Every week on Alice & the Eggmen, we trace the sometimes overt, and sometimes subtle weave, of Lewis Carroll influences on the Beatles’ world and work. This week it’s the turn of the so-called White Album. And I have a new Alice discovery to share.

So let’s dive in.

After a run of quasi-concept albums (Sgt Pepper, Magical Mystery Tour), this is a concept that’s an anti-concept. The unity is diversity: a compendium of genres from proto heavy-metal to lullaby to pastoral to musical hall. The album is a musical flowering, and a withering at the same time. It’s the ‘widest’ spectrum of any Beatles record, and also where the seams pull apart the most.

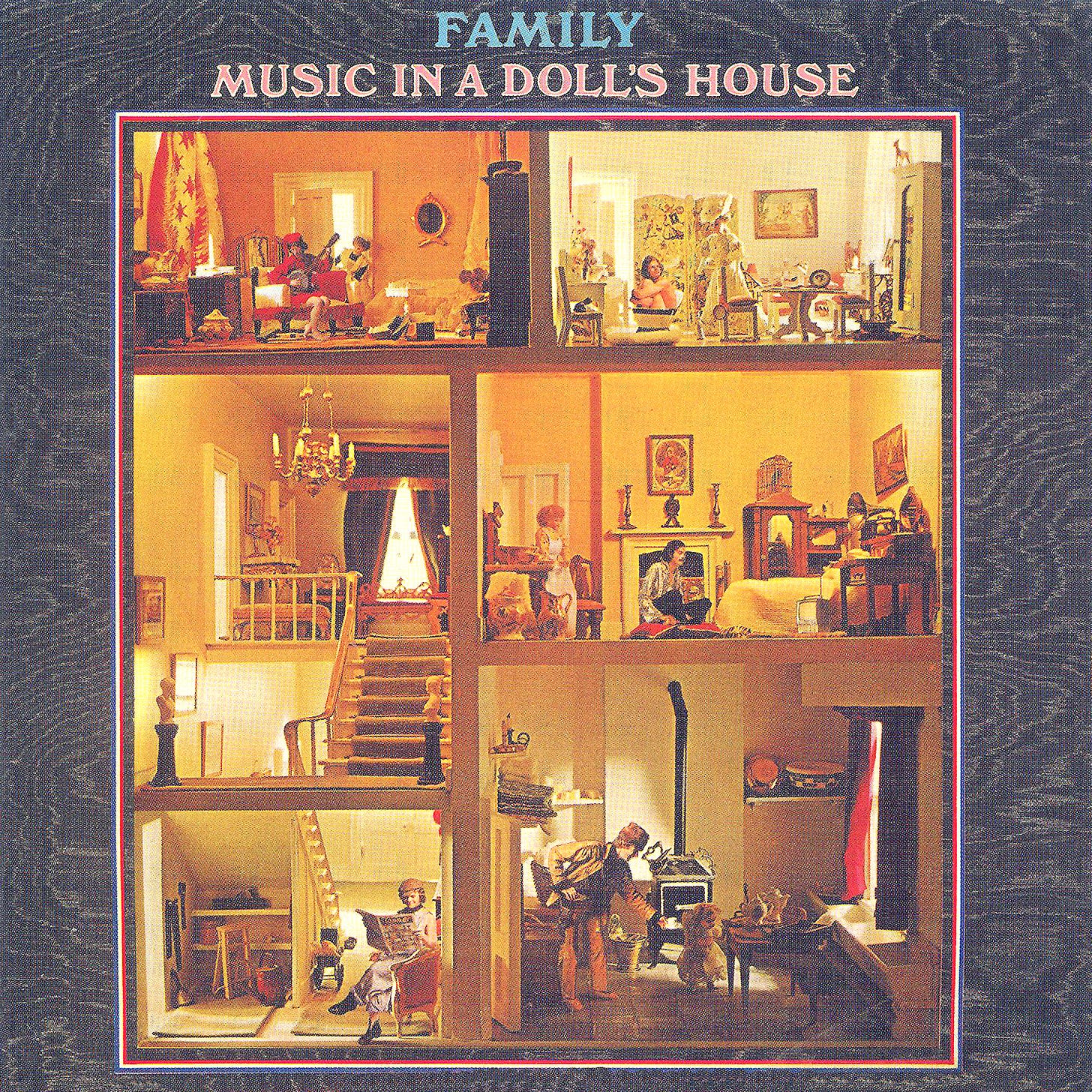

With a working title of “A Doll’s House” — a reference to the Ibsen play — it’s infamous for being the work of songwriters doing their own thing — often recording in parallel, and symbolised by the 4 individual portraits. Their only double album is darker, stranger and more individualistic than previous efforts. In addition to the dark overtones of the Ibsen play, it also suggests a miniature world, a series of vignettes, each locked in their own room, inhabited by strange characters, scenes and moods.

The working title was only abandoned when English progressive rock band Family got there first, and a quick look at their Music in a Doll’s House cover, hints at what a Beatles cover might have looked like.

In many ways it’s also John’s strongest Beatles album (‘Dear Prudence’, ‘Happiness Is A Warm Gun’, ‘I’m So Tired’, ‘Cry Baby Cry’, ‘Revolution 9’, ‘Good Night’, ‘Yer Blues’, ‘Everybody’s Got Something to Hide except For Me and My Monkey’, ‘Glass Onion’, ‘Julia’…). Put ‘Bungalow Bill’ to one side for a second and it’s a powerful string of John classics… melding confessional, dreamlike, subversive, urgent and depressive genres. All the feels! I’d take John’s White Album all day, every day.

It’s also one of the Beatles most Carrollesque confections. Not so much in terms of direct quotes and allusions, but rather in its stylistic mood, the rich and strange blend of nursery rhyme, sleep/dream, imagery and collage.

THE COVER

Of course, in abandoning the Doll’s House concept, The Beatles were nonetheless in search of a new move, something that would stand as a step on from the maximalism of Sgt Pepper and Magical Mystery Tour. Enter Richard Hamilton.

Hamilton’s cover concept for The Beatles has precedents in the evolution of conceptual art. Take Rauschenberg for example from 1951:

Or Piero Manzoni’s Achrome:

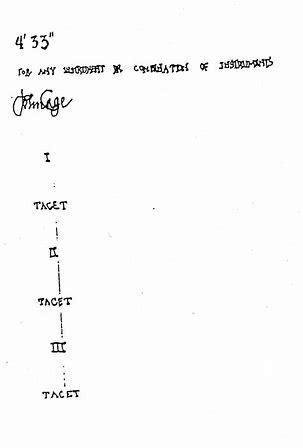

Or John Cage’s 4’33”:

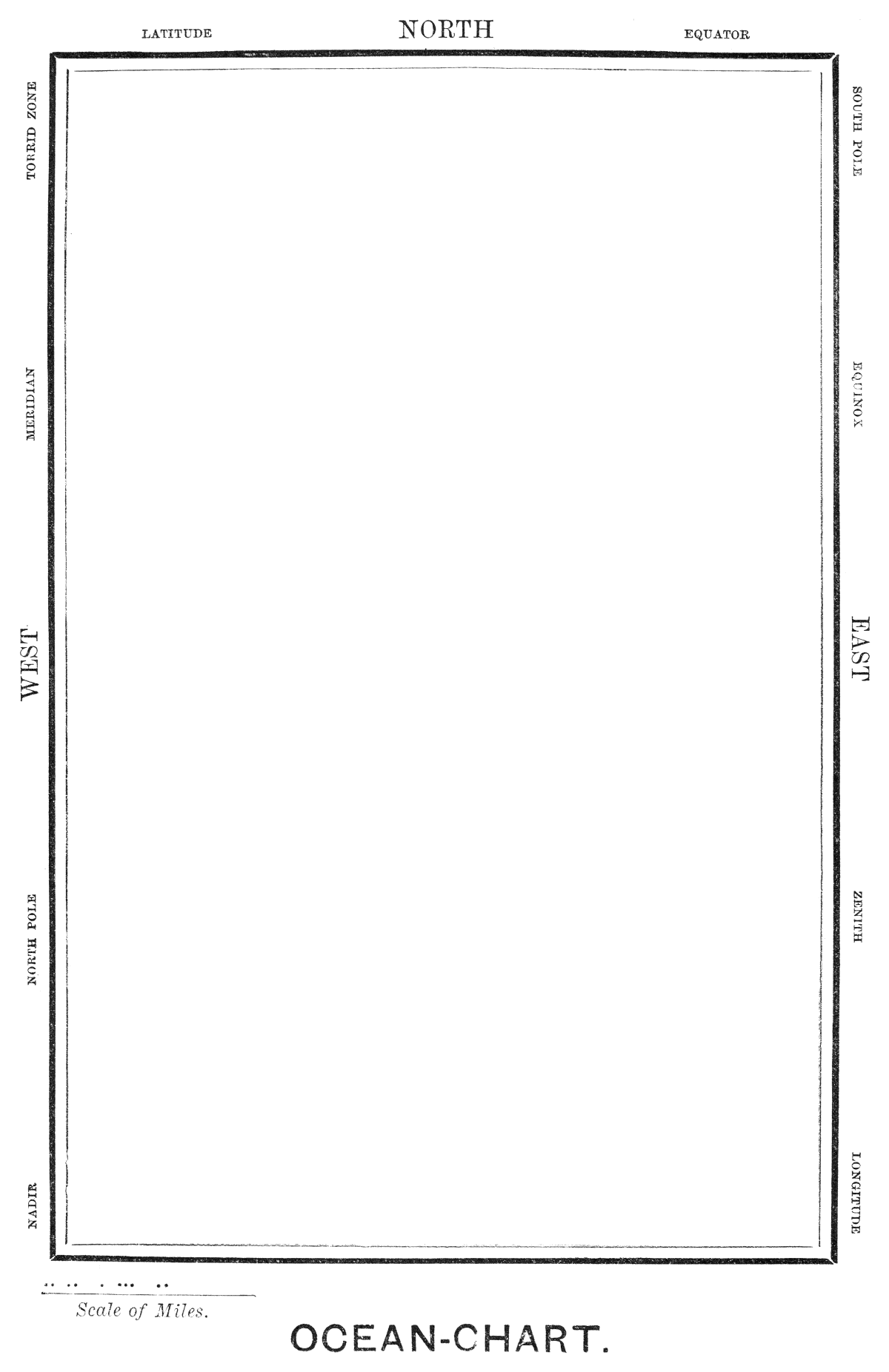

But as mentioned in my Cover Art post, the idea that a totally white cover could be inspired by Carroll is confirmed by Andrew Wilson too:

“Such a use of nothing might perhaps seem absurdly humorous — one precedent for Hamilton being the blank map, Ocean Chart, that appears […] in The Hunting of the Snark”

-Andrew Wilson “White on White” (White Album Deluxe Box Set book, 2018)

Negative space. The anti-concept. Very Carrollian. But what of the songs?

THE SONGS

Dear Prudence

Many of the White Album’s songs were written in, and inspired by events in Rishikesh, at the ashram of the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, immortalised on the Album in the sardonic “Sexy Sadie”.

‘Dear Prudence’, another case in point, takes the overt form of a dialogue with Mia Farrow’s sister, Prudence, as John and George attempt to lure her out “to play”, from her meditative isolation.

While it’s not often on most people’s lists of “top Carroll Beatles songs”, I agree with most of the critics who’ve tried to make a connection. Dear Prudence is in fact deeply Carrollian, a weave of elements that hold John’s Alice imaginary together.

Creeping hypnotically into view out of the end of ‘Back In The USSR’, the cyclical opening of Dear Prudence — with its “cuckoo clock” major third figure — immediately signals the kaleidoscopic feel of ‘Lucy In The Sky…’ and ‘I Am the Walrus’, underpinned by a droning D pedal that’s dreamworld incarnate.

The refrain “won’t you come out to play” is hardly coincidental. We’ll see later how McCartney raided the Lobster Quadrille’s “will you won’t you….” refrain for Helter Skelter, but I see here the same echo, not least because the insistent emphasis in the metre of Dear Prudence feels so in line with Carrollian song metre.

And then the command to “open up your eyes”. It’s another ‘invitation’ move.

There are also the nursery rhyme elements, that feel so appropriate for a song to a child figure trapped between waking and dreaming. To quote Jack, Fred & Tristram, “there are elements of nursery rhyme in the symmetrical melodic phrases that keep this song more in the realm of Lewis Carroll than something written in the foothills of the Himalayas.”1

“The clouds will be a daisy chain….” John sings, recalling both the “cloud” motif of later songs like ‘Imagine’ and ‘Across the Universe’, but also the opening scene of Alice in Wonderland:

So she was considering in her own mind, as well as she could, for the hot day made her feel very sleepy and stupid,) whether the pleasure of making a daisy-chain would be worth the trouble of getting up and picking the daisies, when suddenly a white rabbit with pink eyes ran close by her.

-Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865)

As is always the case with John’s songs, there’s a universal message — “and you are part of everything” — that transcends the specific trigger for the song.

Later — on ‘#9 Dream’ John will intone “through the mirror go round round”, and “round round round…” is also the insistent mantra underpinning ‘Dear Prudence’, doubled in deep backing vocals with the resolution a swampy, slithery turnaround that uses glissando in the same way Walrus did a year earlier.

Glass Onion

If ‘Dear Prudence’ is written as a dialogue with Mia Farrow’s sister, ‘Glass Onion’ is an act of provocative diversion aimed at conspiracy theorists and literary critics. The onion in the title evokes a strange image of something layered and simultaneously transparent, a perfect symbol for a song that openly layers puzzle upon puzzle:

I told you about the walrus and me, man

You know that we're as close as can be, man

Well, here's another clue for you all

The walrus was Paul-John Lennon, ‘Glass Onion’ (1968)

Paul has revealed that he also wore the Walrus mask during the filming of Magical Mystery Tour, so the diversion is also real. Self-referential IYKYK territory. Lennon builds each verse on references to previous Beatles songs, many with Carroll connections:

“I told you about strawberry fields”

“I told you about the walrus and me, man”

“I told you about the fool on the hill”

“Fixing a hole in the ocean”

It not only references ‘Walrus’, it also acknowledges the fact that ‘Walrus’ is itself referential, including echoes of ‘Lady Madonna’ and ‘Lucy’:

“See how they run like pigs from a gun, see how they fly”

“See how they fly like Lucy in the Sky, see how they run”

And it’s not just lyrics that call back to previous songs. The cello glissando parts recall the musical language of ‘I Am The Walrus’. It’s peak postmodern psychedelia.

Helter Skelter

Spurred on by reading about The Who, and how they’d made the loudest song ever, McCartney’s Helter Skelter is the most unexpected of the Beatles Carroll songs. And yet, as Paul says:

The verses are based on the Mock Turtle’s song from Alice in Wonderland:

‘Will you, won’t you, will you, won’t you, will you join the dance?

Will you, won’t you, will you, won’t you, won’t you join the dance?’John and I both adored Lewis Carroll, and we often quoted him. Lines like ‘She’s coming down fast’ have a sexual component, perhaps a little drug component too. A little darker.

-Paul McCartney, The Lyrics

It’s worth repeating that the Alice books are highly musical, not just because they contain songs — from the ‘Lobster Quadrille’ to the ‘Mock Turtle’s Song’ — but also because the books are downright noisy, full of clattering, shouting, and word sounds. Perhaps not such strange bedfellow after all.

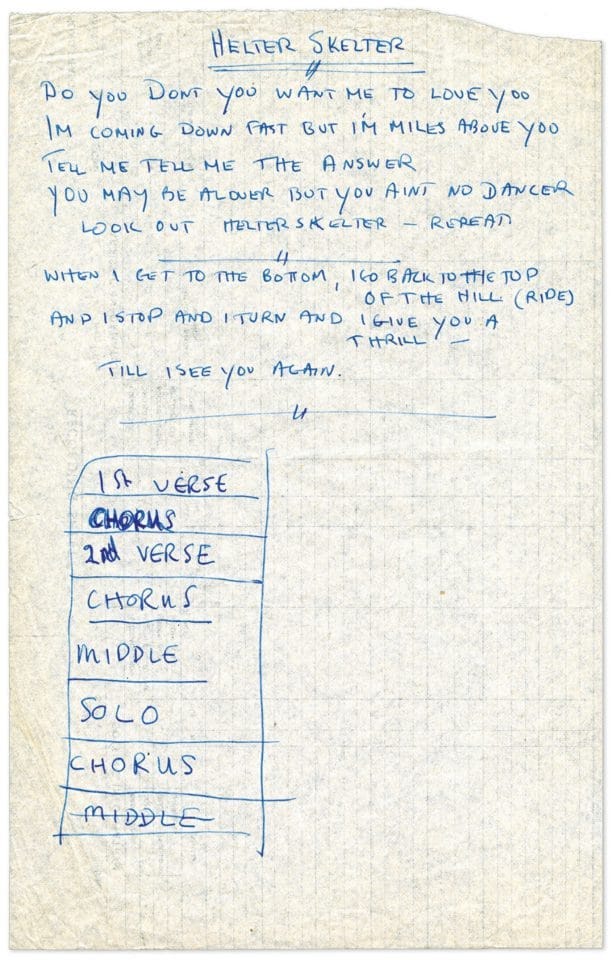

Anyway, here are Paul’s handwritten lyrics, showing how central the “verses” from the ‘Lobster Quadrille’ are to the conception of the song.

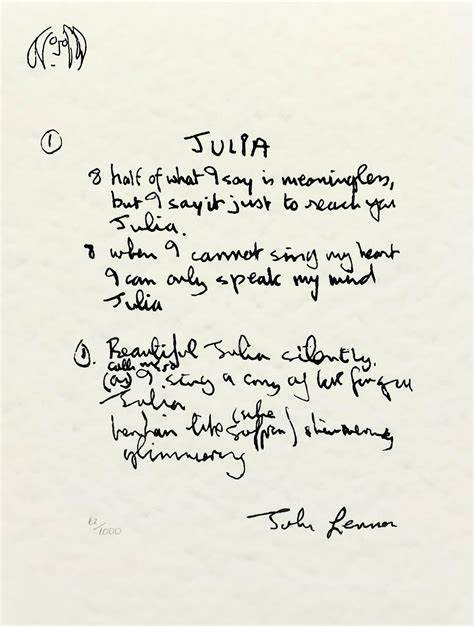

Julia

“Half of what I say is meaningless…” is how John begins his ode to Julia.

It’s a conversation across time, to a mother he lost too early, a song of loss, of unfinished and inexpressible feelings. But it’s also an affirmation, a “song of love”. While the feelings aren’t fully formed, and while language is insufficient to fully express anything, still “…I say it just to reach you, Julia”.

Lennon’s maturing voice is increasing direct and personal, but it’s the same ethos as ‘Lucy’ - a yearning, pleading, cry for salvation, for a woman — Alice-like — to guide him on his journey. The imagery uses the same kinds of metaphorical move we find in ‘Lucy’ — “the girl with the sun in her eyes” - only simpler, more natural, less psychedelic:

“Seashell eyes”

“Windy smile”

“Morning moon”

“Sleeping sand”

“Silent cloud”

A simple song to his mother? Nothing is ever that simple with John.

"Julia was my mother. But it [the song] was sort of a combination of Yoko and my mother blended into one."

-John Lennon

The fact that Yoko name means “ocean child”, only goes to reinforce the idea of a holy trinity of Alice/Lucy/Julia/Yoko in John’s imagination.

Cry Baby Cry

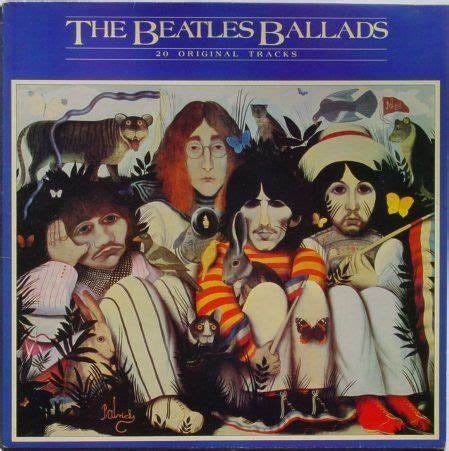

It’s often claimed that John Byrne’s painting that ended up on The Beatles Ballads was the original commission for A Doll’s House, and not only does it feel very Carrollesque, it’s in the same style as the cover for 1971’s HMS Donovan, an album that opens with settings of ‘The Walrus & The Carpenter’ and ‘Jabberwocky’.

Yet reliable sources — not least essays in the official White Album Deluxe boxset — have poo-pooed the claim, pointing out that it was instead destined for the Beatles Illustrated Lyrics instead. Frankly I’d never have bought it anyway; it just doesn’t fit the Doll’s House concept.

And so to my new discovery.

The White Album deluxe box set, issued in 2018, contains an enigmatic photo of what must be an early set list and cover concept. Against a running order that contains most of the tracks that formed the final White Album — but also ‘Polythene Pam’ and ‘Maxwell’s Silver Hammer’ — are handwritten notes for what I assume were to be vignettes for a Doll’s House cover spread.

And tellingly — against ‘Cry Baby Cry’ — is the phrase “Alice fancy dress party on lawn”. While it’s totally true that the direct references in the song echo the nursery rhyme ‘Sing a Song of Sixpence’, Wonderland is full of nursery rhyme imagery, and I think John unquestionably had Alice in mind — not just nursery rhymes in general — based on this new discovery.

“The King of Marigold was in the kitchen

Cooking breakfast for the queen[…]

The duchess of Kircaldy always smiling

And arriving late for tea”-John Lennon, ‘Cry Baby Cry’ (1967/8)

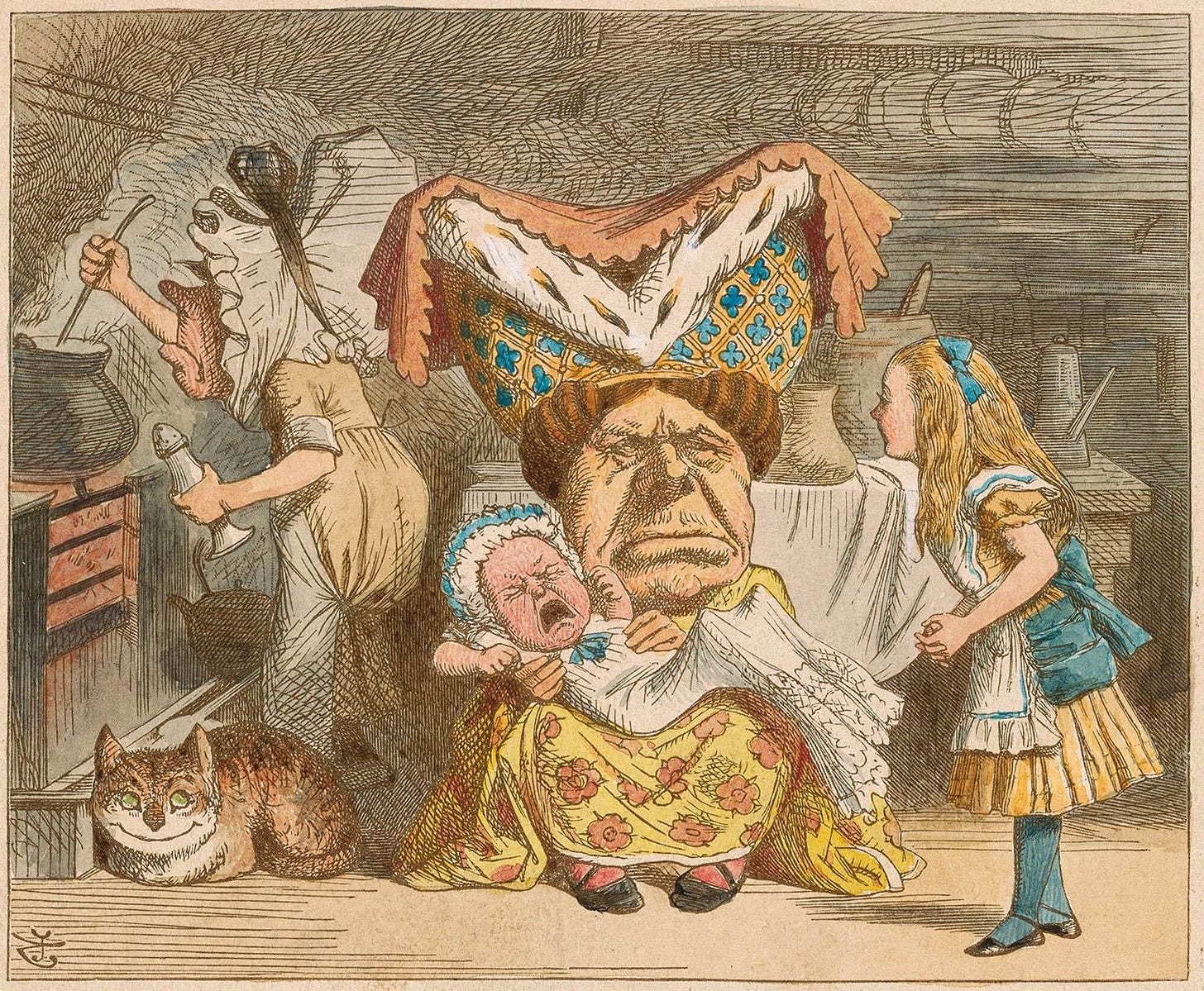

While we also know, from Hunter Davies, that ‘Cry Baby Cry’ took a line from an advert (“Cry Baby Cry, make your mother buy”) and changed it to “make your mother sigh”, the theme of crying recalls the crying baby in Wonderland:

The crying trope also shows up in the Beatles work as the “pool of tears” (AIW, ch2) in Paul’s ‘Long and Winding Road’ and, I’d argue, John’s “pools of sorrow, waves of joy” from ‘Across the Universe’.

Looking for a second at the harmonic structure of ‘Cry Baby Cry’, we find another instance of Lennon’s trademark chromatic descending patterns that always set my Alice alarm bells ringing, as I believe they echo the kaleidoscopic / circling ‘dream harmonies’ that show up — albeit in different guises — in ‘Lucy in the Sky…’, ‘I Am the Walrus’ and ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’. QED?

Lennon, in his dismissive phase in 1980, described the song as “a piece of rubbish”, but it’s still one of my favourites, and spawned some fabulous covers, not least by Throwing Muses. It’s also true I think that Lennon often tended to dismiss songs that others have found the most revealing. Alan Pollack’s notes on the song frame it as “anti-lullaby”:

In a world where the archetypal lyrics for a lullaby are "hush little baby, don't you cry", John's title phrase here combined with "she's old enough to know better" conjures up some kind of perverse Anti Lullaby.

-Alan Pollack 2

Chris Matheson, co-author of the Bill & Ted films, gives an interpretative masterclass in which he digs into the Carroll aspect of Lennon’s song…

“For me, the Lewis Carroll thing, it's not just the, some people think of that as like, well, it's the wordplay, it's the cleverness, it's the puns, it's all of that, right? And to me, that's not what makes Lewis Carroll interesting. That's not what makes Lewis Carroll magnificent. That's not really ultimately what John was responding to. I think what he's responding to is the darkness that is inherent in the two Alice books, which are my favourite books, actually. And it's that beautiful, strange, slightly disturbing quality of a children's story. And in Cry Baby Cry, a children's song that is really steeped in darkness and pain and longing and loneliness. […] something really true and stark.

- Chris Matheson, My Favourite Beatles Song: Cry Baby Cry

Chris argues that not only is it an anti-lullaby — commanding the baby to cry — but that the baby is Lennon, weeping for his lost mother. And that the “seance in the dark” from the last verse speaks to Lennon’s desire to bring her back. That the song segues into Paul’s fragment “can you take me back”, makes perfect sense in this context. I highly recommend a listen, here:

Revolution 9

I won’t make a big play for the White Album’s most odd and conceptual track as Alice-inspired. I say this because really it’s a John & Yoko song, and more influenced probably by her artistic practice.

And yet, it does extend the tape-loop collage approach that dominates ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’, and I do think that sonically, that brings us in line with my notion of the Alice Code as a creative practice based on jumps and blends, loops, reversal and varispeed, and more.

But as I’ve said before, I really don’t want to claim everything as Carrollesque. So for this week, let’s leave it there.

The White Album. Some like to imagine — as George Martin had wanted — a stripped back, single album. Many — like Geoff Emerick — focus on the swearing, in-fighting, dysfunctional mood they claim dominated the sessions. Countless critics repeat the notion that it’s the sound of a band falling apart. I do think there’s some truth to it, but frankly, who cares. It’s a rollercoaster of a ride, and a true treasure trove.

Musical identity crisis, or masterpiece. I know where I stand.

How about you?