13 Swinging Alice (LDN67/8)

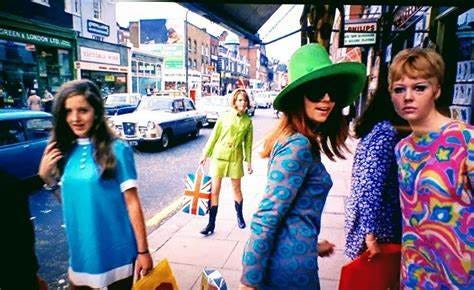

Art, music & fashion in the mid to late '60s, as psychedelia turns the colour on.

Each week in Alice & The Eggmen I trace the subtle, and sometimes not so subtle, links between Lewis Carroll and The Beatles.

In previous posts we’ve looked at Californian psychedelia — how headshop culture, blacklight posters by East Totem West, Ken Kesey & his Merry Pranksters, LSD and Jefferson Airplane’s ‘White Rabbit’ cemented Alice as the symbol of a new counter-culture consciousness; peeking behind the curtain to glimpse a world more real than physical reality.

But today I want to focus on the other epicentre of 60’s culture - ‘Swinging’ London. It’s the focus of the world, and home to The Beatles. And maybe it’s because I’m a Londoner, but I’m excited to dive into English culture and psychedelia, a different tradition, a different take on Alice, and how that became a post-war cultural bath, that the Beatles were both steeped in, and shaped in turn.

And of all the years in that decade, it’s 1966-1968 I want to zoom into, not least because there’s a feeling, a golden feeling that — for those who were there — seems to cast its warm glow onto the proceedings, especially in 1967:

The year 1967 seems rather golden, […] it always seemed to be sunny and we wore far-out clothes and far-out sunglasses. Maybe calling it the Summer Of Love was a bit too easy, but it was a golden summer.

-Paul McCartney

I’m glad McCartney acknowledges the ‘bit too easy’ part since the reality of most people living in the UK in the mid Sixties — as I know from interviewing my parents, aunts and uncles — was not all Carnaby Street and Blow-Up.

We have to remember that, even in 1967, “the BBC was still screening The Black & White Minstrel Show. Homosexual acts were partly decriminalised […] Britain was fighting a bloody colonial battle in Aden, unmarried women might still be refused the pill” and that “The Saint or The Avengers continue to peddle a 1960s myth precisely because they were shot on colour film as opposed to countless shows that were recorded on black-and-white video tape, only to be wiped a few years later”.1

And yet, 1967 was the year that the BBC switched the colour on, with Wimbledon:

Of course the word ‘golden’ also evokes Abbey Road’s ‘Golden Slumbers’, a carefree dream-state that captures so perfectly the end of the decade and the end of The Beatles (in retrospect and with a huge apology for anachronism). It’s also redolent of the optimism of ‘Penny Lane’, with its “blue suburban skies”.

And for Alice afficionados, it’s also a word laden with meaning, evoking the boat trip — which we celebrate as Alice Day (July 4th) — where Carroll entertains the Liddell girls with fanciful tales and which becomes the opening poem of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland:

All in the golden afternoon

Full leisurely we glide;

For both our oars, with little skill,

By little arms are plied,

While little hands make vain pretence

Our wanderings to guide.-Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865)

The long and winding road to 1967…

The mid-’60s mark a cusp, I think; a reappraisal, and reinvention, from school prize-giving classic, regional theatre staple and popular culture stalwart to subversive counter-culture reference point. But how did we get there?

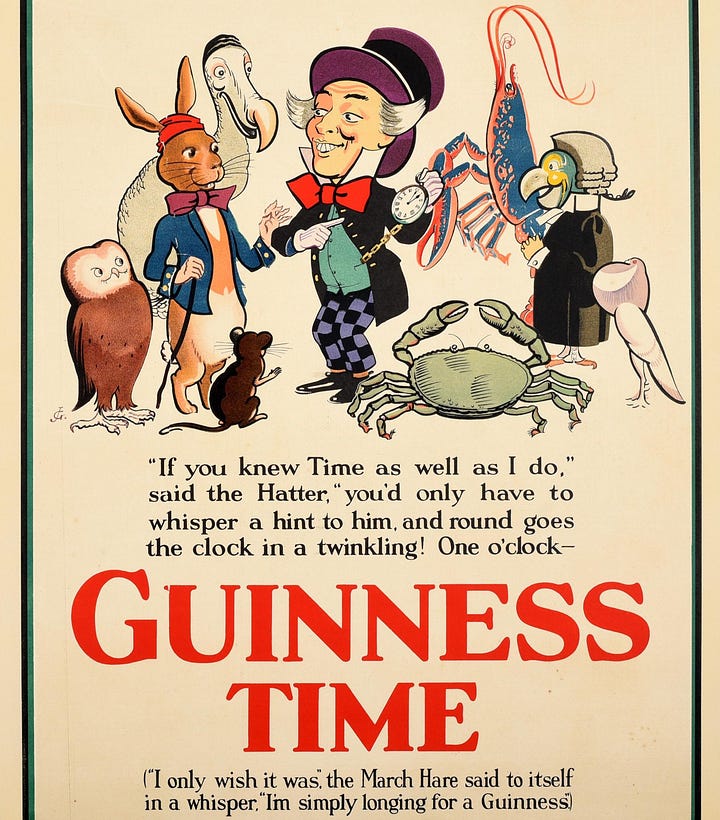

By the time 1960 hits we’ve had 20+ years of Guinness advertising, using parodies of Alice to help create what modern marketers would call brand salience, not least the Festival of Britain clocks that toured the country (and which deserve their own post).2 Guinness Time is the brain-worm of an advertising idea that remains ubiquitous, thanks to giant clocks in public places:

Disney’s 1951 Alice in Wonderland has given the books a new lease of life, and the many fashion influences that accelerated in the 1930s with the popularity of the ‘Alice Band’ also show up in the press with things like this article on Alice-in-Wonderland Party Dresses, from Nov 1959:

And, bringing it closer to home and to the Beatles story, Paul McCartney’s fiancé-to-be — Jane Asher — has made a recording of both Alice books.

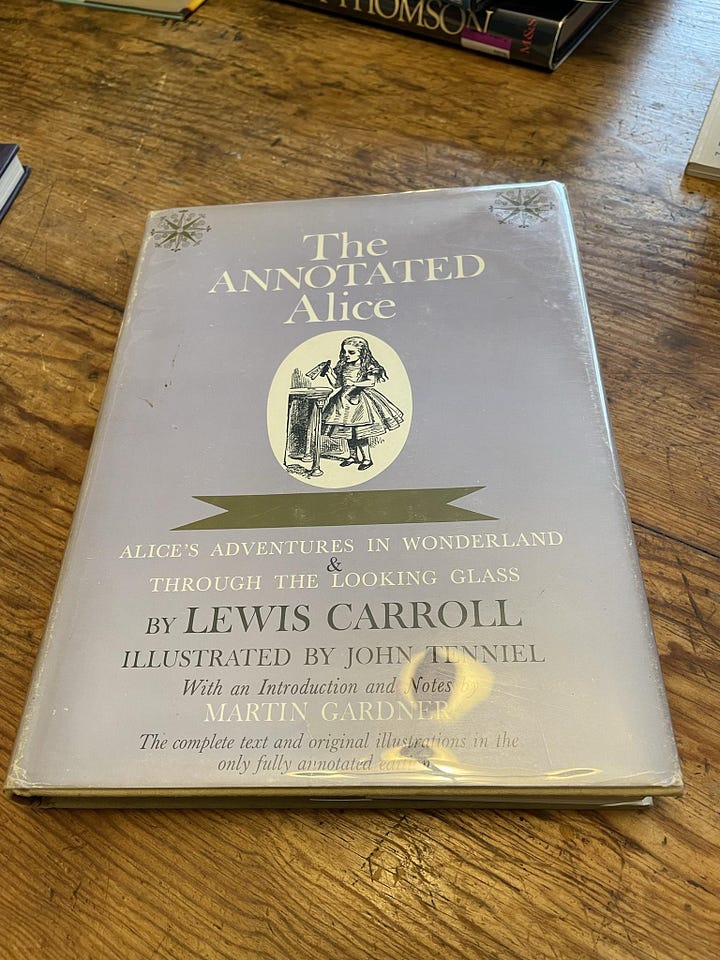

Then as the new decade begins Martin Gardner publishes his The Annotated Alice, sparking a reassessment of the many inbuilt references, sources and meanings that have perhaps escaped the average reader. It will re-appear in the more user-friendly Penguin paperback in 1965, on the 100th anniversary of Alice’s first outing:

So Alice is most certainly a popular, well-known, “intertext, as well as popular book. The story, the characters, are simply part of the DNA of Englishness, something that post-war children grew up reading, or having read to them. Talk about going down a rabbit-hole, “off with their heads”, “curiouser and curiouser”, Mad Hatters, or just plain “Alice”, and everyone understands.

But as the ‘60s progress, with the launch of the pill (as well as consumption of other pills), beat music, and the Beatles, a world turning into colour — with a burgeoning youth movement, anti-establishment attitudes and pop culture — it’s Alice’s subversive, transgressive, side that takes hold.

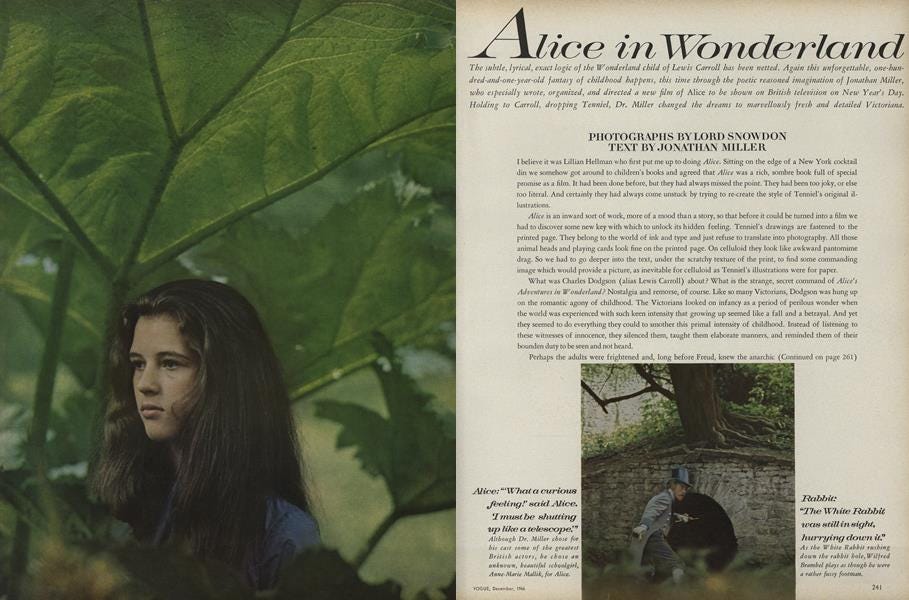

1966 will see a new, lavish, TV adaptation, that — reading the reviews — was largely criticised for its “adult themes”, in a departure from the innocent tale of young girls and dreamy adventures.

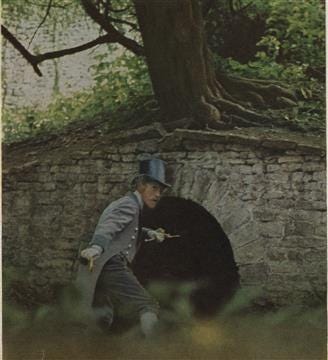

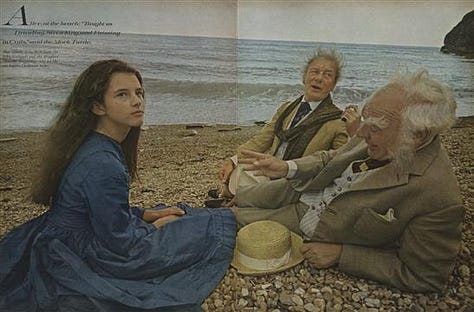

Jonathan Miller’s Alice in Wonderland dials up the psychology of Alice in a world of adults, emphasising the Victorian notion of childhood as simply a formative stage to be passed through on the way to grown-upness.

What are we to make of Alice’s gaze, breaking the cinematic fourth wall? It seems questioning to me, open, curious of course, but also challenging the viewer. Miller calls it “an inward sort of work, more a mood than a story”.

12 million viewers tuned into BBC1 in 1966. It would be shown again in 1967, but it’s also covered in Vogue, in a lavish spread that I think underscores its cultural impact and the seriousness of the interpretation.

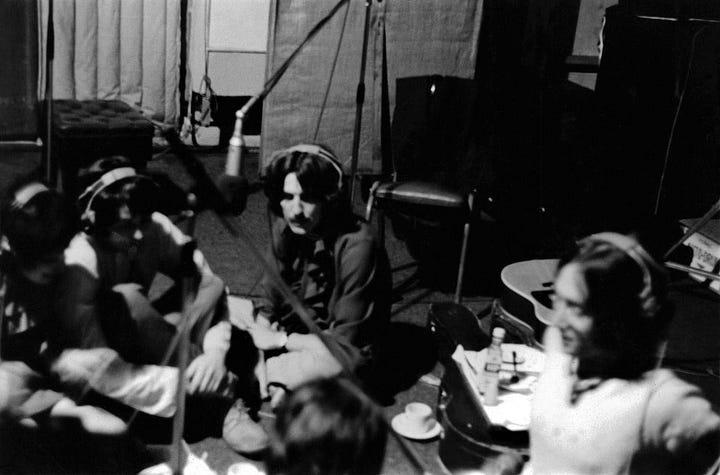

Likewise, sticking setting the action in Victorian England, his choice of Ravi Shankar for the soundtrack, with George Harrison dropping into recording sessions, highlights the Imperial context into which Alice was born (and which I think the choice of Hookah-smoking caterpillar in Carroll’s original echo).

Of course the Ravi Shankar connection delights me as it brings the world of The Beatles and Alice together firmly, and it will only be a matter of months before ‘Within You Without You’ is recorded (March-April ‘67).

From film to fashion

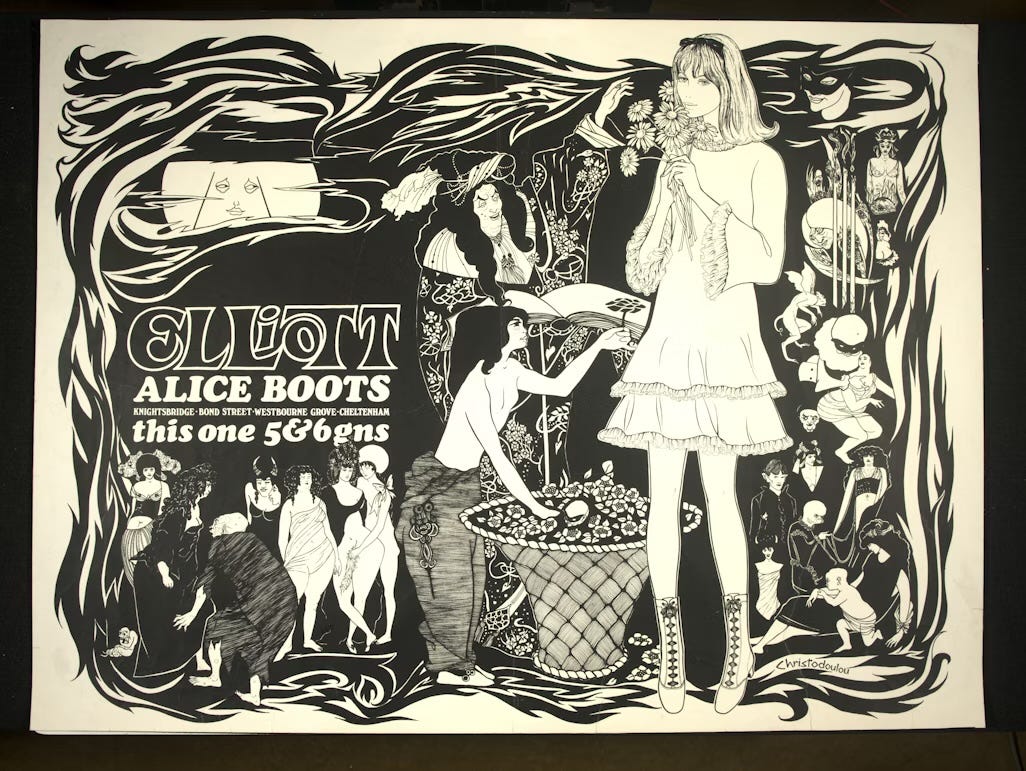

Alice bands were already a popular item of clothing, emerging in the ‘30s, but in mid 1960s we see the emergence of Alice Boots, one of a range of products produced by Elliot’s and illustrated by Paul Christodoulou in a Beardsley-inspired, art nouveau, style.

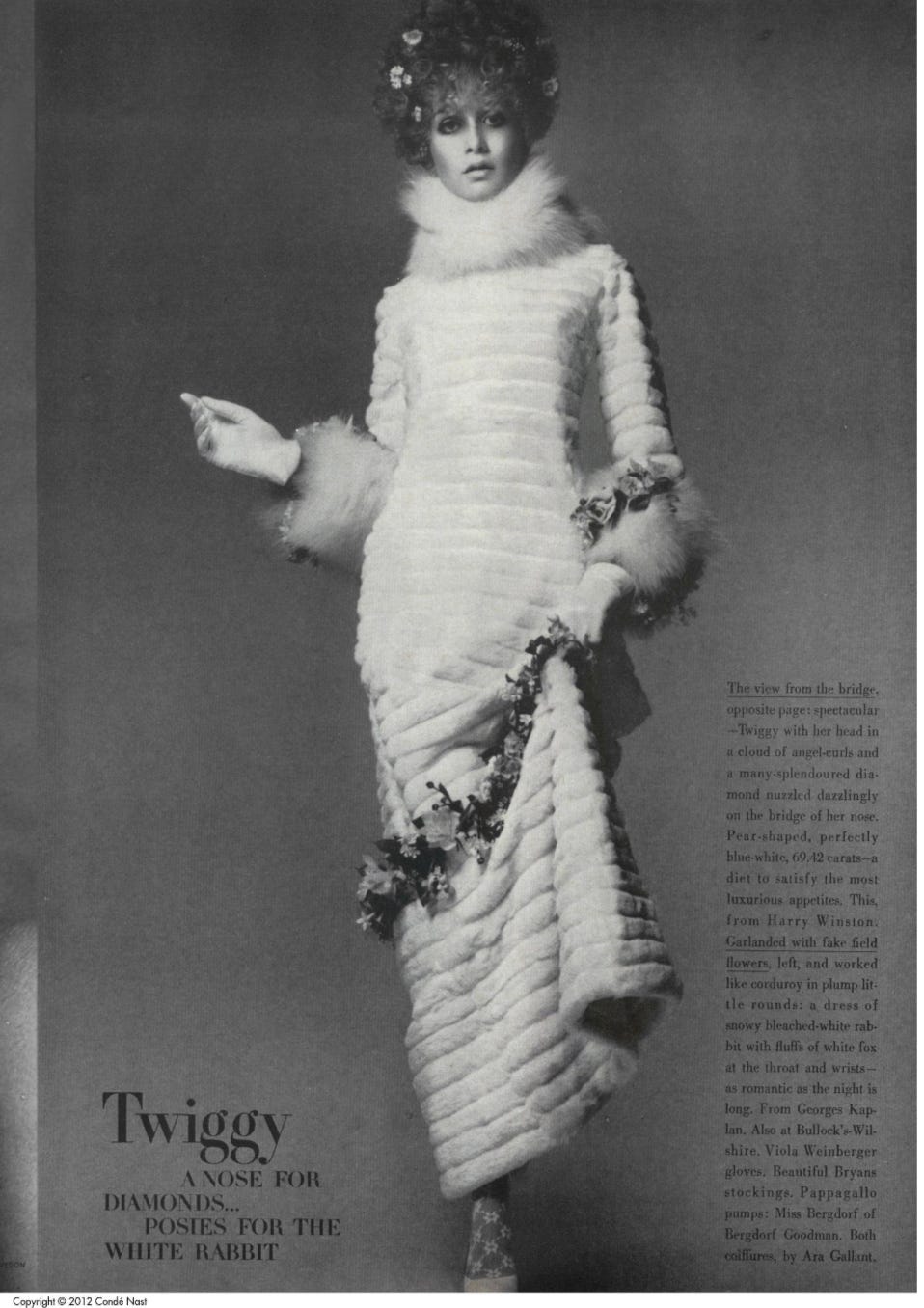

And then a few years later, Twiggy gets involved.

I’m indebted to Kiera Vaclavik — who’s the guest star of next week’s interview special on Alice & The Eggmen — for alerting me to this Richard Avedon shoot for Vogue in 1967. Entitled “posies for the white rabbit”, this features Twiggy sporting a dress made out of white rabbit fur!!

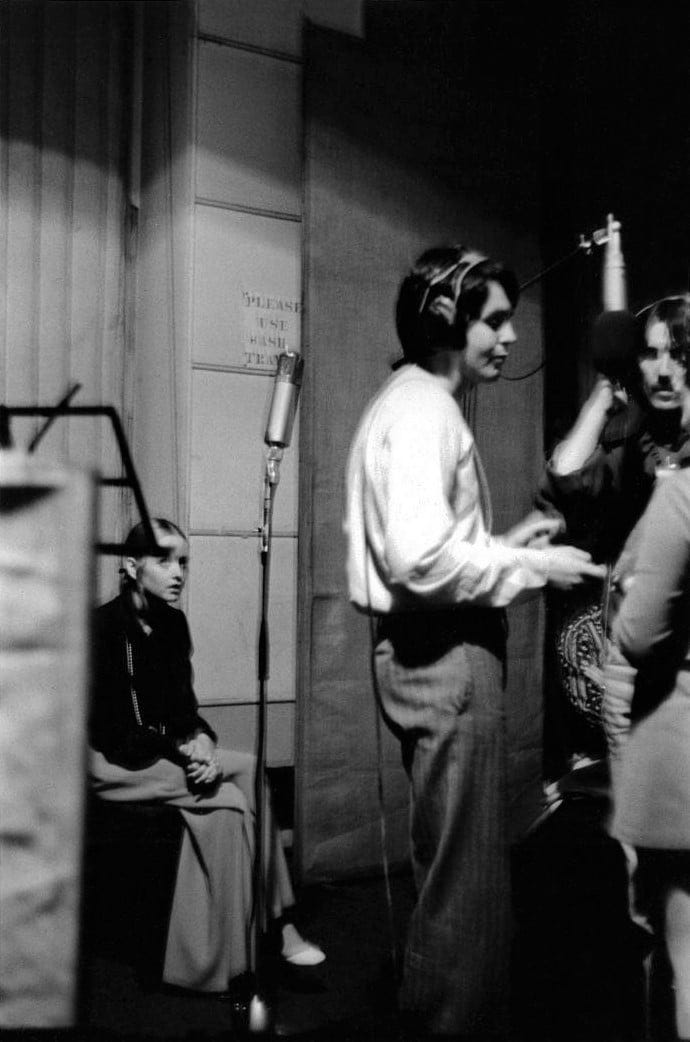

It’s worth noting in passing, just to keep reinforcing how intertwined the 60s London scene was, that Twiggy and McCartney were friends and that she attended recording sessions in 1968, for ‘Revolution 1’.3

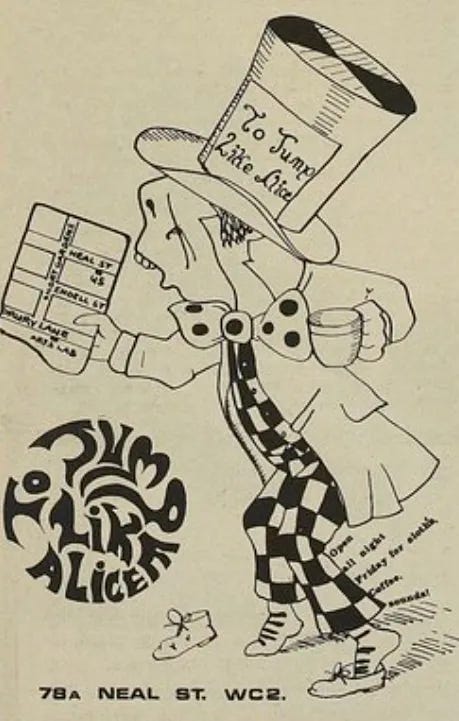

Alice also shows up in more playful ways. In the world of fashion, with the explosion of fashion boutiques catering to the in-crowd — from Mary Quant’s bazaar and other King’s Road staples like ‘Granny Took a Trip’ to Carnaby St — I’ve become really curious about a lesser-known spot called ‘To Jump Like Alice’.

Owned by Sarah Buadpiece and Debbie Torrens, it’s on Neal St, in Covent Garden, and is one of several boutiques popular with the psychedelic youth movement, like the Apple Boutique, Mr Fish, and Tommy Nutter. Here it is:

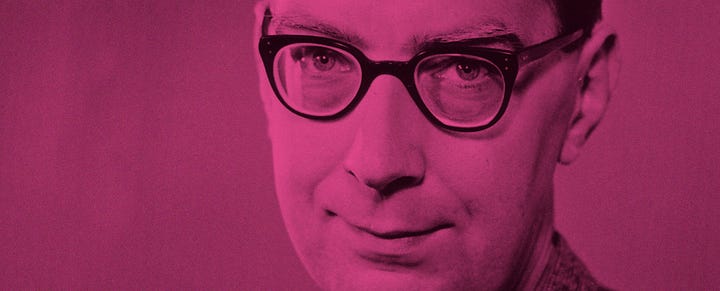

I’m pretty sure the shop took its name from Philip Larkin, the poet:

Here’s the opening of his poem If, my darling

If my darling were once to decide

Not to stop at my eyes,

But to jump, like Alice, with floating skirt into my head-Philip Larkin, If my darling (1950)

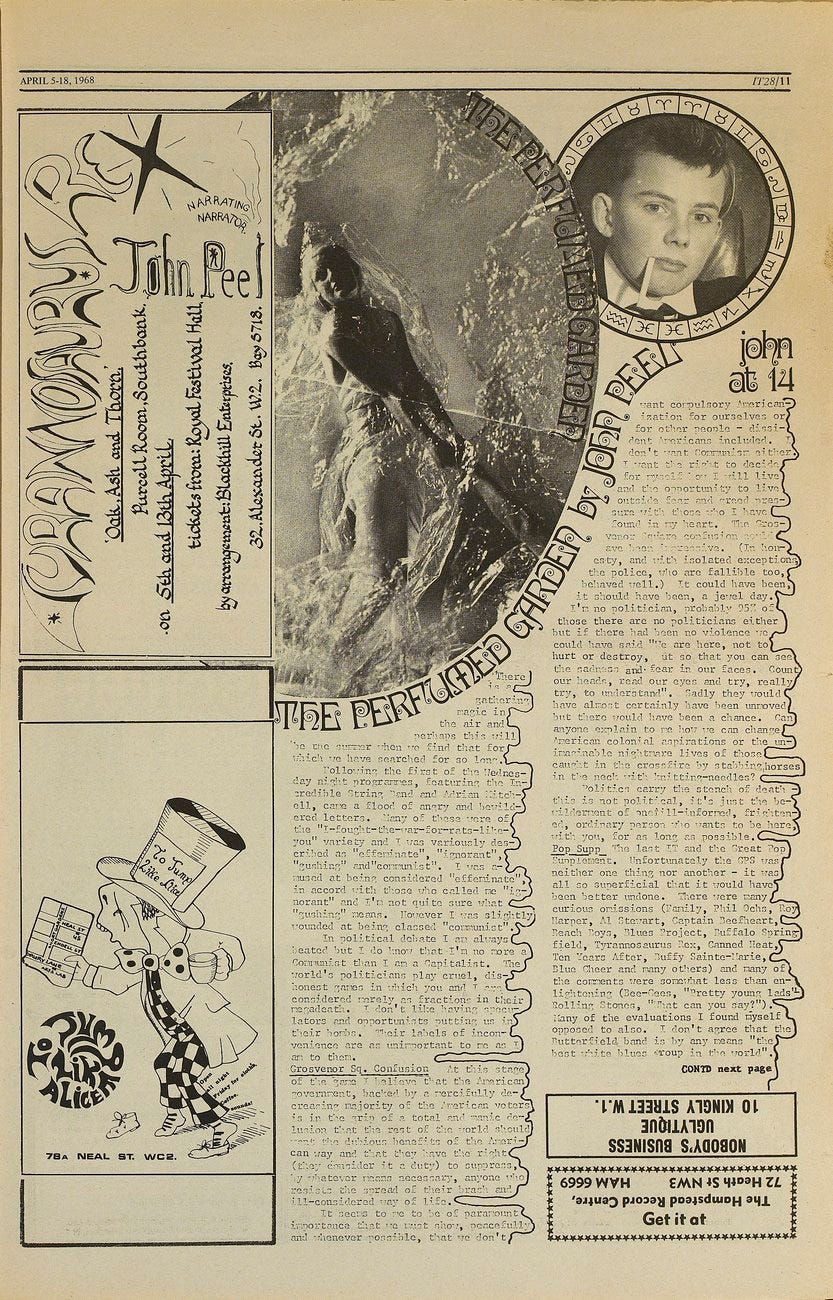

Not there’s not much written about the shop, which is why I was excited, browsing the archives of iconic counter-culture journal The International Times to discover this advert, which also makes clear the debt to Alice.

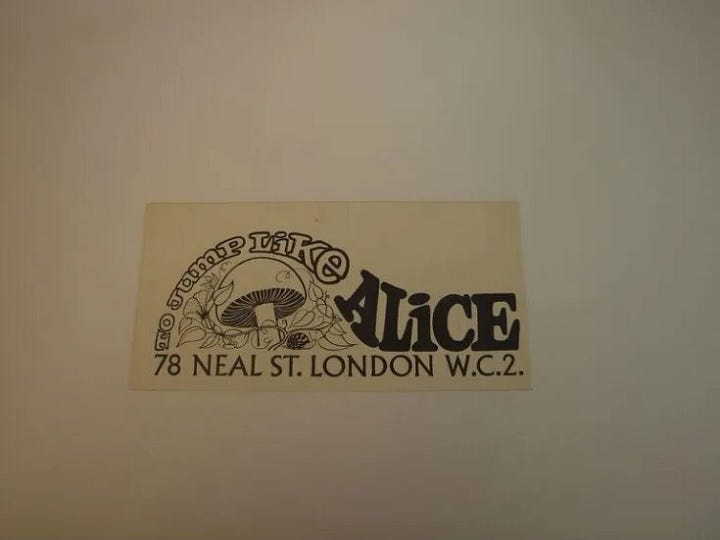

And then, this weekend, I discovered this business card, in the V&A Collections.

Is the Hatter simply an allusion to clothes making? Was it an invitation to “jump like Alice” into a rabbit hole of alternative realities made cloth? Or a riff on the growing role of Alice as counter-culture and drug-culture heroine captured in Jefferson Airplane’s ‘White Rabbit’ the year before its opening? Perhaps we’ll never know.

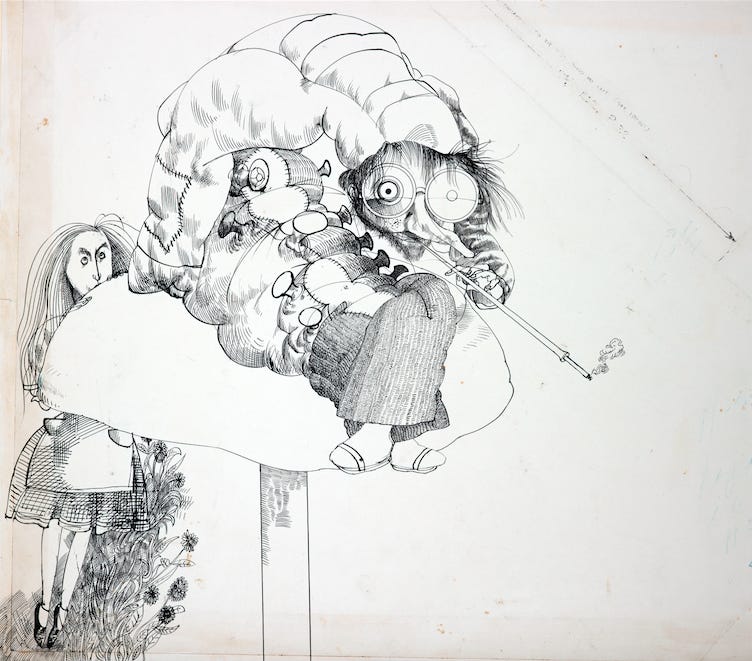

1967 is also the year Ralph Steadman releases his Alice illustrations, bringing a whole new aesthetic and political consciousness to the books.

As his own website says “Steadman updated the classic Tenniel illustrations for the 1960’s turning the White Rabbit into a commuter, perpetually late for work, the Mad Hatter became a union leader and the Caterpillar suddenly began to resemble John Lennon enshrouded in a fog of smoke”.4 Yes, Lennon!

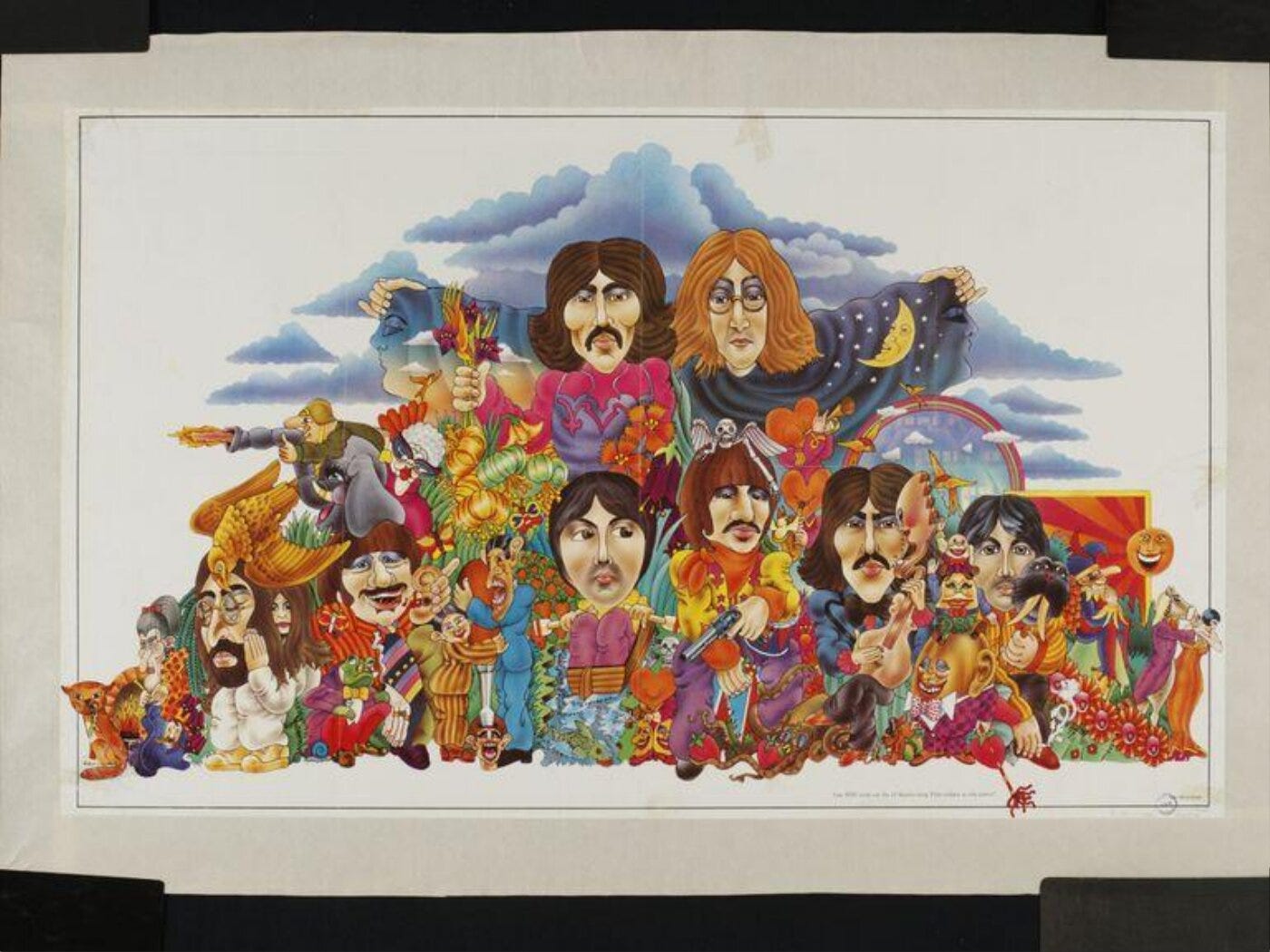

And then we have Alan Aldridge, illustrator of the Beatles Illustrated books, which come out in 1969, featuring spreads like this:

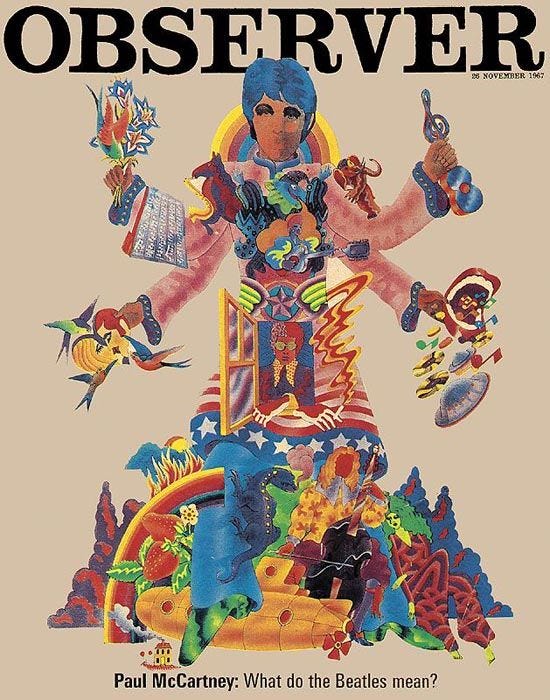

It turns out that — perhaps unsurprisingly — Aldridge is a Tenniel fan. And it’s Aldridge who both interviews Paul for the Observer in November 1967,5 and creates this fantastical cover art. It’s more simply psychedelic than strictly Carrollian, but given his debt to Tenniel — whose approach often combines impossible things — I think we can assume a little nod here, not least because Paul references Alice and ‘Lucy in the Sky’ in the very same interview. QED?

We clearly don’t need to rehash all the other Alicery from The Beatles themselves in these years — even though it’s probably the most visible sign of all — since we’ve already covered ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’, ‘Penny Lane’ & ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’, ‘Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds’, ‘I Am The Walrus’, and the cover of Sgt Pepper, in-depth in previous posts. What we haven’t touched on yet is all the other Alice songs in the same period. And there are a few!

First up Donovan. Most famous for ‘Mellow Yellow’, he also teaches the Beatles how to fingerpick in India in February 1968, influencing songs like ‘Julia’ and ‘Dear Prudence’. And he’d already contributed lyrics for ‘Yellow Submarine’ — “sky of blue and sea of green” — on Revolver, bringing Alice like language to bear:

Children’s songs were easy for me, because I had absorbed so much poetry,” he explained. “My father had read me Robert Louis Stevenson, Alice in Wonderland and an enormous amount of Victorian poems, and so I was well versed in those.

-Donovan, interview.6

Donovan himself wrote some Alice-inspired songs. ‘Under The Greenwood Tree’ (December) quotes the “will you won’t you, will you won’t you, will you join the dance” refrain from the Lobster Quadrille. And, later, in 1971 — on HMS Donovan — we’ll get a ‘Jabberwocky’ and a ‘Walrus and the Carpenter’. Two for one!

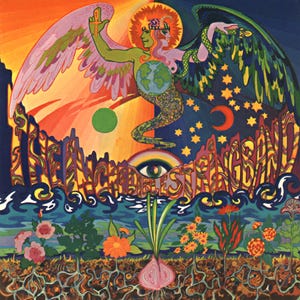

But back in the Summer of this year - that ‘golden Summer’ of 1967, the Incredible String Band release 5000 Spirits or Layers of the Onion, with artwork courtesy of our friends The Fool:

It’s an album much admired by McCartney, who names it his favourite album of 1967, but it’s also in David Bowie’s all-time top 25. Some endorsement. And guess what, it contains the ‘Mad Hatter’s Song’

And if you cried, you know you'd fill a lake with tears,

Still wouldn't turn back the years,

Since the city has took you,

Mad Hatter is on my mind.So sad, sad to see the way it grew

Those other people that I knew

That have either fell or faltered.

Mad Hatter is on my mind.-Incredible String Band, ‘Mad Hatter’s Song’ (1967)

And then there’s another song, from the same vintage — ‘Alice Is A Long Time Gone’ — that was recorded in 1967 (but released only in 1997). Here’s how it opens:

White rabbit smile, white rabbit smile

Cry not so loud my lover frowns

I'm a grown up lady from London town

Yet ever more he sang his sad song-

Sweet Alice is a long time gone

Oh Alice is gone, gone-Incredible String Band, ‘Alice Is A Long Time Gone’, The Chelsea Sessions 1967 (1997)

I’m omitting Alice songs by Frumious Bandersnatch, Berkeley Kites, Tim Hollier, The Formyula, Boeing Duveen and the Beautiful Soup or we’d be here all day.

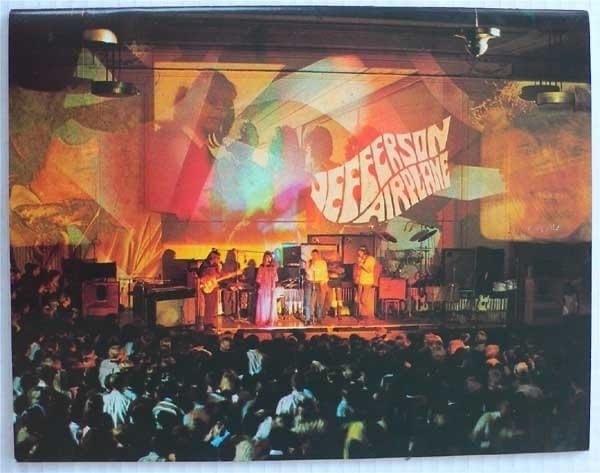

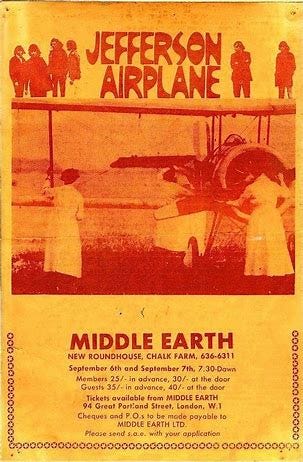

But I can’t leave out Jefferson Airplane, since with their anthem ‘White Rabbit’ from 1967 in the can, they made it over to London to play the amazing Roundhouse in September 1968:

And yes, they opened their set with ‘White Rabbit’.

All this happened in 3 years, or less.

For me it’s just proof that — in what Brian Eno calls the “scenius” — of London fashion, art and culture, Alice was an inevitable and powerful wellspring of inspiration in a way that I suspect is unique in the 150+ year history of the books.

I’m working on fleshing out this timeline so we can visualise it even more clearly and understand the timing and tempo of all of this ‘60s Wonderland.

And see you next time for an interview with the wonderful Kiera Vaclavik, where we’ll be touching on some of these manifestations, and exploring the ‘Alice Look’ down the ages.

Thanks for reading.

Thanks to Catherine Richards for turning me onto this marvellous period in Guinness’ history.