faith in the future”:

So keep on playin' those mind games together

Faith in the future, out of the now

You just can't beat on those mind guerrillas

Absolute elsewhere in the stones of your mind

Yeah, we're playin' those mind games forever

Projectin' our images in space and in timeJohn Lennon, ‘Mind Games, from Mind Games (1972)

Am I reading too much into it, or does the dream narrative contained in ‘I’m only dreaming, ‘A Day in the Life’ and others not continue in the cover of Mind Games (which as we’ve seen is less the manipulative meaning of mind games, and more earnest play-through-dream)?

Number 9

A favourite number of John’s, the number 9 is perhaps best known for its repetitive announcement “number 9, number 9, number 9…” in ‘Revolution 9’ on the White Album", but ‘#9 Dream’, from 1974’s Walls & Bridges, came to Lennon in a dream.

Lennon has said that the song was just "churned out" with "no inspiration".[2]

That's what I call craftsmanship writing, meaning, you know, I just churned that out. I'm not putting it down, it's just what it is, but I just sat down and wrote it, you know, with no real inspiration, based on a dream I'd had.

— John Lennon, 1980[2]

Classic dismissive John from this period. Yet May Pang remembers it differently:

"This was one of John's favorite songs, because it literally came to him in a dream. He woke up and wrote down those words along with the melody. He had no idea what it meant, but he thought it sounded beautiful."[2]

-May Pang

Take a close look at the lyrics, shown here on the inside spread, and we see the trace of Carroll still present:

On a river of sound

Through the mirror go round, round-John Lennon, ‘#9 dream’, Walls & Bridges (1974)

These Carrollian images — a “river” of sound, “through the mirror” link up with dreamy, protective trees in the visual lexicon of 70s John.

Magritte’s glasses

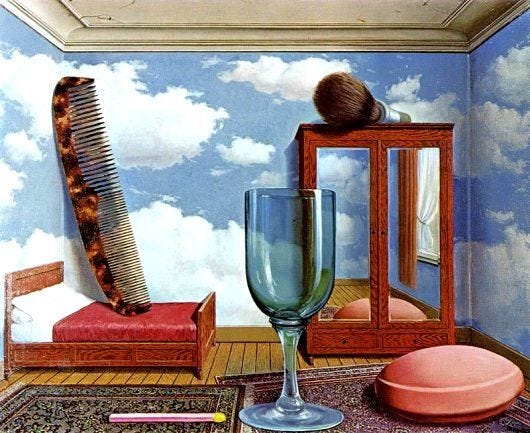

Paul was given a pair of Magritte’s glasses as a birthday present from Linda. He keeps them on his desk. And they remain a symbol of how seeing through surrealist glasses overlays layers of imagery onto often surreal lyrics and music in solo Paul.

As Paul himself explains:

“Linda bought me these for my birthday once,” McCartney said of the gift from his late wife. “Georgette, [Magritte’s] wife, was selling the contents of his studio and Linda bought me the easel and his spectacles and some small linen canvases which I didn’t dare paint on. I’m such a huge fan that was just mega. I was intimidated for weeks about painting on the canvases but in the end I just went, ‘Agghhhh!’ and I did. Then I tried on the glasses which are a very powerful prescription; they’ll give you a headache! What I love about Magritte is he turned the world upside down and inside out in terms of meaning and significance. Science and philosophy and religion are starting to converge on this idea that, whatever hat you put on, you are still you ... Magritte’s specs are a reminder: the world is a jungle of crazy interpretations.”

-Paul McCartney2

We’ve already shown how Magritte was influenced by Carroll and how Magritte influenced the Apple image. And we’ve already wondered whether the rose image from Red Rose Speedway isn’t a subtle allusion to Magritte, whom Paul clearly had in the back of his mind throughout his career, from the mid 60s on:

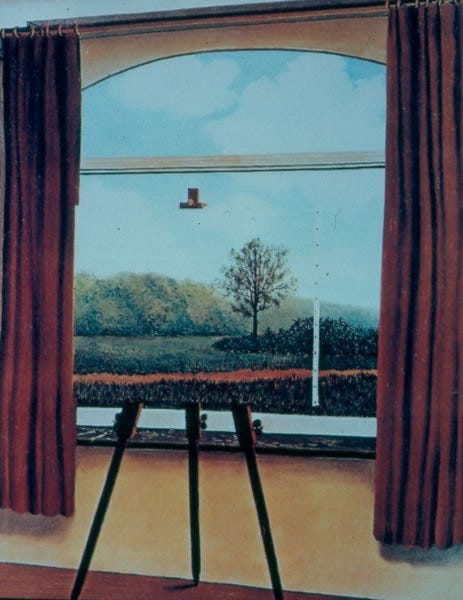

And just for the record — at the risk of repeating myself — the cover art for ‘Mull of Kintyre’ is a clear homage to Magritte’s series of easels:

So I was both amused and not surprised to stumble upon this concert poster from Oakland in 2002:

It doesn’t take a genius to recognise the reference work here:

Yet again, the presence of reality-distorting clouds, mirrors and overgrown objects in rooms echoes so many of the Alice themes that I’m going to go ahead and claim it. And leave it there for this week.

See you next time for — I think — The White Album.

Nick.