18 Cover Art pt1: the Albums.

In which '60s designers get to channel their inner Alice to create 'total' artworks.

Every week in Alice & The Eggmen, we look at the relationship between the worlds of Lewis Carroll and The Beatles. It’s a complex and often subtle weave, and this week’s a great case in point, since we’re not talking lyrics or music, but artwork.

And that opens the door again to the whole field of visual development — especially via the surrealists, and conceptual art — that converges in the 60s in curious ways, that I’d argue owe a huge debt to Alice, and also influenced the people who made the Beatles recorded work into ‘total’ works of art.

So in this episode we’ll be looking at Beatles albums with an Alice-influence:

Rubber Soul (1965)

Revolver (1966)

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967)

Magical Mystery Tour (1967)

The Beatles (aka The ‘White Album’) (1968)

Yellow Submarine (1969)

Some of it’s obvious and attributed. Much of it’s my interpretation. And yes, at times you’ll be wondering whether I’m making too much of some fragments, but if you buy into my ‘Alice Code’ idea, that Carroll’s legacy isn’t just specific images, and characters, but a broader creative process, I hope it’ll make a lot of sense.

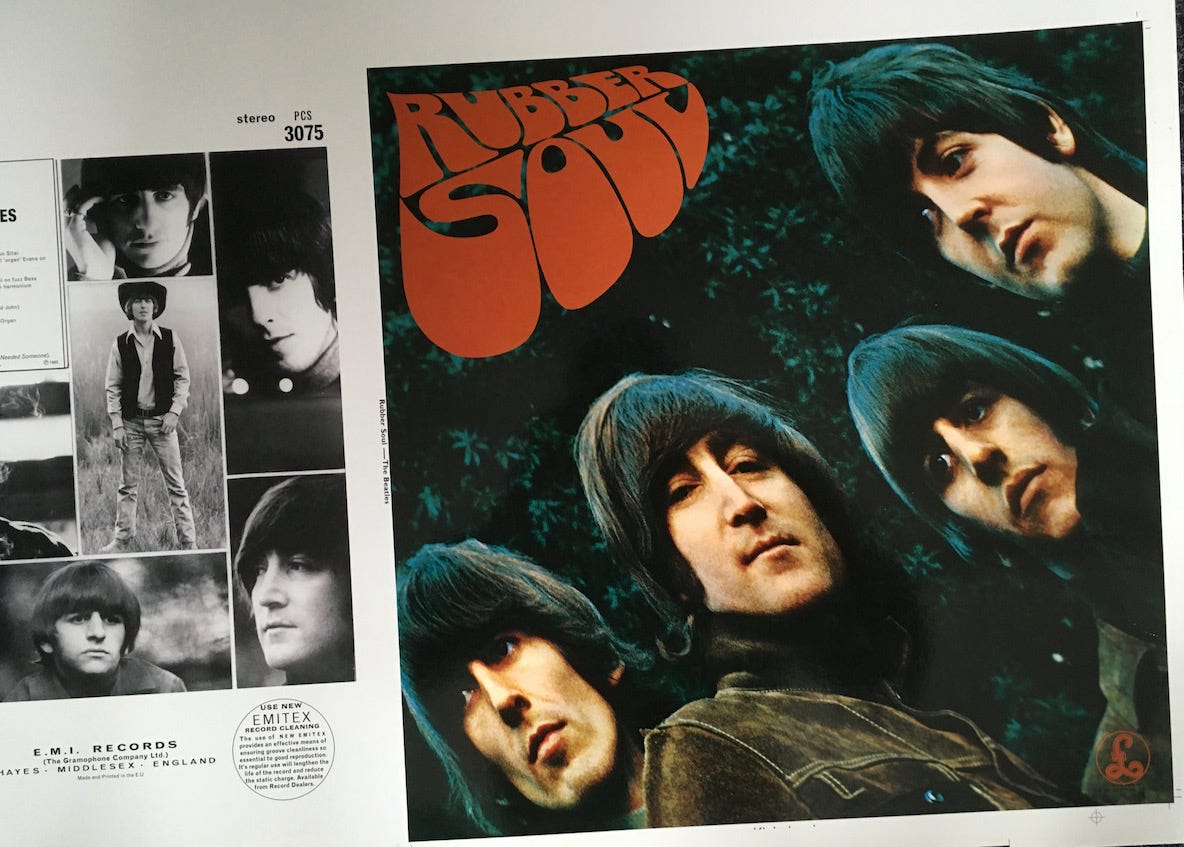

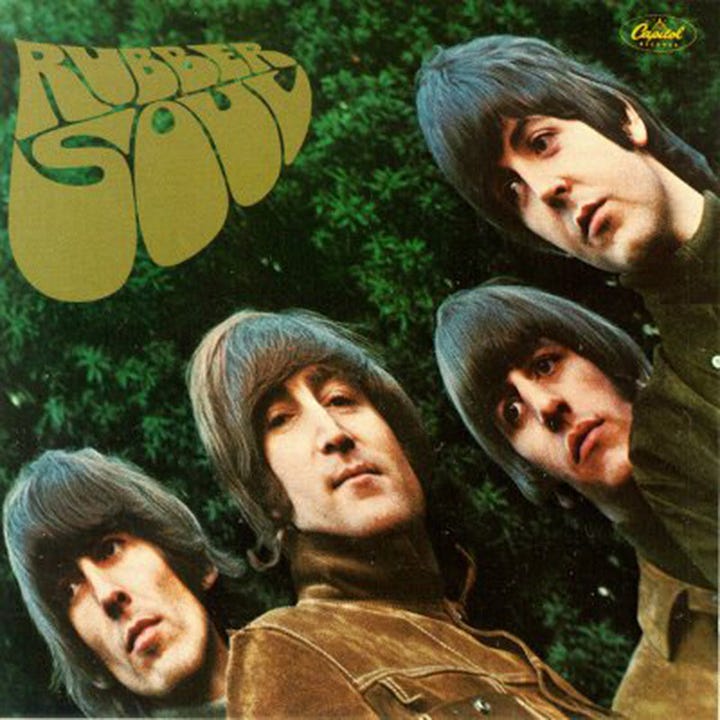

Rubber Soul (1965)

Rubber Soul marks a clear turning point, thematically, lyrically, musically and visually.

It’s the sitar on Norwegian Wood, the overtly angst-ridden Nowhere Man, the double-speed piano on In My Life. George Martin says they’re now ‘recording artists’ rather than a band recording live performances, and it’s a shift from smiling mop-tops to warped aesthetics.

While Robert Freeman, who’d photographed them for previous album covers, took the photo, it was in presenting it to The Beatles — projected onto card — that the famous ‘accident’ happened and the projected image became strange and elongated. ‘That’s it!!!’ The Beatles proclaimed, excitedly.

The title of the album was a play on ‘plastic soul’ — a derogatory term used by black musicians to characterise white bands playing soul music — while the logo was elongated to match the play on words (another Carrollian trait).

We can see the shift from original, realistic, shot to the distorted print below. It’s a shift in optical perspective that matches their shift in musical and lyrical perspective.

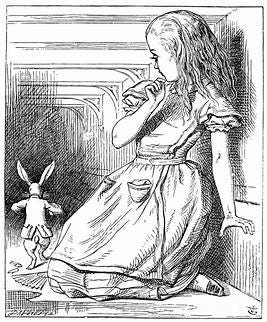

While no-one owns perspective shifts, least of all Lewis Carroll or his collaborators, the ‘low angle shot’ is reminiscent for me of many of the visualisations of Alice’s perspective in Wonderland and beyond.

But it’s really with the next album — and the more substantive experimentation it ushered in — that things start feeling really strange.

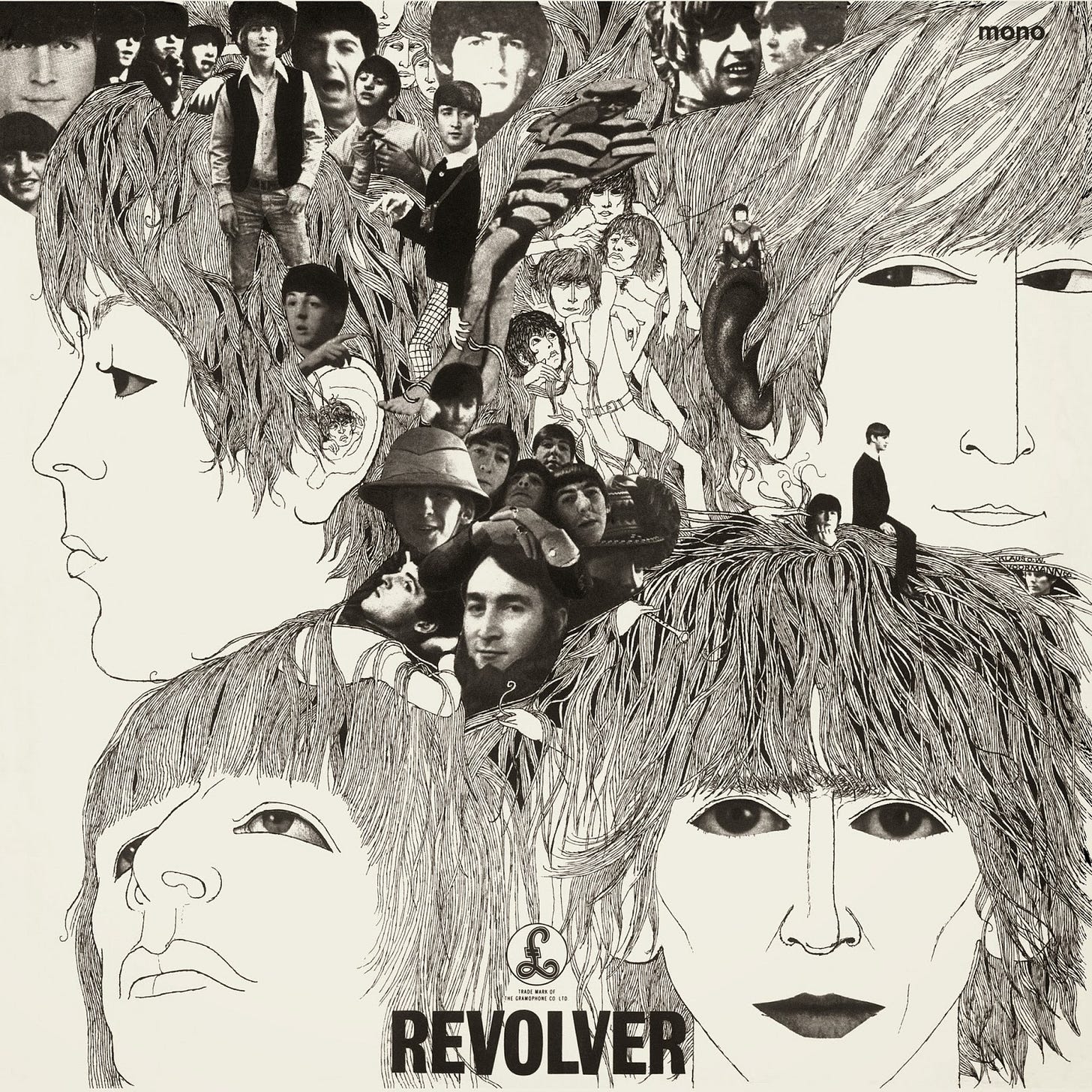

Revolver (1966)

If Rubber Soul took 4 weeks to record, Revolver marked another gear shift, with The Beatles clocking up 4 months’ work. And ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ — in particular — is a triumph of sonic adventure, from reverse tape loops and varispeed, to the use of the Lowrie cabinet to achieve John’s distant, woozy, vocal.

This sonic departure took Klaus Voorman — The Beatles’ friend from their Hamburg days, and whom John asked to get involved — by surprise, and set the stage for a ‘levelling-up’ of the visual approach. He sought an aesthetic that could capture the darker, trippier, atmosphere captured in the studio.

As Voorman recalls…

[John] invited me to come down to the studio and I listened to the tracks for what would become the Revolver album. At first, my impressions of the music they played me was that it was just incredible. It was just really hard to explain. It was so far ahead of whatever any pop group had done before. This was going into Stockhausen and other kinds of avant-garde music, and suddenly you had the Beatle fans from the early days and now you had this new music. I didn’t know if they’re going to accept it or not. It was really a big step into the future.1

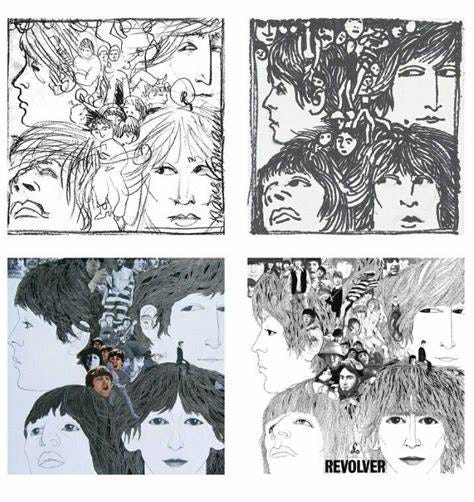

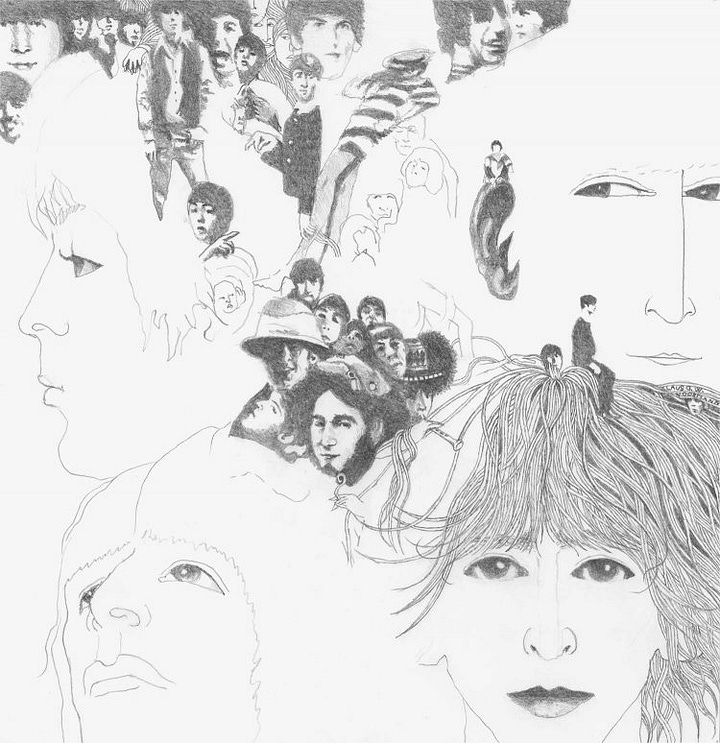

It led Voorman to explore an amalgam of styles — primarily the collage approach of Kurt Schwitters, but equally multi-dimensional elements that deconstruct images of the four members to create a kaleidoscope of scale.

Giant Beatles heads reveal smaller Beatles heads nestling in the hair, and emerging from in-between each other. Singular, stable, fixed, identity (a 4-man headshot) is swapped for multiplicity and fluidity, recalling the key uncanny feeling of Alice and her relationship with her own identity in Wonderland.

"Who are you?" said the Caterpillar.

This was not an encouraging opening for a conversation. Alice replied, rather shyly, "I—I hardly know, Sir, just at present—at least I know who I was when I got up this morning, but I think I must have been changed several times since then."

-Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Ch.5: Advice from a Caterpillar

And so to the final, iconic, image that overlays not just pencil and photography (down to the cut out eyes for George) but also scale-switching and optical ambiguity. You just don’t know where to look - the gaze is perpetually displaced.

Some have assumed — as I once did — a clear link to the Beardsley ‘66 exhibition at the V&A, but Voorman both admits the influence and denies that the exhibition triggered it.2

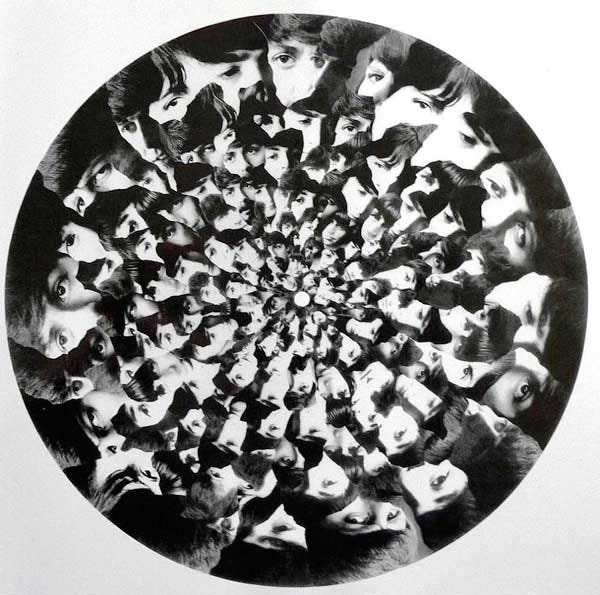

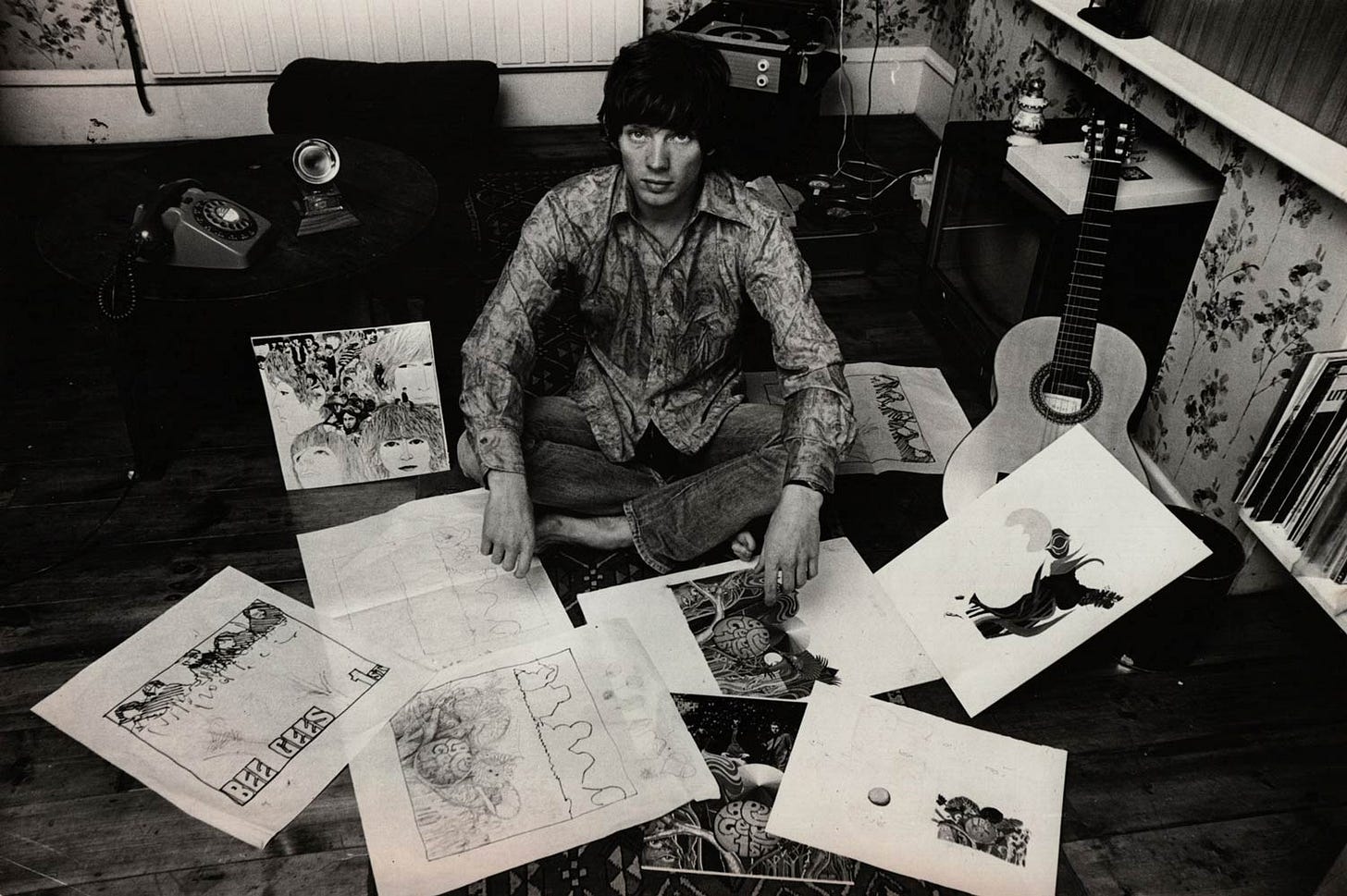

But it’s not just the final artwork that shows the direction The Beatles were exploring. Another candidate was this beauty:

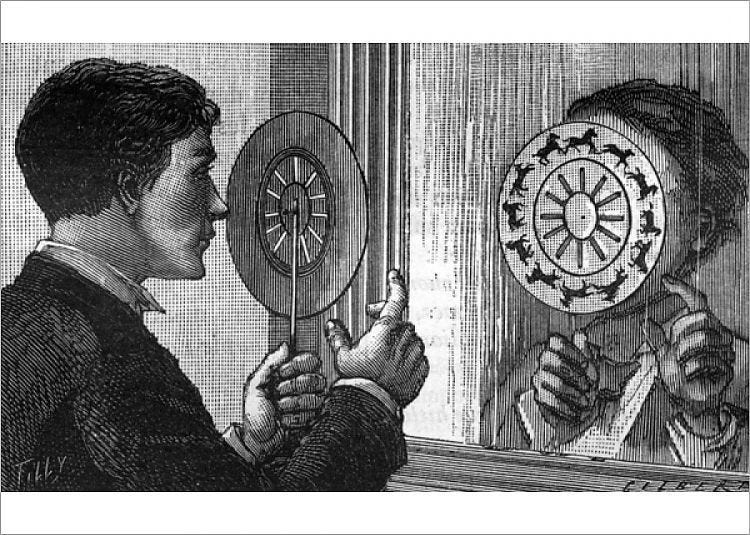

We have to imagine this turning as the LP plays to remind ourselves of the intended effect. It tips the hat to Victorian optical experiments and things — I believe — like the Phenakistoscope and the Zoetrope:

And how fascinating is this mirror Zoetrope image?

But equally, swirling, falling, imagery is how we visualise Alice’s experience in Wonderland. These distorted, fish-eye style representations are common in the way illustrators have chosen to depict the fall down the rabbit hole or the house of cards, key transition moments in the Alice narrative.

Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967)

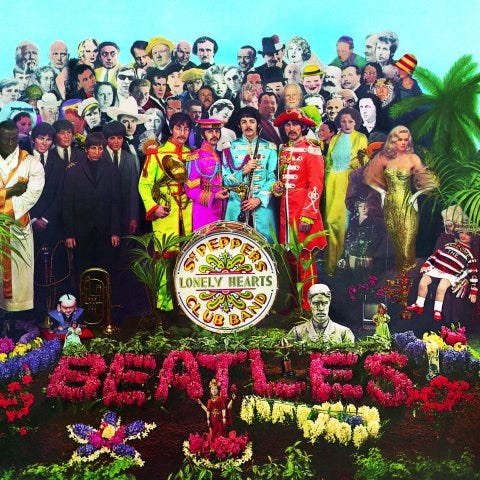

We’ve already covered Sgt Pepper, but it’s the big one, and worth repeating: Carroll is on the cover, one of the pantheon of historical and cultural heroes The Beatles selected to stand behind them.

The day-glo Beatles stand next to their black-and-white mop-top selves in another symbolic play on identity, representing the shift in direction. But of course it’s also ‘not’ the Beatles we see, it’s the Beatles playing Sgt Pepper’s band.

In the juxtaposition of characters and colours, the cover functions as an invitation to step into what I’ve called a sonic Wonderland, with a gatefold sleeve, printed lyrics, and a set of accessories in the form of cut-out lapels and moustaches. The album becomes a portal, designed for listener journeys, not dancing or background listening.

It’s always instructive to look at the rejected covers, as we’ve seen with Revolver, and in the case of Pepper it’s The Fool’s fantasy-land that was an early commission.

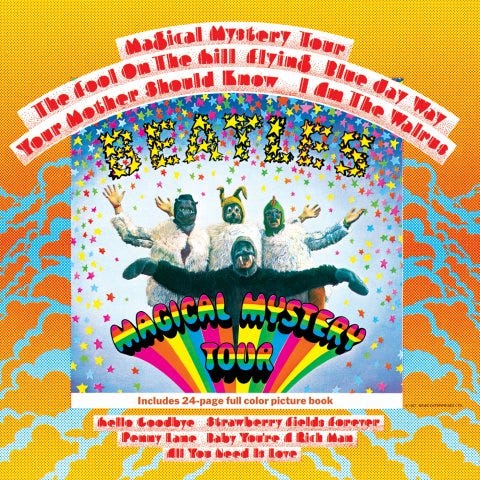

Magical Mystery Tour (1967)

McCartney’s post-Epstein folly or psychedelic masterpiece, Magical Mystery Tour is a curio in this list, not least because it’s really a double EP (6 new tracks bolstered with previous singles), and not an album at all.

Putting that aside for a minute — from the very notion of a magical journey, to the tarot-meets-nonsense ‘Fool On The Hill’, to ‘I Am The Walrus’ that gives the cover its central image — this is a 60s nod Alice in more ways than one.

Anthropomorphisation — animals as people or vice-versa, perhaps — is enshrined in the refrain of ‘I Am The Walrus’, a clear and avowed Carrollian tribute to ‘The Walrus And The Carpenter’.

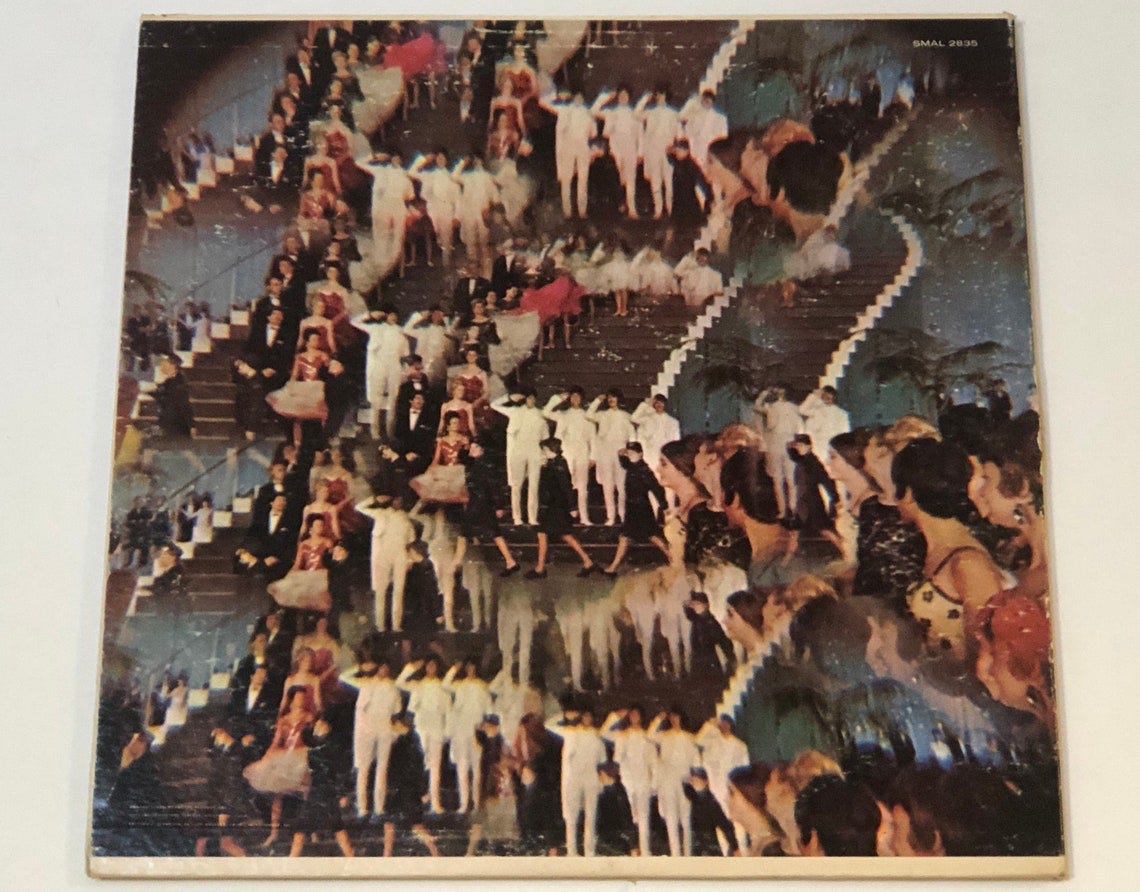

And wherever we see mirrors, we are right to suspect Looking-Glass influences. So let’s not forget the rear cover image, a riot of reflection and distortion:

As in much of the Beatles’ output, there’s a complex and subtle integration of memory, tradition and culture into rock and pop novelty. That’s musical, for sure, but it’s also visual. And the way this kaleidoscopic image takes a throw-back photo of the Beatles in white tailcoats, makes the familiar unfamiliar. ‘Very strange’ sings Paul in Penny Lane. We are definitely in curiouser and curiouser territory.

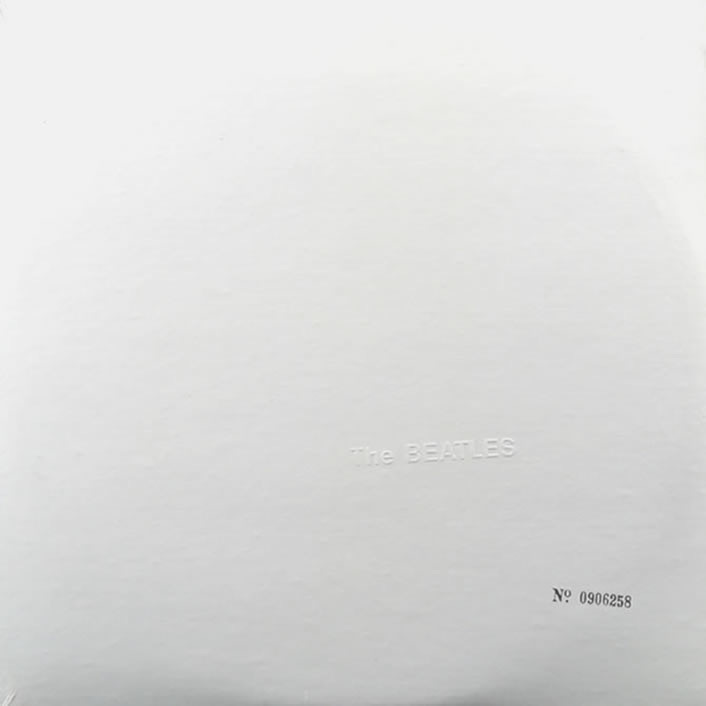

The ‘White’ Album (1968)

The nameless / eponymous The Beatles was originally going to be called A Doll’s House, perhaps echoing the fragmentary set of songs-as-rooms. It’s not an album with a clear, cohesive, sound, narrative or logic so much as a series of vignettes, large and small, covering all musical styles. It blends homage and nostalgia (‘honey pie’), heartfelt folk (‘Julia’, ‘Mother Nature’s Son’), biting satire (‘Piggies’), oblique social commentary (‘Blackbird’), lullabies (‘Goodnight’), proto-metal (‘Helter Skelter’), and wild experimental sound-collage (‘Revolution 9’).

It’s also an album with a high Carroll-count:

‘Helter Skelter’ recycles the “will you won’t you’ chorus of the Mock Turtle’s Song

‘Glass Onion’ affirms that ‘the Walrus was Paul’ — in a classic piece of Lennon misdirection — and also calls back to “Lucy in the Sky”

‘Julia’ speaks of “sea-shell eyes” and other imagery that’s in the ‘Lucy’ “marmelade skies” and “celophane flowers” vein.

‘Revolution 9’ plunges us into a disorienting, noisy, Wonderland of sound snippets and images.

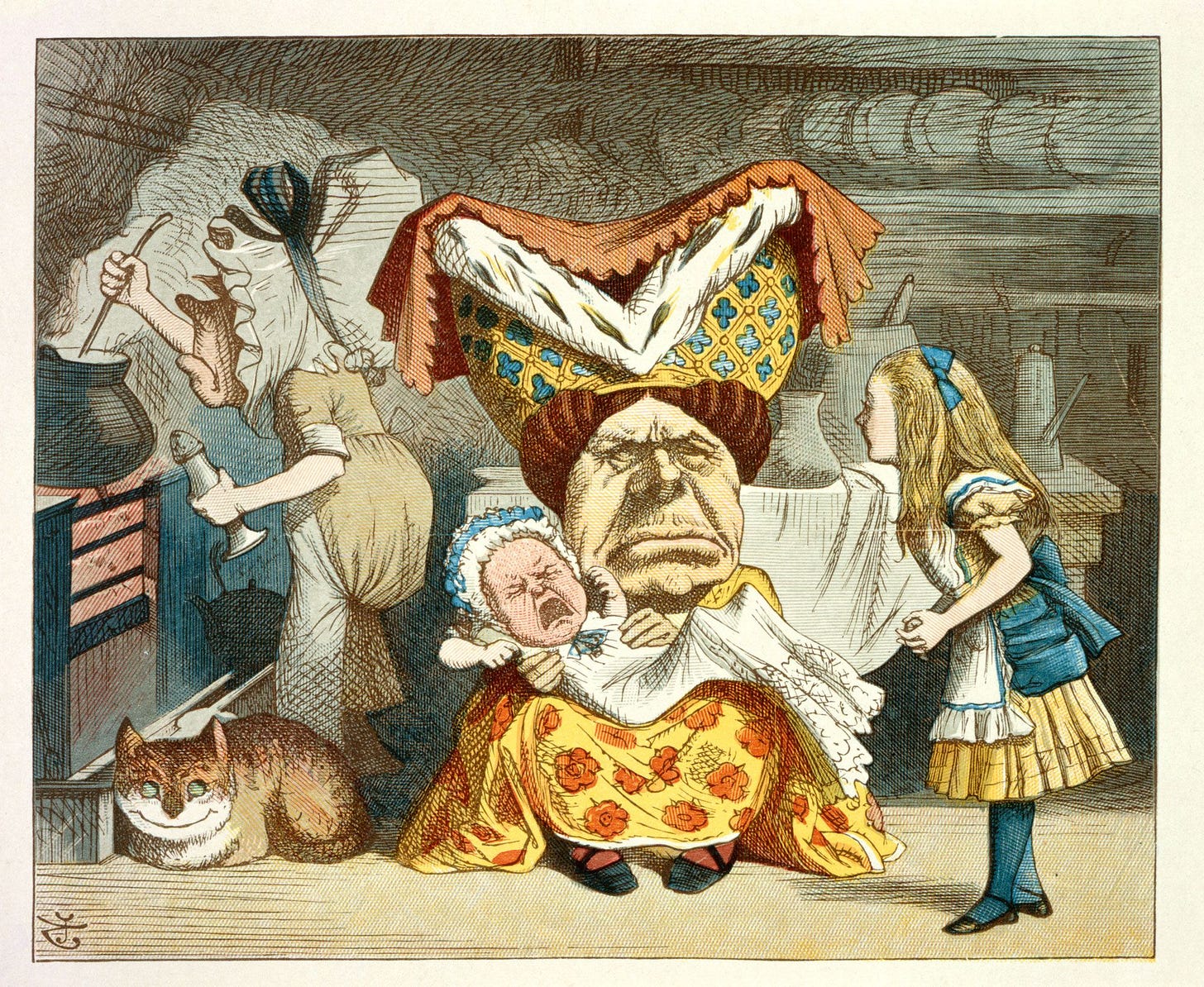

‘Cry Baby Cry’ riffs on nursery rhymes, like ‘Sing a Song of Sixpence’ (with its “king” in his “counting house”) and let’s not forget that crying babies are a feature of Wonderland too.

Another band - Family - got there first with Music in a Doll’s House, however, so The Beatles commissioned Richard Hamilton to come up with something totally different.

Paul McCartney requested the design be as stark a contrast to Sgt Pepper’s day-glo explosion as possible… he got it!

-Richard Hamilton3

Some have “speculated whether Hamilton was influenced by the Apple Shop mural [which] originally showcased a psychedelic mural by the collective The Fool [but which was] overpainted in white by May 1968”.

Whatever the truth of the story, Hamilton’s use of negative space, a cover that’s perfectly white, with white embossed lettering, feels like the height of ironic postmodernism, or — depending on how you see it — a perfect and pristine piece of serious concept art.

This artwork needs no commentary, perhaps. No overarching concept. No message. It’s saying something different: You judge. Make it yours. It’s the epitome of self-confidence for a band who were also on the brink of dissolution, seeking something to hold it all together?

But we could also see it as the ultimate mystery, a white mirror inviting you inside, to an inner world. Another portal in a world of sonic portals. And while there’s no direct link, it does make me think of that classic Carrollian ploy/joke, the Bellman’s map of the ocean, “a perfect and absolute blank”, in The Hunting of the Snark (1876):

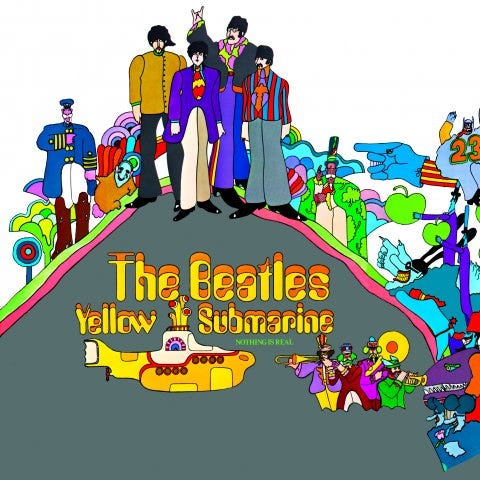

Yellow Submarine (1969)

Contracted to produce another movie that they had no appetite to make, the Beatles loved the idea of outsourcing an animation they wouldn’t have to appear in. But although Yellow Submarine was written, animated and voiced by others, they still had a big hand in the concept, and Yellow Submarine reprises many of their most Carrollian numbers from ‘Nowhere Man’ to ‘Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds’, not to mention the title song.

The idea of “_______land” as a device makes Wonderland and Pepperland, the setting for the movie, also feel like close cousins. While acknowledgement of the debt to Carroll is less explicit here, Wonderland is a word that even The Beatles current marketing uses to sum up the feeling of Yellow Submarine.

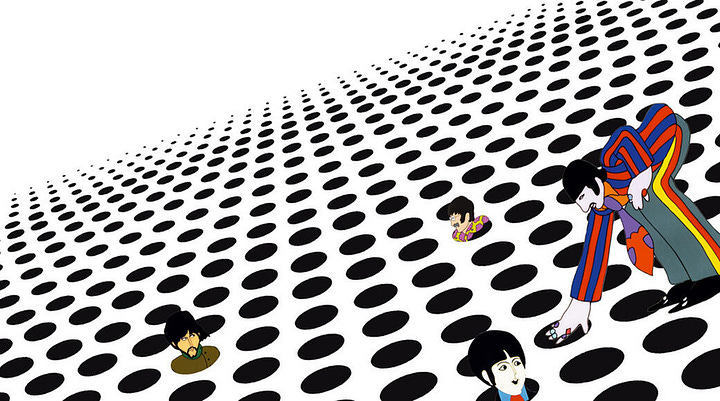

And the cover summarises the mood and characters:

This should come as no surprise. We know that the song itself was embellished with contributions from Donovan, who has explained that it came easily to him because of his deep knowledge of Victorian culture, fairy tales and nonsense verse.

And Wonderland tropes are all over the movie.

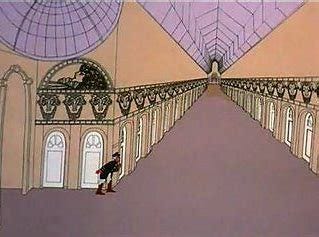

Who doesn’t love this early painting by Dorothea Tanning, with its strong whiff — I think — of Alice in the “long low hall” down the rabbit hole…

There were doors all 'round the hall, but they were all locked; and when Alice had been all the way down one side and up the other, trying every door, she walked sadly down the middle, wondering how she was ever to get out again.

-Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland Ch.1

When we see Tanning’s work we’re (partly) reading a semiotic code of locked doors, portals, and hallways as metaphors for the unconscious that, once seen, really can’t be unseen. I see a direct lineage with things like Yellow Submarine:

But we also have the Queen of Hearts-like Chief Blue Meanie — shrieking ‘kill them all’ (like ‘off with their heads’) as well as his aggressive flying glove, a terrifying bully.

There are green apples that recall the Apple Corps apple (which we know comes from Magritte and Carroll-inspired surrealism) and also strange, but loquacious companions, like Jeremy Hillary Boob, the Nowhere Man — uttering statements like ‘I am an Englishman, although I’m not’ or ‘the footnotes grow on trees’ — that I feel Carroll would have been proud of.

And finally, the ending — in which Pepperland fades into the real Beatles waving — closes the loop. Back into the ‘real world’. Hello again, kitty!

[…]

In the final albums, Abbey Road and Let It Be, the Carroll influence dissipates. We still find quotes for sure. ‘The Long And Winding Road’, for example, contains these beautiful lines:

The wild and windy night

That the rain washed away

Has left a pool of tears

Crying for the day

‘The Pool of Tears’ is chapter 2 of Alice in Wonderland, and I can’t help spotting some cross-contamination in John’s line in Across The Universe, also on Let it Be:

Pools of sorrow, waves of joy are drifting through my opened mind

Possessing and caressing me

But the ethos is much more “getting back” to something more grounded, earthy, real, as the wild ride of ‘60s psychedelia and post-68 disillusionment brings the decade to a close.

Next week we’ll jump into the solo work to see what we can spot there. Will we, won’t we find anything? I wonder.

GM: Was there any particular artist or artwork that you had in your mind to inspire you? Was Aubrey Beardsley an influence?

KV: He certainly was, but he’s not the only one. When you think of a collage, I was thinking of (Kurt) Schwitters. There’s lots of artists I was thinking of, but not in particular one person. Some people say, “Oh, you must have gone to that exhibition of Bearsdley, but I didn’t even go there. I love Beardsley. He’s fantastic. But he was not the inspiration for me with that style.